Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Assistant Governor Christopher Kent provided an interesting report on the status of Australia-China trade and investment at the Australian Renminbi Forum in Melbourne on 12 June. The forum was organised by the Australian Renminbi Working Group, an industry body which promotes trade in local currencies between Australia and China.

With the relaxation of capital controls governing Chinese financial market inflows and outflows over the last decade, nations including Australia have been conscious of the vast ocean of Chinese capital becoming available to the world. The volume of bank deposits and investments of Chinese savers alone is around US$20 trillion, having doubled in the last five years.

Recognising that China would be a key growth engine for the world and a crucial source of funds for our banking system, which is structured to be dependent upon foreign capital, Australia collaborated with China to begin to trade in the Chinese currency, the renminbi, seeing China’s financial reform as a commercial opportunity. “[T]he rise of the renminbi presents [a] major strategic opportunity for Australia”, stated chair of the Renminbi Working Group David Olsson in 2014. Olsson has linked the renminbi project with cooperation on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but the latter has not yet materialised.

The backdrop for this project is the UK’s deft economic rebalancing act after the 2008 global financial crisis, moving to dominate the growing renminbi trade in an effort to maintain City of London financial control over global financial markets (“The City of London’s China pivot”, AAS, 11 July 2018). Today it is the largest offshore renminbi trading centre outside of Hong Kong. The UK has urged Australia to help it capture the immense flows associated with Asian growth (“HSBC minister pushes Trojan Horse trade agreement”, AAS, 10 Oct. 2018). A long-term British ambition for Australia is to turn Sydney into a major financial centre in the region, an “Antipodean Venice” or “Wall Street of the South”1 , but the cynical British approach of positioning for financial control while manipulating geopolitical tensions, rather than sincerely developing a mutually beneficial and respectful trade relationship, is doomed to fail in the long term. Australia must decide what is more important: its indispensable trading partner or its “dangerous” Anglo-American ally.

Today’s anti-China environment fosters the manipulative Anglo-American approach, but the reality is our trade and investment partnership has flourished despite all the rhetoric.

To facilitate trade and investment, Australia has had reciprocal currency swap lines with China since 2012; direct trading between the renminbi and Australian dollar since 2013, allowing direct exchange between the two currencies without using a reserve currency as intermediary; an agreement allowing Australian financial institutes to invest in Chinese securities; and an official renminbi clearing house at the Bank of China (Sydney), launched in 2015 following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding at the Brisbane G20 summit in November 2014.

Apart from the growth in trade—with nearly one-third of our exports now going to China and some one-fifth of our imports coming from there—China’s opening capital account “has encouraged deeper financial links between Australia and China”, said the RBA’s Kent, adding that there is further scope to deepen links. There has been a steady rise in bilateral investment and in use of the renminbi by Australian businesses, he observed.

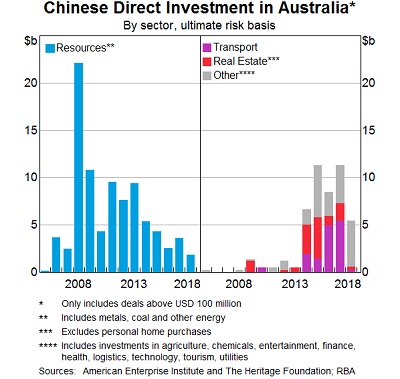

China’s financial opening up saw more investment flowing out of China and across the world, but especially into Australia given the mining boom prompted by Chinese development, which expanded with China’s post-2008 effort to transform its economy. “Chinese investment played a role in expanding Australia’s capacity to meet growing demand for these commodities”, stated Kent. Total Chinese investment in Australia is therefore some eight times larger than a decade ago, although, points out Kent, “this is from a low base and still represents only about 2 per cent of the total stock of foreign investment in Australia”. (Graph 1.)

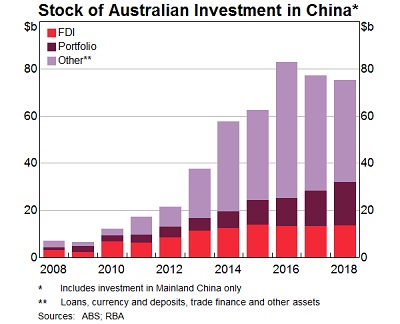

Australian investment in China has grown on a par with Chinese investment here. Four per cent of our GDP is invested there, more if Hong Kong is included. According to Kent, this mainly takes the form of purchases of Chinese bonds and equities, and an increase in loans and deposits of Australian banks in China. (Graph 2.)

As the mining boom slowed, Chinese investments in Australia such as real estate became more prominent, but the flow was dampened when China placed restrictions on non-productive foreign investments in 2017. (Graph 3.)

Chinese banks have also expanded operations here, lending more to Australian business, providing 3.6 per cent of total business credit. With the increasing share of trade invoiced in renminbi—some 3 per cent in 2017—a local pool of deposits worth around $8 billion has built up. The RBA now holds some 5 per cent of its foreign exchange reserve in renminbi assets. Kent concluded that this expanding financial integration would continue to develop, providing new opportunities for both Australian and Chinese business.

Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute Prof. James Laurenceson wrote on 4 July that last year more than a third of Australia’s trade growth came from the relationship with China. Despite a slow-down in Chinese imports of Australian coal, May year-to-date figures show totals are only down by 3 per cent. Total two-way trade with China grew by $10 billion from January to May 2019, he reported. “When the politics between Australia and China get rough, it is the economic relationship that provides the ballast. That’s reason to celebrate, not panic.”

1. David Love, Unfinished Business: Paul Keating’s interrupted revolution (Melbourne: Scribe Publications, 2009).

Australian Alert Service 10 July 2019