Given increasing moves towards secrecy and suppression in the name of national security, the question which looms larger by the day is, what is the Australian government hiding? Clues are provided by the types of people the government is working overtime to silence: a journalist exposing the expansion of domestic surveillance powers under the guise of national security; a former serviceman alleging war crimes by Australian troops overseas; an Australian Secret Intelligence Service officer revealing that Australia bugged a rival cabinet during a lucrative treaty negotiation; an Australian Tax Office employee sacked after exposing secret accessing and garnishing of private bank accounts.

Whistleblowers are “the canary in the coal mine” of democracy, US National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Thomas Drake told the ABC on 8 October. “There’s now a culture of fear about speaking up”, Dr Suelette Dreyfus of Melbourne University warned.

The two were reacting to the fact that they were axed from the program of speakers addressing the Australian Cyber Conference 2019 on 7-9 October in Melbourne. The conference was organised by the Australian Information Security Association and backed by the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), the body recently created by Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton to coordinate Australia’s cybersecurity. Based at the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), the agency for overseas electronic spying, it was this new cyber centre that demanded the conference drop the speakers. The conference was about raising awareness of cybersecurity issues; among its sponsors were members of the Anglo-American military-industrial complex BAE Systems and Thales.

Drake has exposed US mass-surveillance programs and 9/11 intelligence failures, while Dreyfus was to tell the conference about safe digital dropboxes for anticorruption whistleblowing. Drake was only notified shortly before his flight to Australia that his address had been cancelled. He said this had never happened to him before, calling it “a most alarming and Orwellian development and a distinct form of brazen censorship”.

In a 23 October Senate Estimates hearing on foreign affairs, defence and trade legislation, ACSC head Rachel Noble said it was she who’d made the decision to can the pair. The two were to appear on a panel with Edward Snowden via video hookup, Noble claimed. Drake had no knowledge of this, however, saying the idea was concocted as a foil. Snowden and Drake, Noble said, have a reputation as “known public advocates for unauthorised disclosure or the leaking of classified information outside of legitimate whistleblowing or lawful whistleblowing schemes”. Their views, she said, “are inconsistent with Australian government laws and our processes and values”. Noble previously worked in the Home Affairs and Defence Departments and was Deputy Chief at Pine Gap.

Writing afterwards for RootsAction.org, Drake slammed Australia’s public interest disclosure laws—the legal process for public servants to blow the whistle—as “a conflicted patchwork with huge carve-outs for national security and immigration”, affording little protection. “What is happening in Australia is most concerning to me as fundamental democratic values and principles are increasingly under direct attack around the world from the rise of increasing autocratic tendencies and raw executive authorities bypassing, ignoring and even undermining the rule of law under the exception of national security and government fiat. ... The trend lines of increased secrecy around the world by governments does not bode well for societies at large. History is not kind.”

Witness J

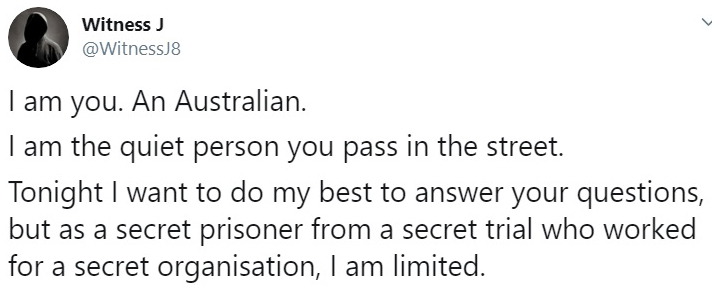

As if to prove the point, a new case is emerging , albeit shrouded in secrecy. According to an ABC investigation, a former military intelligence officer with a distinguished record, dubbed Witness J, was tried and sentenced in complete secrecy. Only 13 words were recorded publicly regarding the trial: “Before Justice Burns, in Court Room SC4, at 10:00 AM. Sentence: Matter Suppressed.” Even that would not have been known if ABC and Canberra Times journalists had not made inquiries after seeing security guards barring a Canberra courtroom.

Convicted in 2018 for mishandling classified information under national security laws that allow suppression of proceedings, Witness J was sentenced to two years and seven months’ imprisonment. He was released in August.

Witness J had served in East Timor, Afghanistan and Iraq. While undergoing a routine security re-validation, concerns were raised that he might be compromised, and an investigation ensued. He sought mental health support on three occasions, which wasn’t forthcoming, and couldn’t seek outside help due to his security clearance. According to the ABC, in the course of making an internal complaint “to the head of security and a departmental psychologist back in Australia”, his communications used “unsecure electronic means”—the basis for the eventual charge against him. He was accused of breaching secrecy provisions, imperilling lives and national security; but a source cited by ABC said “Witness J had to be ‘shut down’.” Witness J argued there was no information disclosed as a result of his actions, but pleaded guilty on the advice of his lawyer.

When the Canberra Times inquired about the case, Justice John Burns replied he had closed the court according to “consent orders” under the National Security (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004. Attorney-General Christian Porter told the ABC: “The court determined, consistent with the Government submission, that it was contrary to the public interest that the information be disclosed and the information was of a kind that could endanger the lives or safety of others.”

Former Supreme Court judge John Dowd called for the circumstances of the secret trial to be explained, reported the ABC. Barrister Bret Walker, formerly an independent national security legislation monitor, said, “It’s not good enough for the public to be told ‘it’s in your interests that you are not told’.”

These developments have emerged as Prime Minister Scott Morrison launched the Counter Foreign Interference Taskforce, an elite intelligence taskforce led by ASIO, involving all Australian spy agencies and the Australian Federal Police, to share and pool classified information. Described as the mechanism to enforce the foreign interference laws passed in 2018, at a cost of $88 million the new agency will take the threat to freedom of speech and association represented by those laws a step further with enhanced spying capabilities. It has even been suggested that all new MPs be subjected to security screening, something which would allow spy agencies to vet incoming leaders and exclude those who might challenge them.

Additionally, despite long delays in the Freedom of Information process, Home Affairs boss Michael Pezzullo has announced he will not seek further resources for the sector.

Australian Alert Service, 11 December 2019