This article was originally published in 2013 and has been reproduced here for its highly relevant historical content.

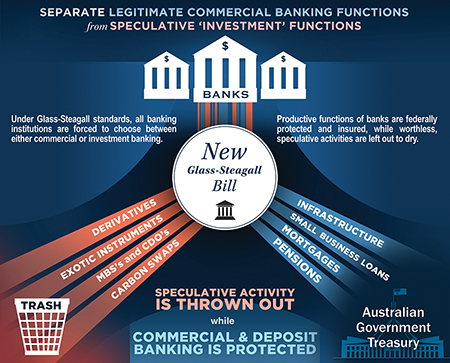

The US Congress is now considering a bill, House Resolution 129, to re-enact the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which split commercial banks that hold deposits off from risky investment banks.

The Glass-Steagall Act protected America’s depositors until its repeal in 1999 led directly to the Wall Street megabanks, their reckless gambling losses that caused the global financial crisis, and the trillions of dollars in government and central bank bailouts.

Politicians in Italy, Iceland, Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland are working on Glass-Steagall laws; and more than 60 per cent of British MPs support a full-scale Glass-Steagall-style separation for the UK.

Australian politicians must recognise that the financial danger their international counterparts are acting to avert is a global threat from which Australia is not immune, and move urgently to enact a Glass-Steagall separation for the Australian financial system.

By the Glass-Steagall standard, Australia’s banks are a nightmare.

Four major banks—CBA, ANZ, NAB and Westpac—dominate Australia’s financial system. The same banks dominate New Zealand. The IMF noted with concern in November 2012 that the level to which the domestic financial system is concentrated in these four banks, which between them hold 80 per cent of Australian residents’ assets, makes them systemic—a crisis in these banks is a crisis for the entire system.

The big four banks are each conglomerates, combining the traditional banking of deposits and loans with the riskier financial activities of investment banking, funds management, stockbroking, and insurance. This structure is precisely what the architects of the Glass-Steagall Act recognised posed such a risk to the security of depositors.

There is an assumption that the big four won’t get into crisis, as they are the strongest banks in the world. This is the same assumption that every nation presently in financial crisis held about their own banks when they were riding high. Not only was it proved wrong for those nations, it has already been proven wrong for Australia. The supposedly “sound” Australian banks almost went bankrupt when the GFC erupted in Sep.-Oct. 2008, unable to repay their enormous foreign debts, and had to beg the Rudd government to go guarantor for new foreign borrowings to roll over their existing loans. The banks told Rudd that without the government guarantee “they would be insolvent sooner rather than later”, recounted Ross Garnaut and David Llewellyn-Smith in their book The Great Crash of 2008. They are still teetering on the edge. From its recent analysis of the Australian financial system, the IMF expressed concern that Australia’s banks have only six per cent capital. This enables the banks to rack up bigger profits, but it leaves them extremely vulnerable—just a six per cent decline in the value of their assets will wipe them out.

Adding to the structural vulnerability, the four banks are very similar businesses:

Adding to the structural vulnerability, the four banks are very similar businesses:

- They are each heavily exposed to the inflated domestic property market, which accounts for more than 50 per cent of their lending. A property market decline in Australia similar to that suffered in every other economy whose property bubbles burst would be enough to collapse all four banks.

- Each bank is dangerously exposed to toxic derivatives contracts, with a notional value many times their assets. The Reserve Bank reports total derivatives exposure for all Australian banks is a fraction short of $20 trillion; total bank assets by comparison are $2.85 trillion. This exposure is kept “off-balance sheet”. In August 2012, when former Citigroup Chairman and CEO Sandy Weill told CNBC television that Glass-Steagall should be restored, he added, mindful of the destruction that derivatives had wreaked on Wall Street in 2008, “There should be no such thing as off-balance sheet.”

- The four banks are also heavily reliant on foreign loans. More than half, $802 billion as of Sep. 2012, of Australia’s gross foreign debt is owed by banks, the majority of that by the big four. $513 billion is short-term debt, one year or less maturity; $340 billion is 90 days or less. It is this short-term debt which virtually bankrupted them in 2008.

Australians call for Glass-Steagall

A number of Australians with intimate knowledge of the Australian financial system have called for Glass-Steagall. The most prominent is former NAB CEO and BHP Chairman Don Argus. Argus told the 17 Sep. 2011 The Australian, “People are lashing out and creating all sorts of regulation, but the issue is whether they’re creating the right regulation. What has to be done is to separate commercial banking from investment banking. I challenge any commercial bank board to really understand investment banking risk. It’s different and needs to be properly priced. But you actually don’t want it on a commercial bank balance sheet that comprises depositor funds.”

The 6 Aug. 2012 Australian Financial Review reported an unnamed “retired senior local banker” who was raising “concerns about the potential for a local bank to get into strife”. Under the headline “Big four might make a better eight”, the AFR revealed that their source, careful to remain anonymous due to his present position, echoed Wall Street banker Sandy Weill’s call for Glass-Steagall: “Australia’s banks were too big and complex and should be broken up”.

Background: the decline and fall of the Australian banking system

Australia has never had a Glass-Steagall-style banking separation, but the domestic banking system was not always exposed to the level of risk as it is today.

Commonwealth Bank

When the government-owned Commonwealth Bank exercised full regulatory control over the banking system from 1911-1959, the banking system was tightly regulated and very safe. Prior to the Commonwealth Bank, banking had been very volatile. For instance, 20 of 22 Australian banks had been wiped out in the 1892 economic crisis. From its commencement in 1911, the Commonwealth Bank immediately strengthened the banking system, and was able to stop a run on the private banks during World War I by announcing it stood behind their deposits. No Australian banks failed during the Great Depression, compared to the 4,000 American banks that closed between 1929 and the 1933 passage of the Glass-Steagall Act. Labor leaders John Curtin and Ben Chifley gave the Commonwealth Bank even greater powers over the private banks during and after WWII. The Commonwealth Bank regulated what the private banks could charge for loans and pay for deposits, and the extent, and nature, of bank lending. The private banks complained about the regulations, but they were still profitable.1 It was under Chifley’s successor, Liberal Party Prime Minister Robert Menzies, when cracks first appeared in the banking system. Menzies’ personal sponsor in politics was the Melbourne financier Staniforth Ricketson of the JB Were stockbroking firm; moreover, his Liberal Party was staunchly the party of the private bankers. In 1959 Menzies stripped the Commonwealth Bank of its regulatory powers over the private banks, and vested those powers in a new central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Finance companies

Even before that, the banks had started straying outside their previously disciplined standards. In the 1950s, paralleling a consumer credit bubble expansion in the US, finance companies sprang up in Australia to fund hire purchase of cars and consumer goods, such as fridges and mixers. Although the banks didn’t engage in hire purchase, between 1953 and 1957 every major bank acquired a stake in a finance company: the Bank of NSW, now Westpac, had Australian Guarantee Corporation (AGC); ANZ had Industrial Acceptance Corporation (IAC); the National had Custom Credit; the Commercial Bank of Australia had General Credits; ES&A had Esanda; the Commercial Banking Company (CBC) had Commercial and General Acceptance (CAGA); the Bank of Adelaide had Finance Corporation of Australia (FCA).2 In the 1960s, the finance companies moved heavily into property speculation, exposing the depositors in their stakeholder banks to new risks. This speculation included financing the first deals of some of Australia’s most notorious corporate cowboys, including Alan Bond and John Elliott. The Bank of Adelaide’s FCA financed Alan Bond’s first land deal in 1960; the CBC’s CAGA helped Bond make his first million in 1967. General Credits financed John Elliott’s takeover of Tasmanian jam maker Henry Jones IXL in 1972, even though Henry Jones was a client of its parent bank CBA. When property prices collapsed in the mid-1970s, the big losses suffered by the finance companies blew back on their associated banks. When FCA collapsed, its stakeholder the Bank of Adelaide was only saved by the Reserve Bank ordering ANZ to take it over.

Investment banks

To cash in on the 1960s property and mining speculation booms, new investment banks also began competing for business. Known as merchant banks, they were usually joint ventures between different foreign banks, or foreign banks and local institutions. They were also associated with the corporate raiders. Martin Corporation which was formed in Sydney in 1966 by a consortium of foreign banks including Baring Brothers, the Chartered Bank and Wells Fargo, bit the dust within a few years but not before it gave 1980s high-flyer Laurie Connell his first start. In 1974, Australian life insurer National Mutual teamed with the Bank of New York to form an investment bank named Citinational Holdings. In 1975 Citinational financed the first takeover of one Christopher Skase. Citinational’s chairman was Keith, later Sir Keith, Campbell, who four years later was tapped by then Treasurer John Howard to head the seminal Financial System Inquiry that designed the Hawke-Keating economic reforms.

There were some restrictions on how much banks could own of investment banks, but no blanket ban. In 1980 the law was changed to lift the restriction on the percentage stake banks could have in investment banks from 33 per cent to 60 per cent.

Bank deregulation

The private banks decried the regulations they had to abide by, especially during the years the Commonwealth Bank was in charge, but the regulations were based on an important principle—the common good. “Old” Labor’s champions of national banking, Commonwealth Bank founder King O’Malley, Frank Anstey, Ted Theodore, John Curtin and Ben Chifley, believed that the financial system must serve the needs of the people. To do that, the banking system had to be structured to ensure that credit was available for the government to build infrastructure and invest in national economic development, and for essential primary and secondary industries, the productivity of which generated the tangible wealth that underpinned the living standard of the population. Banking controls minimised the ability of the private banks to speculate, and encouraged investments in the production of physical infrastructure, goods and essential services.

The global financial system changed dramatically on 15 August 1971, when US President Richard Nixon ended the Bretton Woods system of fixing the US dollar to gold. This decision initiated a global push for financial deregulation, masterminded in the powerful banking houses of the City of London. Global deregulation represented a new wave of British imperialism, but in the British Empire’s new form, not as a territorial empire, but as an “informal financial empire”.3 In late 1971 City of London scion Lord Jacob Rothschild formed a cartel of predatory banks called the Inter-Alpha Group to steamroll through nation after nation as they deregulated their economies, plundering wealth through previously-illegal methods of financial speculation. Deregulation cast aside the rules that ensured the health of the physical economy, unleashing banks to exploit new and exciting and risky ways to make money... from money.

In Australia, the early post-Bretton Woods years in the 1970s saw a flood of merchant/investment banks established, usually as subsidiaries of foreign parent-banks which were aggressively expanding in the increasingly deregulated world. The Australian financial system wasn’t yet deregulated, but regulatory loopholes were already being exploited, as seen above in the case of banks owning finance companies.

The Millionaire’s factory

Enter Hill Samuel Ltd., now Macquarie Bank, aka the “Millionaire’s factory”. In 1971 three young up-and-comers from Sydney-based merchant bank Darling and Co., a subsidiary of the powerful City of London bank Schroder’s run by Australian financial wunderkind and future World Bank chief James Wolfensohn, took over the two year old Australian subsidiary of another powerful City bank, Hill Samuel. Backed by a London parent bank closely tied into the highest levels of the British establishment, including British intelligence, David Clarke, Mark Johnson and Tony Berg ran an investment banking operation that engaged in takeovers and other activities similar to all merchant banks, but which also pioneered ways to tap into and siphon off profits from money that flowed between various sectors of the financial system. The financial schemes that Hill Samuel pioneered were not illegal. However, nor were they in any way productive for Australia’s physical economy. They were money-shuffling arbitrage schemes, devised to lure funds that would otherwise be bank deposits, or in superannuation and life accounts, into speculating on differences in the price of money, i.e. interest rates.

Two examples: Hill Samuel’s breakthrough scheme was an idea put to David Clarke by Melbourne financier Keith Halkerston, to exploit the gap between what banks paid their depositors in interest, and what those banks earned in interest by investing the depositors’ money in gilt-edged securities such as Commonwealth Treasury notes and bank-guaranteed commercial bills. In the turbulent 1970s, returns on these securities could go above 20 per cent, whereas government regulations kept deposit interest rates low. The market for these securities was open only to large operators, because the minimum buy-in was well above the capacity of most individual investors. Hill Samuel set up a trust, the Hill Samuel Cash Management Trust, in which individual depositors seeking higher returns could pool their funds for Hill Samuel to invest in the gilt-edged securities. The trust then paid out to its members returns almost as high as the professional money market, and much higher than deposit rates, and Hill Samuel was able to skim off the top. The trust was a runaway success, attracting $100 million in four months, and soon grew to $1 billion and kept growing.

Inspired by this success, Hill Samuel identified a similar opportunity in an early form of what we now call mortgage securitisation. To exploit the difference in interest between what banks paid for deposits and what they earned by lending those deposits as mortgages, Hill Samuel teamed up with John Symonds, now famous as the founder of Aussie Home Loans—“At Aussie, we’ll save you.” Hill Samuel fronted Symonds money to make home loans marginally cheaper than the banks. Symonds delivered the mortgages to Hill Samuel, which insured each mortgage with the Commonwealth government’s Home Loans Insurance Corporation. Insuring them with the government in this way effectively turned the mortgages into gilt-edged securities, and Hill Samuel on-sold them in bundles of 1000 to superannuation funds and life offices, again skimming a margin of interest off the top for itself.

Campbell Report

With this experience in exploiting Australia’s existing financial structure, Hill Samuel was ready to spearhead the Australian front in the City of London’s global deregulation offensive. In the late 1970s, future Liberal Party leader John Hewson returned to Australia from working for the International Monetary Fund in the US to work two jobs: as chief economics adviser to then Treasurer John Howard, and as a consultant to Hill Samuel. Hewson convinced Howard to establish an official inquiry into the Australian financial system, with a view to deregulation. To chair the inquiry, Howard appointed investment banker Sir Keith Campbell—Christopher Skase’s original backer. Another member of the inquiry was the schemer behind Hill Samuel’s cash trust, Keith Halkerston. Entirely predictably, in its formal recommendations in 1981, the Financial System Inquiry, aka the Campbell Report, demanded full deregulation of the Australian financial system. Chairman Sir Keith Campbell insisted his reorms would make the Australian financial system more “efficient”—efficient for Hill Samuel and the corporate cowboys such as Christopher Skase, Alan Bond, Laurie Connell and John Elliott to extract quick profits at the expense of the long-term health of the physical economy.

The Campbell Report targeted for destruction every financial regulation that served to direct investment into long-term productive processes. It demanded:

- the abolition of government controls over the nature of bank lending, by which the government instructed the banks to give preference to farmers, small business and home-buyers;

- the sale of all of the government-owned financial institutions that existed to provide cheaper finance to farms and small businesses—the Australian Industry Development Corporation, the Primary Industry Bank of Australia, the Commonwealth Development Bank, and the Housing Loans Insurance Corporation;

- the abolition of the “30/20 Rule” and other ratios which obliged the savings banks, trading banks, life offices and superannuation funds to invest a fixed percentage of their assets in government bonds—this requirement provided security for the financial institution, and ensured the government could borrow readily.

Campbell’s list of demands also included the removal of government controls over all interest rates charged by banks; the abolition of government controls over the amount of lending by banks; the lifting of all controls over capital flows in and out of Australia and the floating of the dollar; and the admission of foreign banks into Australia.

Next came a political charade that deserved to star in the movie The Sting. Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, who had some protectionist inklings, did not wholeheartedly embrace the Campbell Report. Treasurer Howard was only able to get one of the Campbell Report’s recommendations, to let in foreign banks, adopted as official policy, but not in time to be implemented before the Bob Hawke-led ALP won the 1983 election. However, that didn’t matter, because, in an epic betrayal of 90 years of the Australian Labor Party’s history of fighting for the common good against the private Money Power, Hawke and his Treasurer, Paul Keating, took office fully intending to implement the Campbell Report. But first they had to re-brand it, to fool their constituents by giving it the appearance of a Labor initiative. They announced the Martin Inquiry by Victor Martin to “review” the Campbell Report, but in fact to rubber-stamp it. To make the charade more convincing, Keating adopted the aggressive tone of his claimed mentor Jack Lang, panning the management of Australia’s banks as smug fat cats, protected by regulation from real competition. It was a fraud, of course: Keating’s banking deregulation may have meant some discomfort in some individual financial institutions, but it was a boon for the private financial sector as a whole, permanently increasing its power over the economy, and over government. Keating mimicked Lang’s tone, but he trashed his legacy.

Hill Samuel was omnipresent as Keating stripped away Australia’s banking regulations. Its currency traders effectively managed the first major act of deregulation, the December 1983 float of the Australian dollar. Unabashed Keating fan David Love indicated in a 17 Feb. 2011 column in The Age entitled “The Aussie float—a love story” that Keating seemingly had pre-planned the float with Hill Samuel. “Keating knew that, should the $A float, there would be there waiting for it a highly professional international trading home and that this could be counted on as a factor for stability in a float,” Love revealed; “The $A traded in the Hill Samuel basket from the day it floated in 1983.” When Keating handed out banking licences to foreign banks in 1985, Hill Samuel was first in line, and became Macquarie Bank, with Campbell Report architect John Hewson now as executive director. Macquarie Bank went on to play a central role in Keating’s flagship superannuation reforms, to force workers to hand over a percentage of their wages to Macquarie Bank and other fund managers. This would create a massive pool of privately-managed funds to invest in privatised infrastructure, toll roads and the like, which Keating fantasised would turn Australia into a global financial centre, “the Wall Street of the south”.

Wallis Committee

In 1996 the newly elected Liberal Treasurer Peter Costello announced the most recent inquiry into the financial system, headed by Stan Wallis. The Wallis Committee recommended removing the restriction on mergers between the banks and big life offices; stripping the Reserve Bank of its remaining powers to regulate the banks; and establishing a new banking regulator, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). What was previously the “six pillars” policy—the big four banks and big two life offices, AMP and National Mutual—was dropped in favour of the four pillars policy remaining today. The debate around the Wallis Committee also forced Peter Costello to confirm publicly, for the first time, that there was no formal guarantee of bank deposits in Australia.

Inside job

A member of the more recent Wallis Committee, Melbourne Business School Professor Ian Harper, made his own admission after the fact, in Lenore Taylor and David Uren’s 2009 book on the GFC, Shitstorm—Inside Labor’s darkest days. On the weekend of 11-12 October 2008—the very weekend the banks, including a very panicked Macquarie Bank, were begging the Rudd government for the guarantees they needed to stay afloat—Harper urged his wife to withdraw all she could from the ATM straight away, because he wasn’t certain the banks would open their doors come Monday. Meanwhile, the public were assured the banks were “sound”.

Footnotes

1. Edna Carew, Fast Money 4, p. 101-102 (Return to text)

2. Trevor Sykes, The bold riders, p. 3 (Return to text)

3. Katherine West, Discussion Paper 60: “Economic Opportunities for Britain and the Commonwealth”, Britain and the World, Chatham House 1995. (Return to text)

4. David Love, Unfinished Business: Paul Keating’s interrupted revolution, 2008. (Return to text)