Postal banking is undergoing a revival across the world. In particular, countries with a strong history of postal banking—such as the UK, France and Italy—have returned to the tradition in recent turbulent financial years.

A 2013 World Bank paper on “Financial Inclusion and the Role of the Post Office” pointed to the critical role of post office financial services in facilitating financial inclusion, particularly for the poor, less educated and unemployed, with accessibility increasing in proportion to the size of the postal network.

In Japan, home to the world-famous Japan Post Bank, 80 per cent of survey respondents held a post office bank account. Some countries recorded around 30 per cent with a postal account, but in most it was fewer than 10 per cent of respondents. Of 60 countries surveyed, seven had a licensed post bank; 29 had post offices offering deposit services without a banking license; and 24 nations operated banking services in partnership with other banks.

A push for postal banking is building in the USA. The US Postal Savings System was established in 1910 but discontinued in 1966. The service took deposits on behalf of banks and offered fixed-term bonds to savers. The rise of US Savings Bonds and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insurance of commercial banks is given as a cause of its demise, as it meant the service lost the advantage of its government guarantee of deposits and was seen as redundant. With today’s financial uncertainty that perceived redundancy has evaporated. Independent Senator Bernie Sanders campaigned for a revival of postal banking in his 2016 campaign and Democratic Senator Kirsten Gillibrand introduced the Postal Banking Act in 2018. After Sanders was defeated in the 2020 presidential primaries, the Joe Biden-Sanders “Unity Task Force” agreed to pursue a commitment to postal banking. In September 2020, Gillibrand and Sanders announced the latest version of the Postal Banking Act.

In a 17 September 2020 Facebook live conversation, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand pointed to the key factor: “The USPS is the only institution that serves every community in the country, from inner cities to rural America. The Postal Banking Act would reinforce the Postal Service, provide critical revenue, and establish postal banking for the nearly 10 million American households who lack access to basic financial services.” (Emphasis added.)

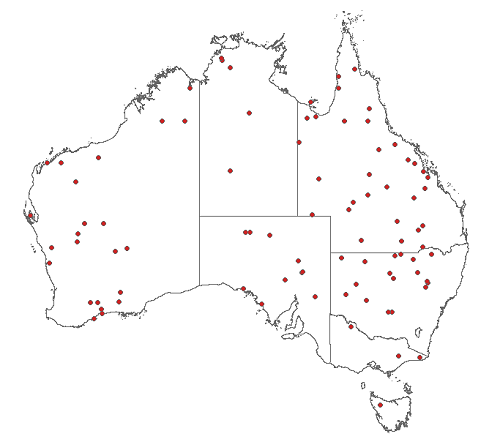

The same is increasingly true for Australia as banks continue to shut down branches and rip out ATMs. A June 2019 Reserve Bank of Australia paper on cash accessibility noted that “Australia Post’s Bank@Post service is the only in-person banking facility within a reasonable distance for many Australians living in regional or remote areas”. Australia Post is mandated by the Australian Postal Corporation Act 1989 to provide mail service that is “reasonably accessible to all people in Australia on an equitable basis”.

The accompanying map shows all Australian post offices further than 50 kilometres from the nearest bank branch. “Although government owned”, noted the RBA, “Australia Post is required to make a commercial rate of return and be self-funded, and so the ongoing financial viability of Bank@Post will be important to the continued existence of this service.”

In other words, let Australia Post go down the gurgler, and so will many people’s access to banking. Australia Post CEO Christine Holgate proved that securing Australia Post’s future depends upon securing its role in providing financial services. This took the form of: making the banks pony up the money for Australia Post branches to continue to take up the slack of declining bank branches; and prosecuting the case for a dedicated Australia Post Bank.

Other nations across the world have had the same experience. As digital technologies impacted mail services in the 1990s, and through the 2000s and 2010s, many postal services expanded into financial services to remain viable—particularly in those nations with a history of postal banking. Some of these outfits operate fully as banks, others function as proxies of or in partnership with private banks. Unfortunately, the deck is still stacked against these institutions, by bankers who recognise the threat to their monopoly power, but there is no denying the success and popularity of postal banking, which is why it keeps popping up in policy discussions.

New postal banks

France, which has a long history of postal banking, established La Banque Postale in 2006 operating through La Poste’s 7,700 post offices. With a mandate to provide banking services to the public, it has become a leading lender to local government authorities. In recent years there have been efforts to privatise the postal banking service; a 2020 merger means the French government is no longer the majority shareholder.

A bill establishing postal banking first passed in France on 9 April 1881. It was proposed by the undersecretary of state (later minister of posts and telegraphs), Adolphe Cochery, to be a nationwide postal savings bank. He stated: “The State has to achieve what cannot be done by private initiative. When private enterprise can attain its object, the State must disappear, but when private initiative is powerless, it is the duty of the State to lend its assistance. It is because the private savings banks cannot meet all the wants of the thrifty population that we submitted the bill which is under consideration.” Funds were to be invested in French government securities.

Italy in 1999 founded BancoPosta through postal service Poste Italiane SpA, which is 154 years old and 65 percent owned by the state with a network of 13,000 branches. BancoPosta does not have a banking licence but offers a wide range of financial and insurance services in partnership with private banks and provides access to services provided by government investment bank, Cassa Depositi e Prestiti. BancoPosta deposits are mostly invested in Italian sovereign debt. According to American Banker, in 2012 nearly 70 per cent of the post office’s profits came from financial services!

Italy first established a postal savings bank system in 1875. Purchasing government bonds became a popular investment at this time, facilitated by the postal system. Like in other nations, youth savings were promoted through the schools.

Ireland. An Post, literally “The Post”, in 2003 began to provide basic banking services in conjunction with Allied Irish Banks. In 2006 it initiated a financial products and services venture called Postbank, in cooperation with BNP Paribas, providing access to deposit accounts and government agencies through over 1,000 branches, but it was wound down in 2010.

Bulgaria Postbank, a subsidiary of the national postal service, was started in 1991. It was one of the few banks to survive the 1996-97 Bulgarian banking crisis. The major share was purchased by another bank in 1998 and after various other mergers and changes, the bank was removed from the postal network. Since 2011 banking services were no longer available through the post office.

Brazil. The national postal service established a postal bank in 2002 in partnership with the nation’s largest private bank, Bradesco. It now operates as Banco Postal as proxy for Banco do Brasil.

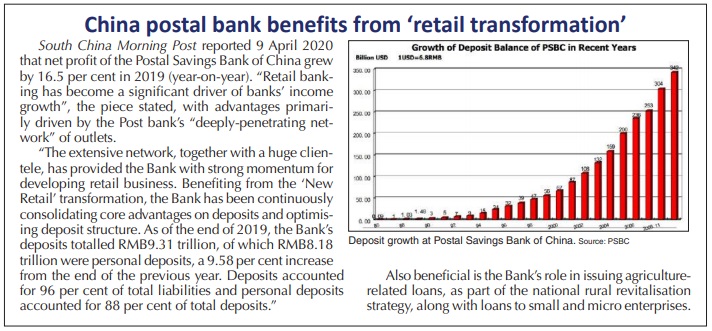

China. In the late 1980s a deposit-taking function was established at postal services, known as the Postal Savings and Remittance Bureau, with funds held at the central bank, the People’s Bank of China. Following the 2005 Plan on Reform of the Postal System, which prepared the way for a dedicated postal savings bank system, the Postal Savings Bank of China was founded in 2007. It provides banking services at post offices which comprise the second largest retail banking network in the country, covering 99 per cent of county areas in China. The Chinese government has utilised the service for poverty reduction loans. New Zealand is the other country that moved back to postal banking in this period.

NZ had started the Post Office Savings Bank in 1867, but it was split up and sold in 1987. In 2002, Kiwibank was established as part of New Zealand Post. (“Learn from New Zealand and Japan on postal banking”, AAS, 11 Nov. 2020.)

In addition to the current campaign to re-establish postal banking in America, there is a campaign in Canada which is fiercely opposed by the private banking monopoly.

Canada utilised postal banking from 1868 with services offered at the Post Office Savings Bank run by Canada Post. Deposits were transmitted to the Treasury. The Canadian Museum of History reports that “the savings of eastern and central Canada helped subsidise railroad construction in the West as well as from coast to coast.” The postal bank was shut down in 1968-69. The decision to abandon post banking, according to the museum, stemmed from a dimming “view of the role of government institutions in the banking sector”—in other words, the effective propaganda of private bankers.

In 2016 when the government announced a review of the postal service, postal unions launched a campaign to revive postal banking. According to the National Observer of 26 May 2020, in early 2020 Canada Post, in collaboration with the unions, commenced a study on reviving postal banking and set up pilot projects in a number of locations. In part justified by the spread of coronavirus, Canadian banks have been closing hundreds of branches and limiting operation hours. In British Columbia, over 60 per cent of rural communities have no access to banking.

Yet in response to the pilot, the Canadian Banking Association has dug its heels in against a postal bank, saying its position had not changed from its submission to the Canada Post Review Task Force established in 2016, which declared: “there is no public policy objective or existing gap in the marketplace that would necessitate the Government of Canada entering into the business of retail banking through Canada Post. Canadians are well served by Canada’s competitive, prudently regulated and effectively managed banking system.”

Ingrained in history

Unusually for postal banks, the Chinese, French and Japanese versions all hold universal banking licences and can therefore compete with commercial banks across the board.

Japan Post Bank has operated a continuous retail financial service since 1875 via 24,000 branches, with funds invested in infrastructure programs via government bonds. JPB is mandated to provide postal services across the country even if branches run at a loss. Japan’s post office generates 90 per cent of its income from financial services. In 2007 a ten-year privatisation plan commenced, to be completed by 2017, although the Japanese government must maintain control of more than one-third of Japan Post.

The UK established the first Postal Office Savings Bank, set up in 1861 by then Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone.1 Banks mainly operated in large cities at that time, leaving rural inhabitants to stash their money at home. Over 600,000 postal accounts were established within five years; by 1927, there were 12 million accounts. Banking initially consisted of savings deposits; investment in government bonds and other functions were soon added. In 1969 the institution was moved to the Treasury and transformed into the National Savings bank (later renamed National Savings and Investments).

National Girobank was a public sector bank established by the British Post Office in 1968 after a labour movement campaign asserting that banks were not providing adequate services to the public. The government of Harold Wilson passed an act enabling the new system, which shook up the British banking system, with one in every three pounds of cash deposits channelled into Girobank. It was the nation’s sixth largest bank by the late 1980s. In 1989 the government privatised the bank and it was taken over by commercial bank, Alliance Leicester. (Giro refers to a system based on direct transfers between accounts rather than cheques. Most European countries have run such as system at some point, mostly operating through postal services.) In 2009 a campaign to bring back Girobank commenced, led by unions and small business.

In 2015 the retail branch of the postal service, UK Post Office Ltd, launched Post Office Money to provide deposit accounts, credit cards, mortgages, personal loans and insurance. As it does not have a banking licence it operates in cooperation with the Bank of Ireland, transacting through post office branches.

In Germany, postal banking services existed since 1909, going through a number of incarnations. The German postal service was split and privatised between 1989 and 1995, with Deutsche Postbank continuing provision of banking services. Deutsche Bank bought 30 per cent of Deutsche Postbank in 2008, which now comprises Deutsche Bank’s retail arm, but banking services are still provided at postal branches.

Finland’s Post Savings Bank, founded in 1887, carried out full banking functions until 2000. It was merged with an insurance company and completely sold off in 2007.

The Greek Postal Savings Bank began in Crete in 1900, expanding to attract a large percentage of savings. In 2013 it merged with Eurobank Ergasias SA to become TT Hellenic Postbank.

The Netherlands founded the National Postal Savings Bank in 1881. It was fully privatised in 1986 and later merged with a commercial bank eventually forming ING Bank.

Switzerland’s PostFinance has operated financial services out of Swiss Post since 1906. It mainly conducted payments with a small share of savings and pensions, until 2013 when it was awarded a bank licence. On 20 January 2021, the Swiss government proposed full privatisation of PostFinance. Thanks to Switzerland’s powerful private banks, as a state-owned entity it cannot make loans or mortgages; it is also losing money due to the country’s negative interest rates. The Postal Act will have to be changed for privatisation to occur as currently Swiss Post must hold the majority of shares in PostFinance. The Act also obligates PostFinance to provide universal public services. According to swissinfo.ch, Switzerland’s Federation of Trade Unions opposes the plan, saying the institution is a people’s bank and belongs to the public.

In other European countries including Spain, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, post offices act as agents for private-sector banks. Sweden and Russia also have a history of postal banking.

In India the Government Savings Bank Act was passed in 1873 and the Post Office Savings Banks opened in 1882 providing basic banking services, taking deposits and providing remittance and life insurance along with distribution of pensions and other government services. India Post Payments Bank commenced as a dedicated banking service in 2018 through the world’s largest postal network of over 155,000 branches.

Singapore’s Post Office Savings Bank is its oldest continuous bank, established in 1877 as part of the Postal Services Department to provide banking services to low-income citizens. It was sold off in 1998.

Privatisation scourge

As mentioned above, full or partial privatisations threaten to, or have destroyed or constrained, postal banking systems in Japan, Ireland, the UK, France, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and Singapore. Likewise in Austria, the state-owned Austrian Post bank was sold after running into trouble in 2005. In 2020, however, the postal service launched a new bank, bank99, to service 99 per cent of Austrians, albeit with an emphasis on digital services as well as physical branches. It will provide savings and checking accounts and credit cards via 1,800 branches. Norway’s Postbanken, founded in 1948 and owned by Bank of Norway, was sold in 1999. Post, Telegraph and Telephone in Portugal, which operated postal and banking services was privatised in 2014.

This is not the complete story. There are a variety of other postal banks, including in Asia, South East Asia and Africa. What is clear is that postal banking is not a radical idea, but a common-sense solution to the problem of maintaining postal services and providing financial services which enjoys broad popular support—except from bankers who fear losing their private monopoly and the political forces they control.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 27 January 2021

Footnote

1. From the political fight for the postal bank, against the might of the City of London banks, Gladstone wrote the banks made it clear that: “The hinge of the whole situation was this: the government itself was not to be a substantive power in matters of Finance, but was to leave the Money Power supreme and unquestioned.”