Financial Services Minister Stephen Jones’s 31 July National Press Club announcement of new legislation to put banks under strong regulation to force them to crack down on the financial scams robbing countless Australians of their life savings is a cynical fraud. His words would sound promising, but for the fact that:

- Australia’s notorious “wet lettuce” regulators are not feared by the banks, working mostly through a collaborative “self-regulation” model; and

- Jones’s strategy was ghost-written by the Australian Banking Association (ABA), for the banks, throwing the majority of the blame onto the platforms where many scams originate, ignoring that the common denominator of all scams is banking and payments infrastructure.

A year ago Jones had agreed that Australia would likely follow the just-passed UK law which mandates that banks refund scam victims, telling ABC Radio in July 2023 that “we’ll probably look at something which travels in the same direction”. (AAS 31 July.) But around the same time, the ABA met with the UK’s Payment Systems Regulator, declaring afterwards that “a mandatory reimbursement model on banks alone does not create the most effective incentives for all organisations to work together to disrupt scams.” (Emphasis added.)

Jones clearly got the memo.

“Banks play Jones like their fiddle”, blared the headline of the “Margin Call” column in the 30 July Australian, reporting that Jones’s “masters occupy the deep-leather chairs of the Australian Banking Association, led by the indomitable former Queensland premier Anna Bligh. Not only is Jones wrapped tightly around her finger”, read the piece, “but this is also the worst-kept secret in Canberra. We have it on impeccable authority that the ABA all but writes the minister’s speaking notes.”

“Rear Window”, in the 1 August Australian Financial Review, joined in with “Stephen Jones shields banks in scam ‘war’”, citing numerous examples showing Jones’s language echoing word-for-word that of Bligh on the issue of scams. Jones cited UK bank lobbyists claiming the UK is attracting more scammers because of its new law, rather than the regulator which says scams have plummeted. At the Press Club, “After fielding questions, [Jones] returned to his table—seated opposite Bligh”, the article closed.

The ABA’s plan: shoot the messenger

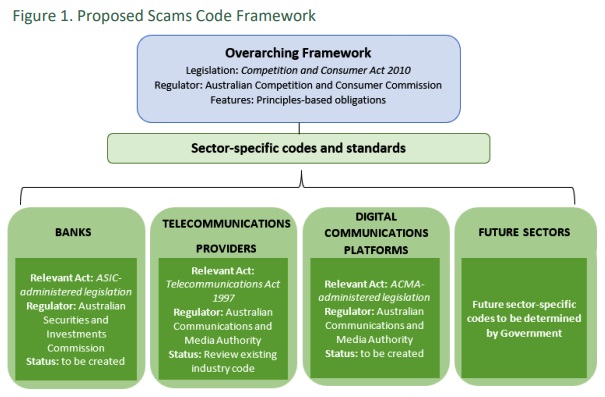

In April 2023 the ABA said that for six months it had been working on a new industry standard to counter financial scams. Floating the language Jones would later use at the Press Club, Anna Bligh insisted that banks are only one part of the “scams ecosystem”, telling ABC News on 20 April 2023: “Most scams arrive through the telecommunications system via an SMS or email, through an online platform or via an online shopping site, none of which are controlled by banks.” The Albanese government’s “Scams—Mandatory Industry Codes” Consultation paper was launched in November 2023, proposing regulation of selected businesses to assist in preventing scams. The ABA’s submission endorsed the Consultation’s “Whole of Ecosystem Application” for the new code, demanding digital platforms, online marketplaces (originally to be excluded), and telecommunications networks share the blame. It emphasised prevention and disruption of scams over customer refunds.

In his Press Club speech, Jones blamed social media giants as the main culprits “dragging their heels” in the fight against scams. He laid out the progress of the National Anti-Scam Centre’s taskforce blocking scam calls and texts, admitting it’s a case of “whack-a-mole”. He noted a 13 per cent fall in losses from scams comparing 2023 to 2022, but $2.74 billion was still stolen. His new legislation—actually weaker in the “prevention” department than the UK scheme—will require banks to strengthen controls over bank transfers; businesses to report scams and help customers; telecommunications companies to block scams; and social media to adopt stronger anti-scam actions and remove scam posts. Only if regulated parties “drop the ball and a victim loses money” will they have to compensate. Regulators—if they do their job—will levy penalties for non-compliance so there will be “a financial incentive to detect and disrupt scams”, Jones argued. A harsher financial incentive—victim compensation—will only be available “in the right circumstances”, he specified. It “should not be the first line of defence”. (Except compensation is a much more effective incentive than fines, and compensation goes to the actual victim, whereas fines go to the government.)

ABC’s National Regional Affairs Reporter Jane Norman, who moderated the event, grilled Jones on why a UK-style default compensation mechanism is not in his scheme, meaning victims have to “go through quite a few hurdles” for redress. Jones said he did not believe that the UK scheme—which commences in October—was a “fit-for-purpose” solution because while it delivered compensation it did not put enough emphasis on prevention. Norman persisted: “You can’t do both at once?” Claiming that is what he’s doing, Jones parroted the ABA line that if victims are always compensated “it makes you a resort of first option” that scammers will flock to. Noting the UK scheme is already followed voluntarily by many banks, Peter Martin from The Conversation stressed that the banks are the unavoidable pipeline for the financial transmission of any scam, regardless of where they originate or land. But Jones simply denied this reality, insisting that his scheme is superior because if banks breach the newly legislated standards, they will be “on the hook” for compensation. (But in a way that banks can fight in court, delaying and blocking most compensation.)

Alexandra Brooks from seniors’ community group Citro called out Jones for labelling social media platforms “offensive” when “it’s Australia’s banks that have behaved the most offensively over the last few years, letting criminals set up accounts that steal hardworking Australians’ money while blaming and then refusing to refund scam victims”.

Safeguards that aren’t

Jones’s claims depend on whether the new legislation has any teeth—unlikely—and on the reach of regulators, which have no form in actually policing. Furthermore, banks have slashed their capacity to assist customers in detecting and preventing scams. They don’t have branches and can’t be easily contacted. One of the most common stories from scam victims is one where the scam transaction is completed while they are on hold with the bank. The Treasury’s Consultation Paper states that “A bank must have user-friendly and accessible methods for consumers to immediately take action where they suspect their accounts are compromised or they have been scammed”, but only mentions an app-based measure. As the past year has shown, even when requested to pause branch closures by an Australian Senate inquiry, banks have refused to address this shortcoming.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 7 August 2024