The 28-29 June G20 Leaders’ Summit in Osaka, Japan ignored the reality that the world is staring down the barrel of a new financial crisis on par with 2008. The Communiqué released at the conclusion of the gathering of the twenty major economies and their central banks—which was established to come up with solutions following the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis—merely noted that “growth remains low and risks remain tilted to the downside”.

Chinese President Xi Jinping came closer to reality than most world leaders, warning in a speech that “Ten years after the 2008 international financial crisis, the global economy has again reached a crossroads.” The trade war with the USA has disrupted financial stability, he said, and “The world economy is confronting more risks and uncertainties, dampening the confidence of international investors.”

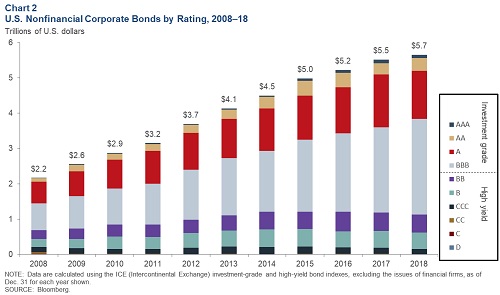

Over the last week numerous new warnings emerged. Joining the Bank of England, IMF, OECD, former US Federal Reserve officials and other experts warning of a collapse of the global corporate debt bubble this week, was the bank which directs central banks globally, the Bank for International Settlements. Its 2019 Annual Economic Report surveys the US$3 trillion market for leveraged loans, centred in the USA and the UK, which features deteriorating lending standards and a surge in products structured upon it (collateralised loan obligations, CLOs), “reminiscent of the steep rise in collateralised debt obligations that amplified the [2007 US] subprime [mortgage] crisis”. If this sector deteriorates, says the report, the impact “can run right through the banking system”. The problem is particularly visible “in the concentration of the outstanding stock of securities in the triple-B segment—just above non-investment grade (‘junk’ status)”. The report also warned of potential adverse outcomes from efforts to manoeuvre monetary policy given long-term low interest rates.

Economic nerves had been frayed in the lead-up to the G20 summit, for fear the US-China trade war would remain unresolved, or deteriorate, which could lead to a worldwide recession. The situation “is now teetering on the edge of derailing global growth”, wrote the London Telegraph on 24 June. UBS had warned that if new tariffs kicked in on 1 July it could spell global recession; it would be a “shove too far” for the world economy. The bank’s global head of economic research, Arend Kapteyn, said such tariffs would shift US and European growth expectations by around 1 per cent over a year and a half, provoking a “mild recession” akin to the mid-1980s oil collapse or 2009 Eurozone debt crisis, CNBC reported. An escalation of the conflict could also push global equities markets down by 20 per cent. CNBC cited a Wall Street brokerage firm telling clients the world was only “one step away” from recession.

Co-founder of the world’s largest hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, Ray Dalio, told the Australian on 28 June that the confluence of economic factors today “is most similar to the late 1930s”. This includes central banks’ limited capacity to stimulate the economy; political and social conflicts; and conflict with a “rising power”, namely China. “We are in a period of exceptional uncertainty. It is unusually risky”, he warned. Dalio shared a “scary thought”—that monetary policy would not get us out of a new crisis. “Australia is going to reach the limits of its debt-financed expansion” very soon, he said, as “there will be no more rates to cut”.

Another corporate debt warning came from head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) during the 2008 crisis, Sheila Bair. Speaking with MarketWatch on 24 June, she warned “distress in the corporate market” would have a major impact on the real economy. The effect would be more direct than that of the bursting subprime bubble, the impact of which was dragged out by the process of evictions and bank sales for a year or more. After a decade of easy money, she said, a credit crunch to highly leveraged companies would hit fast, causing defaults, shutdowns and job losses.

Collapsing banks

ABC News reported that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) intervened to inject liquidity into inter-bank lending markets at the end of May, when a Mongolian bank defaulted on an interbank payment. Regulators swiftly took over Baoshang Bank while $125 billion was injected into markets by the central bank to ensure adequate liquidity.

PBOC reported that the crisis at Baoshang, which has assets of $90 billion, a low rate of non-performing loans and capital buffers up to international standards, was triggered by misappropriation of funds by its largest shareholder. Regulators will direct the bank for one year, evaluating and restructuring its books while its normal functions continue; 99.98 per cent of creditors received full repayment of their funds, with only some high-yield investment products not paid out.

There are serious upheavals in Europe too, with axios. com reporting that “The GAM Greensill Supply Chain Finance fund, in Switzerland, imploded in early June, followed in short succession by Neil Woodford’s Equity Income fund in the UK. Then came French asset manager H20 Asset Management, running into similar problems.”

In the USA, all 18 mega-banks passed the second leg of the Fed’s stress tests, including the dangerous derivatives-riddled Deutsche Bank. The test is a joke, given that: the Fed uses the banks’ own model; banks including serial rule-breaker JPMorgan Chase were given a second chance after they failed the first time; the tests do not account for high-risk derivatives housed in offshore entities; and the Fed changed the rules of the stress tests in March so banks couldn’t be failed based on “qualitative” measures, like failing to abide by basic standards such as reporting money laundering, or scandals such as insider trading.

China, on the other hand, has high standards of bank regulation, including Glass-Steagall bank separation. Under its Commercial Banking Law, retail banks may not engage in speculative activity such as derivatives or stock trading, securities business (such as CLOs or CDOs) or real estate investment, and regulators inspect their books at random times. Consequently, China has a very low rate of derivatives compared with other countries, shielding its banks and depositors from speculative losses.

Australian Alert Service 3 July 2019