The floods which recently devastated Queensland and New South Wales are estimated to have caused $2 billion in damages. The NSW region of Lismore is one the most severely affected areas: more than 2,600 homes have been significantly damaged, and over 2,000 are considered uninhabitable. In Lismore, floods reached a peak of 14.37m, two metres higher than their previous 1954 benchmark. Sadly, four Lismore residents died in the floods.

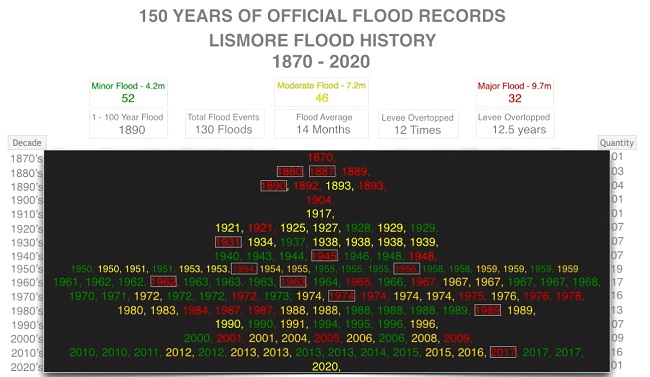

Lismore is one of the most flood-prone areas in Australia, experiencing more than 91 floods in 150 years. The four biggest floods alone (1954, 1974, 1989 and 2017) resulted in over $10 billion in recovery costs.

Desperate Lismore residents are the victims of an entrenched bureaucracy which has prevented effective flood mitigation and management. As reported 10 March 2022 by Sky News, “political bickering, gridlocked bureaucracy leaves [this] flood-ravaged town repeating history … one disaster after another can’t convince governments of any colour to stop their small city from drowning—over and over again”.

Sky News interviewed local resident Richard Trevan, who blasted the catastrophically delayed emergency response: “If the citizens of Lismore had not gone into their tinnies and risked their lives the death toll would have been unimaginable”.

Trevan stated that what “eats [him] alive” is the fact that he has spent the last five years “trying to highlight the problems in the system”. Trevan, a fifth-generation Lismore resident, is part of the Lismore Citizens Flood Review Group, which was formed after the devastating March 2017 floods, which, until now, had resulted in the highest damage bill in Lismore’s history.

The Review Group conducted a three-year investigation after the 2017 floods, conducting interviews and collecting evidence to produce a comprehensive report. Their aim was to “examine major aspects of the management of floods from the community point of view, and endeavour to recommend constructive structural and administrative changes that would ensure that the avoidable devastation that occurred … would never happen again.”

The Review Group distributed their report widely and gave presentations to a wide range of audiences, including: the local community; state and federal politicians and bureaucrats; senior management at the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) and the Office of Emergency Management; local government; and Southern Cross University, at an event which was attended by over 100 government agencies and non-profit organisations. Unfortunately, the Review Group states that their recommendations have thus far been ignored by NSW State Emergency Service (SES), BoM and many other relevant organisations.

The outcome of the Review Group’s three-year investigation exposed key elements of the dysfunctional flood management which severely impacted the community, including:

- SES Incident Management staff did not follow official incident management procedures, instead cherry-picking aspects to follow and ignoring the rest. The report documented a deficiency in the requirements of credentials for salaried SES management staff—only eight people within NSW emergency services had the required credentials to participate in international operations. An Assistant Commissioner at SES had risen through the ranks from an administrative position and had no formal qualifications or field experience.

- The communication of flood warnings was a disaster. Emergency agencies communicated information primarily through social media and various websites; however, about 20 per cent of Lismore’s floodplain community did not have a computer or smartphone. The SES SMS warning to evacuate was the first time most of the community became aware that there would be a major flood. The SES communicated “detailed, badly prepared, vague expressions and imprecise timings”, and left out vital information. The BoM’s poorly worded warnings underestimated the developing crisis, were far behind the evolving situation, and included incorrect geographical information. The report documented the skill and knowledge of the local Lismore City Unit SES Flood Intelligence Officer, who could accurately predict flood peak height and timing with a pen and paper; in contrast to the BoM, which, despite its government funding and “superior” technology, was not capable of the same accurate or timely predictions.

- SES only viewed preparedness as an internal action. The agency had no defined responsibility to give the community early warning. During the March 2017 flood, the very experienced local SES team was only informed of the impending flood by fax, 24 hours after the NSW SES activated its first incident plan. From experience, the local volunteer Lismore SES knew that after six hours of very heavy flood rain there would be a major flood, and therefore began to make preparations. The Lismore SES knew that the community would have at least 14 hours to pack up and prepare, however they had no authority to make public announcements. The first effective notification that alerted the whole community to the flood was the evacuation order, which was issued 29 hours after the SES activated its first incident plan.

- The Review Group asserted that local knowledge and experience was the most valuable resource in an emergency; however, SES management arrogantly ignored it, with tremendous cost to the community. Lifelong residents of Lismore with valuable knowledge of flooding tried to warn SES management about the magnitude of the impending floods, but were ignored. Lismore City Unit SES volunteers are “well trained and are very experienced in managing floods and other emergencies in their local area over many years, some even decades”. However, the local SES was “sidelined by bureaucrats … their knowledge and advice was ignored resulting in $10s of millions of avoidable damage”. At the time of the March 2017 flood, there was no one in SES senior management or the Incident Management Team with any knowledge or field experience in flooding of the Richmond Catchment area.

- The report revealed a clear variation in focus between the community and the SES. The community focus was personal: saving lives, businesses, livelihoods, and reducing stock and property losses; therefore, early warning was the primary focus. The SES and emergency management agencies’ focus was operational: preparation, rescue and recovery; therefore, resource management was the primary focus. An example was given: early on in the flood situation, helicopters were seen parked nearby, indicating that SES must have ordered them expecting a major flood; however, no indication of the incoming flood was given to the community. (SES later defended their actions, stating “We wanted to be prepared”.)

- There was no accountability for the disastrous flood management from NSW SES, which “whitewashed” its culpability, and made no effort to engage with the community. SES facilitated only one postevent public meeting with the community, wherein citizens were told they were not permitted to ask questions, and Lismore’s local SES volunteers were not permitted to speak. SES management staff who failed to listen to local knowledge, which had caused tens of millions of dollars in avoidable damage, were promoted shortly thereafter. A review of the 2017 floods commissioned by SES, which recommended more centralisation and more bureaucracy, did not consult with the community.

The Review Group concluded: “The $3 billion losses experienced regularly in our local area with each major flood is unsustainable and too important to the nation. Functional and professional management systems and personnel across all levels are required in every emergency agency. Arrogance, ignorance, ego, inter- and intra-agency territory and power struggles, confusion and uncertainty have no place in emergency management. A bureaucracy containing career-oriented personnel micro-managing and making decisions from 600 kms away with no local knowledge will never replace the locally managed, competent teams who previously operated with few resources and did a superb job. This is a critical issue that must be addressed and resolved as a matter of urgency.”

Prior to 2010, flooding in Lismore was effectively managed by the local community. Farmers and citizens would phone in real-time information to local radio stations; or the local SES Lismore City Unit and SES Regional headquarters, which communicated with BoM staff in Brisbane and Sydney. Hourly flood updates and real-time information was relayed by local radio stations, and residents and businesses made their own decisions about what they needed to do and when. The Review Group states that this “was a low cost simple system with high quality outcomes. We now have a high cost system with low quality outcomes”.

In 2010, a fear of litigation resulted in an amendment to the State Emergency and Rescue Management Act 1989, which now stipulated that all flood management must be controlled by SES management. No local emergency information could be broadcast unless it came from SES management or BoM. The result was a multi-hour lag in flood information communication, which costs the community valuable preparation and response time.

Despite Lismore’s long history of floods, over the past 70 years there has been no coordinated local, state and federal government investigation of flood mitigation solutions for the area, and Lismore never seems to get on “the list” of significant state infrastructure projects. Although Lismore has a levee, which was built in 2005, it was only designed for a 10 per cent Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP) (“1 in 10- year flood”) event. During the 2017 floods, the levee was overtopped for the first time when flooding reached up to 5 per cent AEP (“1 in 20-year flood”), and in some areas, 1 per cent AEP (“1 in 100-year flood”) levels. A November 2020 study undertaken by the Lismore Shire examined options to mitigate future floods, and found that spending just over $14 million on mitigation could save an estimated $277.3 million in flood damages in the event of a 5 per cent AEP event, and an estimated $44.7 million in the event of 1 per cent AEP event.

In addition, although Lismore is the most flood-affected postcode in Australia, the area also has a water security problem—the region can’t guarantee water for 110,000 residents past 2024. Members of the Review Group have stated that the region’s entire water catchment needs to be evaluated, the magnitude of the problem means this must be coordinated by the federal government, with input from state and local governments. Richard Trevan told Sky News that NSW bureaucracy was “seriously out of touch” with water security and flood mitigation requirements.

The Review Group made a submission to the 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, which included an impressive audio-visual presentation which illustrated their research. However, in public hearings lawyers representing the NSW government tried to convince the Commissioners to discount the Review Group’s research. As reported by Sky News, the NSW Government is now accused of ignoring the recommendations of the 2020 Royal Commission, which found that emergency information and warning systems across Australia needed urgent reform.

Unfortunately, the recent floods which have devastated Lismore have confirmed that, despite the Review Group’s entreaties, the dysfunctional flood management has not changed. This was starkly illustrated when Lismore residents had to crowdfund their own helicopters to organise supply drops to stranded residents. NSW SES had twice rejected offers of help from the Australian Defence Force; and sent private helicopter pilots home saying that they were not needed, despite the fact that the pilots were being paid by the government to be on standby.

By Melissa Harrison, Australian Alert Service, 23 March 2022