25 Aug.—As it has been doing for some months now, the Morrison government continues to exploit the COVID-19 pandemic both to justify and to expedite the Canberra “national security” establishment’s grab for ever more police-state powers. Though the usual bipartisan consensus on such matters has not yet failed, it is however at least faltering, as the Labor Party digs its heels in over the government’s push to legislate sweeping new powers for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) and Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) before it releases the already much delayed report of the “Comprehensive review of the legal framework governing the National Intelligence Community”. Led by former ASIO director-general and retired Defence Department head Dennis Richardson, this review was completed late last year but is still being withheld from Parliament. Meanwhile the fact that the very government departments that have hyped the threat of “foreign interference” and “cyber-enabled espionage” have for years not been bothered to enforce mandatory security standards across the federal bureaucracy, or even follow them themselves, raises serious questions as to whether those threats even exist, let alone justify the kind of arbitrary arrest and mass surveillance powers the government and intelligence agencies demand.

As the Australian Alert Service has reported, the Morrison government wasted no time in seizing upon the pandemic-induced restriction of normal Parliamentary functions to try to accelerate Australia’s slide towards a fullblown police state. In March, shortly after a public health emergency was declared and travel restrictions put in place, Minister for Home Affairs Peter Dutton introduced the Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (International Production Orders) Bill 2020. Ostensibly the IPO Bill is designed to “establish a new framework to assist Australia’s international crime cooperation efforts”, to which end Canberra is seeking “agreements with like-minded foreign governments for reciprocal cross-border access to communications data”. The bill would sidestep the prohibition on the ASD spying on Australians by allowing domestic spy agency ASIO, authorised by a verbal directive from the Attorney-General, to access real-time surveillance information collected by the intelligence agencies of the aforementioned “like-minded” countries, i.e. the rest of the Five Eyes spying alliance (the USA, the UK, Canada and New Zealand)—thus retrospectively legitimising those agencies’ illegal and still ongoing mass surveillance their own and each other’s populations, which American intelligence whistleblower Edward Snowden exposed in 2013.

Then in mid-May Dutton introduced the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Amendment Bill 2020. If passed, it would let ASIO detain and interrogate children as young as 14 whom it deems “likely” to engage in espionage, “politically motivated violence” and/or “foreign interference”, instead of only terrorism suspects aged 16 and over as at present. It would also allow either a governmentselected judge or a member of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (the ostensibly independent body that reviews decisions made under federal laws), without evidence, to stop a person ASIO is seeking to question from contacting his or her lawyer, and assign a “suitable” one instead, purely on ASIO’s say-so. And where a suspect’s own lawyer is initially approved, ASIO can revoke that approval at will if, per the bill’s Explanatory Memorandum, it decides that “the lawyer’s conduct is unduly disrupting questioning”. According to Law Council of Australia President Pauline Wright, the coercive questioning powers the bill would confer are without precedent either in Australia or any Five Eyes country. The bill also proposes to empower ASIO officers to plant electronic surveillance and tracking devices on whomever they want, without a warrant.

Furthermore the new Minister’s Guidelines for ASIO, which Dutton tabled in Parliament out of session earlier this month, are deliberately vague as to both whom ASIO can or should target for surveillance, and how it should store and dispose of the information it gathers. Ms Wright, in a 20 August statement, noted that whilst the new guidelines “contain several valuable improvements from the previous iteration” set forth by the Howard government in 2007, they also have major problems in two key areas. The first, she said, is that “essential matters, such as guidance on the collection, use, disclosure, storage, destruction or retention of particularly sensitive information, is not covered in the Guidelines. An example would include information subject to client legal privilege or relating to journalists and/or their sources or health information.” The second key concern, she continued, is that “there is inadequate guidance on proportionality and how an ASIO officer would assess and compare the level of intrusiveness when it comes to surveillance”—a particularly important area “given recent major expansions to ASIO’s powers, including encryption legislation passed in 2018”, Wright said, and made more so by the proposed amendments. “These Guidelines fail to give the public a clear understanding of how any degree of intrusion will be assessed by ASIO.”

Will Labor break ranks?

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) opposition objected to the IPO Bill in its present form, after Shadow Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus MP identified a loophole that would allow ASIO to use an International Production Order to bypass (already woefully inadequate) protections for journalists. It did not, however, voice any complaint about the ASIO Amendment Bill, and—having endorsed the recommendations of a 2018 review by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) around which it was designed—seemed inclined to support it. Whilst this will likely remain the case, it cannot yet be taken for granted, after Dreyfus on 19 August issued what could be read as a veiled threat to stall the whole package of so-called national security legislation over the government’s blatant attempt to avoid even the pretence of proper debate. At issue, as noted above, is the government’s effective demand that Labor support the expansion of ASIO’s powers—and be seen by the public to have done so—before it is even allowed to see the Richardson Review’s conclusions as to the efficacy of the current legal framework. Billed as the biggest review of Australian intelligence and national security laws in 40 years, the Richardson Review was commissioned in 2018 on the recommendation of the Independent Intelligence Review conducted by retired senior public servants Michael L’Estrange and Stephen Merchant the previous year. It is also the first exercise of its kind since the 11 September 2001 (“9/11”) terrorist attacks, in which time Australia has passed a world-record 85 national security laws. “Mr Richardson handed in his report to the government prior to Christmas last year”, the Sydney Morning Herald reported 19 August, “and the government has been sitting on an unclassified version of the document since early June.” Attorney-General Christian Porter MP has reportedly not set a date for its release; he has said only that the report will be made public “in the coming months”, blaming COVID complications for the delay.

According to SMH, Dreyfus was highly critical of the government’s failure to publish the unclassified version. “Labor agrees that aspects of this review into our intelligence services have to remain confidential”, he said. “But we also believe the Australian people have a right to know what their government is doing to keep them safe.” What really seems to have got Dreyfus’s goat, though, is that the government is refusing to show Parliament the classified version either. “Parliament is currently debating a range of legislative proposals that are directly or indirectly relevant to Mr Richardson’s review”, he said. “To withhold Mr Richardson’s report from the Parliament, while at the same time asking the Parliament to debate and pass changes to the legislative framework governing the National Intelligence Community, is contemptuous of the Parliament, disrespectful to the Australian people and is likely to result in poorer, less informed debate. That means poorer policy outcomes.” Left unsaid is that presuming the review were honest, it might well call into question whether some of ASIO’s current suite of powers are even necessary (given, as has been publicly acknowledged, that many have never been used), let alone the proposed raft of new ones.

As AAS has previously noted, making it more likely that Labor will support the ASIO bill regardless is that ASIO’s current questioning powers “sunset” (expire) on 7 September, by which time amendments must have been passed for it to keep operating. Labor’s usual modus operandi when in opposition is to make token complaints about bad laws, then wave them through anyway on the premise of their supposed urgency, and promise (but fail) to fix them when next it is in government. That said, Dreyfus’s sudden outspokenness against the government’s end-run around Parliamentary process, coupled with his earlier skewering of the IPO Bill, are the strongest sign of defiance Labor has shown in some while.

Do as I say, not as I do

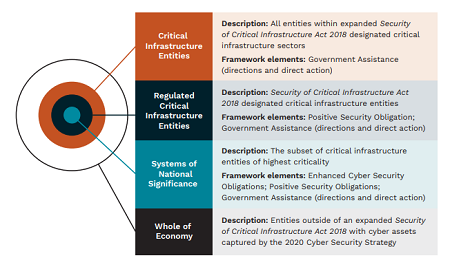

Parallel to its push to expand the intelligence agencies’ powers, the Morrison government is also pushing to expand the areas of society and the economy to which those powers apply, under the guise of protecting the nation’s “critical infrastructure” from attack—especially, it would seem, from cyber attack. In a discussion paper published 6 August, titled Protecting Critical Infrastructure and Systems of National Significance, the Department of Home Affairs proposes to expand the definition of “critical infrastructure” under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 from such things as electricity, gas, water, mass transport, communications and payments systems. Under amendments foreshadowed in the discussion paper, but which Dutton has yet to introduce in Parliament, it would now encompass the whole banking and finance sector, universities, the food and grocery industries, and more. And as a celebratory “exclusive” published that day in the SMH reported, the owners and operators of all of the above “will be forced to pass on information … to the Australian Signals Directorate in real time, and potentially allow the cyber spy agency into their networks to fend off major hacks. … At the lowest level, this would impose an obligation on companies to send the ASD ‘signatures’—a file containing a data sequence used to identify an attack on the network—when they are being attacked. Under the approval of Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton, the ASD could also be given access to the network to monitor and defend against significant cyber attacks.” In other words, the ASD would be able to intrude into virtually every aspect of Australians’ lives, right down to your grocery shopping, all on Dutton’s or his successors’ say-so. All it would take is a cyber attack that could just as well have been launched by the ASD itself, or by some provocateur in the Five Eyes’ employ.

Yet Home Affairs’ constant hyping up of the supposedly dire threat of cyber attacks is given the lie by its own behaviour, and that of the rest of the Commonwealth bureaucracy. “The great majority of government departments”, reported Crikey.com.au political editor Bernard Keane on 18 August, “don’t comply with the [government’s own] most basic cybersecurity standards”. In 2013, Keane explained, the government mandated that all agencies be compliant with the ASD’s “top four” mitigation strategies—application whitelisting, patching applications, restricting administrative privileges and patching operating systems—by July 2014. “In ASD’s view, if the ‘top four’ strategies … were put in place, 85 per cent of cyber intrusions would be prevented. … [But] more than six years after the deadline, few agencies are compliant with the top four.” And Home Affairs is among the worst offenders, Keane reported, having been found non-compliant by the Australian National Audit Office for seven years straight. “It’s almost enough to make you wonder whether it’s all a cover for handing ever more power and money to unaccountable national security bureaucrats.”

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 26 August 2020