The New Payments Platform (NPP) was the brainchild of the “self-regulating” Australian Payments Council, in response to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s call for industry to address potential innovation gaps in the payments system. From its 2013 inception, the coordinator of the NPP has been global accounting and auditing firm KPMG.

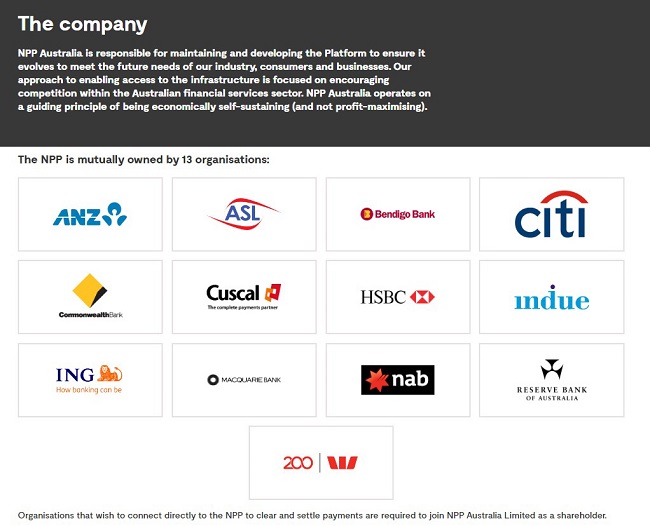

The NPP is a clearing system for fast payments, a financial utility owned and operated by a private company, NPP Australia Limited (NPPA). NPPA is owned by its thirteen founding shareholders: mostly banks, including Indue (the company that administers the government’s “cashless welfare card”) and the Reserve Bank.

RBA Governor Dr Philip Lowe wants the NPP to be the backbone of Australia’s payments system. The RBA has moved on from stern words, to now approving financial sanctions on banks that don’t get on board. The RBA has significant regulatory powers—it can decide to designate a payments system as subject to its regulation and impose mandated functions and an access regime. Philip Lowe has made it clear this option is on the table if Australia’s major banks don’t move over to the NPP. It’s not cheap for banks either—Westpac’s CEO lamented that the bank had spent hundreds of millions of dollars “for no return”, to upgrade their systems to be compatible. Joining the NPP itself is expensive: would-be NPP participants are required to purchase at least $2 million worth of NPPA shares at $1,000 per share. If an NPP participant wants to leave, they can redeem their shares—for $0.01 per share.

Australia’s domestic banks have traditionally used a variety of electronic messaging systems for their payments. The evident “advantage” of the New Payments Platform: its requirement that the Reserve Bank act as settlement intermediary for every domestic, government and cross-border transaction. Every transaction on the NPP must pass through a network operated by the SWIFT interbank payments network—which got a $1 billion, 12-year contract to build and operate the system.

The NPP is a bank-to-bank electronic messaging network; it doesn’t actually transfer funds. The RBA provides settlement for every NPP transaction, debiting/crediting accounts the big banks hold with the RBA. To fulfil the NPP’s promise of “near real-time” 24/7 payments out of business hours without incurring “credit risk” to the banks, the RBA provides liquidity with “open-dated repos”. What could go wrong?

Many of the NPP’s supposedly “innovative” capabilities are offered by other providers and technologies, like PayPal, cryptocurrencies or IBM’s “World Wire” network. These are more efficient and cost-effective solutions that don’t require banks to change their existing systems. They also don’t require a central bank intermediary, which apparently doesn’t sit well with the RBA.

Why is the RBA so adamant that Australia’s major banks must change their infrastructure to accommodate the NPP, even approving hefty fines for banks that don’t comply? Answer: there is a lot of money, power and control to be had here.

The ACCC acknowledged possible cartel, exclusionary and anti-competitive provisions in the NPP’s regulations, but allows them as the NPP is “in the public interest”.

The breadth of the NPP’s data collection goes far beyond financial information, to include our “opinions” and “personal information from oral sources”. The NPP’s “PayID” digital identity service may soon be joined to “TrustID”, to be used for all government services (another brainchild of the Australian Payments Council). It is unclear how NPPA intends to leverage this behavioural and transactional data, which is to be stored by NPPA or an undisclosed third-party provider. The international Financial Stability Board says that using third-party providers for important financial information has serious risks, not only technical (what happens if the company’s systems are down or they go insolvent?) but also legal—how can regulators audit a bank’s records if the third party’s contract gives it exclusive right to that data? The Financial Stability Board warns that this “could ultimately undermine financial stability”. Philip Lowe is a member of the Financial Stability Board—why isn’t he protecting Australians?

The Black Economy Taskforce Report, which recommended the government’s $10,000 cash ban, says the NPP is a “gamechanger” which will “replicate some of the features of cash”. Taskforce head Michael Andrew said in a 2017 interview with CPA Australia that the underlying macro-strategy was “to shift from a cash-based The NPP’s website identifies all of its shareholders, including the major banks and the Reserve Bank, which means the RBA is in a business partnership with the banks it oversees as the chair of Australia’s Council of Financial Regulators. www.cecaust.com.au Vol. 22 No. 3 22 January 2020 Australian Alert Service 5 economy into a non-cash economy … where we can therefore monitor and measure people’s activities”. The Black Economy Final Report says at the “vanguard of the information revolution” are firms that recognise the potential for data “to identify commercial opportunities (whether in finance or understanding consumer behaviour)”, and that “moving people into the banking system … [will] significantly improve both the quality and range of data at the disposal of agencies.” (And the banks.)

The NPP puts the RBA in the middle of every transaction. Total centralisation offers unprecedented opportunity for surveillance, data mining and financial control. The Bank for International Settlements (the “central bank of central banks”) says that “wider digital access” to the central bank can strengthen the pass-through of monetary policy, such as deep negative interest rates.

At the December public hearing of the cash ban’s Senate Inquiry, the RBA’s Dr Tony Richards said the idea that the cash ban could be a precursor to “the imposition of negative interest rates” or “the government deciding to withdraw cash from circulation” was “far-fetched”. Other central bankers don’t seem to think so. Erkki Liikanen, former Governor of Finland’s central bank, says the “zero lower bound problem” results from the availability of cash as an alternative, which “makes it difficult, perhaps impossible, to push market rates very far into the negative territory”.

RBA Governor Lowe says he expects the NPP to be a significant driver in reducing the use of cash in the economy. Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank (2012-19), tells central banks looking to issue their own “Central Bank Digital Currency” that to pass on negative interest rates, cash doesn’t need to be abolished entirely, “rather that it no longer acts as an effective competitor for large transactions.” Cash bans effectively eliminate cash as a legal competitor for large transactions.

The NPP. The RBA. KPMG. The Black Economy Taskforce. All drivers of a financial system with less cash, less privacy and more control over the people. They all intersect: Taskforce head Michael Andrew was formerly the global head of KPMG, which wants the cash ban lowered to $2,000. The RBA’s monetary policy benefits from the ban eliminating cash as “a competitor for large transactions”. It’s worth noting that NPP coordinator KPMG also provides advisory and auditing services to the Reserve Bank. (Ironically, KPMG also runs the RBA’s corruption hotline.)

Underneath all the financial plumbing, the NPP operates on the SWIFT interbank payments network. This may expose Australia’s economy to systemic geopolitical risk. SWIFT claims political neutrality, but has demonstrated it is willing to be weaponised by the US government, allowing financial sanctions to be imposed on countries such as Iran and Russia through the SWIFT system. In December 2019 the US government threatened Germany with economic sanctions to prevent development of a new RussianGerman gas pipeline. A spokesman for Russian President Vladimir Putin said these actions were in violation of international law, “a perfect example of unfair competition, an attempt to artificially secure [US] dominance in the European markets”. Germany has called for SWIFT to end the US dominance of the international payments system, with Europe now looking to develop its own payments system parallel to SWIFT.

China is Australia’s largest trading partner, receiving one third of our exports. Recently US-China tensions have escalated. Will the USA threaten to impose economic sanctions on Australia if we continue trade with China, through a systemically integrated NPP/SWIFT system? This could threaten not only Australia’s international trade, but the ability of our domestic and government payments systems to function at all.

Has the RBA potentially exposed Australia’s entire financial system to becoming hostage to US dominance, through the Trojan horse of the New Payments Platform? The RBA’s decision is in direct contrast to Europe and countries such as Russia, China and Iran, which have acknowledged the danger of dependency on SWIFT and are actively working to develop independent payment networks, protecting their economic sovereignty from US dominance and foreign interference.

In the interest of the Australian public, greater oversight and regulatory control of the New Payments Platform and the actions of the Reserve Bank is required. It is difficult to see how the New Payments Platform could be conceived as universally “in the public interest”.

Social anthropologist Bill Maurer says in his 2012 paper “Late to the party: Debt and data” that “money is not just debt and credit. It is also a public infrastructure for value transfer. We are entering a world where the public interest in payment must be defended.” The Australian people deserve better, in this arena “where consumer finance protection meets digital ‘bills of rights’”.

By Melissa Harrison. Published Australian Alert Service, 22 January 2020