Taking aim at the AUKUS trilateral security partnership, in early August former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating breathed words that should shame the current PM: “In defence and foreign policy, this is not a Labor government”, Mr Keating said. “… This is a sellout.”

Labor is a sellout on economic policy too. This week Treasurer Jim Chalmers blasted the Reserve Bank of Australia for “smashing the economy” with its rate rises, after campaigning for ten months—since he introduced the Treasury Laws Amendment (Reserve Bank Reforms) Bill in November 2023—to remove the Treasurer’s power to override the Reserve Bank on things like overzealous rate rises!

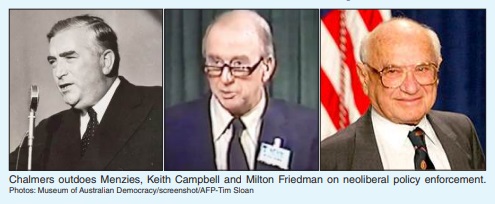

That override power was legislated by the Labor government of John Curtin and Ben Chifley in 1945 as a recourse to democratic procedures in the extraordinary event that the government and bank came to an impasse on monetary policy matters, as had occurred when Commonwealth Bank Governor Sir Robert Gibson refused to provide credit to the government during the Great Depression. Despite attacking the power—contained in Section 9 of the 1945 legislation—incessantly from the 1945 debates ahead of its passage through until the legislation was revisited in 1951, and again in 1959, the Liberal government of Robert Menzies did not repeal the power. (“Chalmers’ RBA reforms: The next chapter in the private hijacking of Australian banking”, available at citizensparty.org.au)

The power was rewritten slightly, and given other changes became Section 11, but the bottom line remained the same: the bank would be required to give effect to the Treasurer’s stated policy. All the bluff and bluster of 14 years evaporated and the Liberal government left the power unchanged. As were powers contained in companion legislation, the Banking Act 1945, which allowed the RBA to control the advances and interest rate policies of private banks. Together these provisions had been denounced by Liberals as “tyrannical” and “dictatorial”, equivalent to the controls of Nazi Germany. (AAS Almanacs, 21 and 28 Aug.)

The Liberals, in a postwar period that would see the rise of neoliberalism globally, did not see fit to remove the Section 11 power—but Labor’s Jim Chalmers does.

Neither did the final report of the Campbell Inquiry which became the script for neoliberalism in 1980s-90s Australia, released in September 1981. The inquiry, which was advised by none other than Austrian School economist Milton Friedman and the world’s biggest banks, made detailed recommendations regarding the independence of the Reserve Bank. Commenting on the Section 11 powers it ruled that “in the determination of overall monetary and banking policy the Bank, while having the power to formulate policy, is ultimately subordinate to government.”

Notably, the Campbell Inquiry’s reading of the power states that a difference of opinion between the Government and Bank board over monetary policy ultimately relates to “whether that policy is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia”—per the Bank’s mandate. (This indicates Chalmers’ attempt to put a “public interest” padlock on s.11 is superfluous.) Further, it states that “there has never been an irreconcilable difference of opinion of sufficient magnitude as to require reference to the Parliament”—and indeed there hasn’t been since.

The report notes that the inquiry received submissions calling for “absolute statutory independence from government” of the Reserve Bank in the determination of monetary policy, but found that such proposals would “amount to the substitution of bureaucratic for political discretion which would be inconsistent with the processes of democratic government.”

“In short, the Committee is firmly of the view that ultimate determination of and responsibility for overall economic policy—including monetary policy—cannot be effectively divorced from government and Parliament. It is also important that the monetary authorities be effectively accountable to the public and the Parliament.”

The committee ruled that “the Reserve Bank has all the formal powers it needs to effectively formulate and implement monetary policy”.

Section 11 empowers the RBA, not just the Treasurer, to bring matters to the Parliament’s attention, the report stated. “Ultimately, however, the Bank cannot rise above the source of its powers—government and Parliament—and must be responsive to the direction which governments may deem fit to give.”

“Accordingly the Committee recommends that:

(a) Existing provisions of the Reserve Bank Act defining the overall policy relationships between the Bank, the Government and the Parliament be retained.

(b) In particular, the Committee sees no need for change in the present provisions for resolution of differences of opinion between the Reserve Bank Board and the Treasurer (Section 11).”

The committee found that in all areas relating to the bank’s policy functions, “the Reserve Bank is accountable to the Government for its administration of policy. The Committee sees these matters as providing adequate safeguards in a democratic society.” (Emphasis added.)

Why is Treasurer Chalmers—who wrote an entire essay in late 2022 cheerleading “democratic reform” and “values-based capitalism” and criticising the neoliberal model—intent upon outdoing even the neoliberals’ blueprint for reform?

Why does he want to remove the power when it has never been used, and there was no public clamour for it? Indeed no one can even say where the recommendation originated, bar a single overseas submission. There is only one reason—to send a signal to the Bank for International Settlements and International Monetary Fund that Australia is on board with their demand for complete separation of banking from the oversight of elected bodies.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 4 September 2024