Australia’s high fuel prices and insanely small fuel reserve are the legacy of decades of government policy to allow “the market” to dictate Australia’s resources policies. It wasn’t always so. There was a political battle in the 1970s to establish national control of Australia’s resources, including national development and processing of petroleum. If it had succeeded, today the nation’s fuel prices would be cheaper and fuel supplies would be far less vulnerable to global events. It didn’t succeed, however, and Australians have been paying for it ever since.

The government of Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was fiercely determined to end foreign control over Australia’s natural resources. After his election in 1972, Whitlam created the Department of Minerals and Energy, appointing visionary nationalist Rex Connor to lead it. Connor was deeply committed to developing Australia’s resources sector under a government-directed national mineral and energy policy, declaring in Parliament on 12 April 1973 that “[j]ust as it has been stated that war is much too serious a matter for generals to control, so a Labor Government says that exclusive control of Australia’s fuel and energy resources is much too serious to be left to individual companies”.

The Whitlam government pursued its policy objectives through a number of ambitious resources projects. This included efforts to greatly expand the remit of the Australian Industry Development Corporation (AIDC), a national resource development fund which was previously championed by Liberal Prime Minister John Gorton and Country Party leader John “Black Jack” McEwen.

Under Connor’s leadership, a national Pipeline Authority was established in 1973, which was intended to facilitate the construction and operation of a vast transcontinental pipeline grid. The Authority could buy and sell petroleum; regulate natural gas prices; secure petroleum reserves; and was intended to ensure uniform gas prices across the country.

In addition, the Whitlam government established a Royal Commission into the petroleum industry; introduced stringent export controls on the minerals industry to ensure fair prices; encouraged Australian firms to deal collectively with foreign cartels to strengthen their negotiating power; and directly intervened in contract negotiations to insist upon higher prices.

Prior to 1972, the federal government did not collect data or statistics on mining investments or contracts, and very few official figures were maintained on the extent of foreign ownership of the industry, or of how much profit went overseas. Connor commissioned the Fitzgerald Inquiry to report on the “contribution of the Mineral Industry to Australian welfare”. The inquiry’s explosive findings revealed that in the preceding six years, mining companies had received more in tax concessions and subsidies than they had paid in taxes and royalties, and around half of company profits were sent overseas. The Whitlam government ended the tax concessions for the mining industry which had allowed multinationals to pay minimal or negligible taxes, while enjoying immense profits.

In a 19 March 1973 speech to the annual dinner of the Australian Mining Industry Council (AMIC), the industry’s peak lobbying body, Whitlam threw down the gauntlet: “We shall do business, and we shall do it with honour; but we do not regard the rape of our resources as inevitable, and we certainly do not intend to lie back and enjoy it. … We need to be satisfied that our mineral export policies and practices are in the best interests of Australia and our trading partners. It is perfectly clear that large companies with interests crossing many national boundaries may conduct their business in a way which, while maximising returns for themselves, will be to the detriment of a particular country. We will satisfy ourselves that those companies operate in Australia in our interests as well as their own. … The one thing you can be sure of is that the free-wheeling approach of the previous Government is gone forever. We have much to share and much to gain in our trade with the rest of the world. But it must be clear that, in regard to minerals, Australia henceforth intends to be the mistress of her own household.”

A focus of Whitlam’s government was to “buy back the farm”—a strong emphasis on returning Australian resources back into Australian hands. In his 13 November 1972 election speech, Whitlam stated that “in truth, it has not been the ‘farm’ which has been sold—not the industries like wheat or wool or fruit or dairying or gold … It is the strongest and richest of our own industries and services which have been bought up from overseas”, namely, Australia’s natural resources and resource industries.

In a 7 August 1974 parliamentary speech, Connor noted that about 62 per cent of Australian minerals were under foreign ownership or control, and in the case of crude oil and natural gas, this exceeded 70 per cent. The Whitlam government was determined that these figures would not rise, and intended to progressively reduce them, with the objective of 100 per cent Australian ownership in uranium, crude oil, natural gas and black coal. Connor was determined that Australia would move from being primarily an exporter of raw materials, to become a substantial exporter of semi-processed and processed materials. In parliament on 17 October 1974, Connor denounced the current inherited situation of foreign ownership in the resources sector, such as the vast offshore petroleum exploration rights granted over the North-West Shelf of Western Australia, which were held predominantly by an overseas consortium, with only 15 per cent Australian equity. Connor stated that the “total foreign ownership and control of oil and natural gas production, refining and blending within Australia, is over 82 per cent, and policy determinations in respect of the petroleum industry within Australia, have been the subject of decisions by foreign directorates.” Connor and Whitlam consistently emphasised that their objective of Australian ownership would not be achieved by usurping the reasonable interests of overseas organisations, which currently had majority control over much of the sector, but by encouraging and supporting Australian participation. While Australia would be the primary partner in future enterprises, they welcomed continued participation from overseas companies, albeit under appropriate conditions.

The Petroleum and Minerals Authority

The Whitlam government primarily intended to pursue its resources development policies through its flagship institution, the Petroleum and Minerals Authority (PMA). As described by Whitlam at the 1979 inaugural Rex Connor address, “The functions of the PMA were to explore for and develop Australia’s petroleum and mineral resources on Australia’s behalf and to promote Australian ownership and control of those resources through co-operative ventures with private companies. Should an Australian corporation have discovered a lode that appeared to have great potential yet lacked the finance to further explore or develop it, such a corporation would have been able to gain assistance from the PMA rather than from overseas capital. The PMA would also have been able to invite private corporations to participate with it in areas it held in its own right. Like the multinationals, it would have been able to search for and find minerals, extract them, process them and market them, so that it would be one of the few Australian concerns to participate in the highly profitable activities of processing and marketing. Unlike the multinationals, however, it would distribute its benefits to the people of Australia—and that meant all the people, not just a few thousand shareholders.” (Emphasis added.)

The PMA operated under the Minister’s direction and had a high degree of flexibility in how it could perform its legislated functions. It could purchase and lease land and equipment; acquire interests in mining undertakings; and lend money to Australian mining ventures. Although initially capitalised with only $50 million, the PMA could borrow money from banks and the AIDC, which would be guaranteed by Treasury. Connor intended that a major function of the PMA would be to secure future reserves through offshore oil and gas exploration along the Continental Shelf of Western Australia and in areas of the Arafura and Timor Seas. Connor refused to allow multinationals to “farm out” their excessively large exploration permits to other companies, insisting that if the permit-holders did not have the capacity to explore themselves, their permits must be returned to the government.

Opposition to ‘buying back the farm’

The Whitlam government’s visionary resources policies were fiercely opposed from many quarters. Both the Pipeline Authority and the PMA were considered severe threats to the interests of multinational companies and were attacked by industry representatives, including the AMIC.

State governments, threatened by a perceived encroachment upon their collection of state mineral royalties, viciously attacked the PMA. For example, Western Australian Premier Sir Charles Court warned that companies would be refused access to mining tenements if they accepted any form of federal assistance, which dissuaded several companies from participating in proposed joint ventures with the PMA.

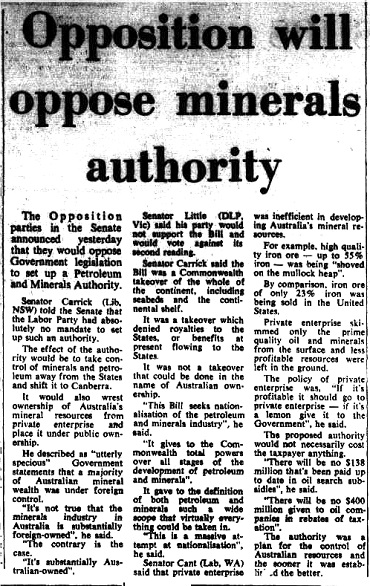

The Opposition Liberal-National Coalition announced that they would oppose the PMA and publicly railed against its establishment, making wild claims that the Whitlam Government intended to socialise the entire industry. Opposition politicians denied the findings of the Fitzgerald report and stridently defended the mining and petroleum sector. The PMA legislation passed the House of Representatives in December 1973, but faced unprecedented obstruction from an Opposition-controlled Senate which was extremely hostile to Whitlam. The Senate was gridlocked over six Labor bills which the Opposition refused to pass, including the PMA Bill, which was only resolved by a double dissolution of both houses of Parliament followed by a general election in May 1974, when Whitlam was re-elected. The PMA Bill was eventually passed in a historic joint sitting of Parliament in August 1974.

Whitlam’s resources policies were also hampered by several court actions, including by the state governments of Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia, which launched legal proceedings against the PMA Bill. In June 1975, the High Court controversially declared the legislation invalid on a procedural technicality, to the glee of State Premiers and the federal Opposition. Notably, three of the judges who ruled against the PMA were members of the secret “brains trust” which would contrive the legal basis upon which Governor-General Sir John Kerr would sack Whitlam several months later; and the fourth judge who ruled against the PMA was a long-time friend of Kerr’s.

Whitlam and Connor emphasised that the PMA Bill was only rejected on procedural, not constitutional, grounds, announcing they would therefore reintroduce the legislation as soon as possible. The Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill 1975 was introduced on 30 October 1975; however, less than two weeks later Kerr ousted Whitlam from government. The PMA was subsequently dismantled by Whitlam’s successor, Liberal PM Malcolm Fraser. (Much later in his life, Malcolm Fraser would express a change in his outlook, including support for what Whitlam had been trying to do.)

Although the PMA was in operation for less than a year, it achieved considerable successes, despite the aforementioned difficulties. It acquired interests in oil and gas reserves of the Cooper Basin; replaced a proposed foreign interest in valuable New South Wales coal reserves; assisted a small exploration company to develop a high-grade copper deposit which would otherwise have been lost; assisted a number of companies involved in oil and gas exploration and mineral development; engaged in a coal exploration program in New South Wales; and was studying procedures and strategy for offshore petroleum exploration and development.

Capital strike

The Whitlam government had determined that it would need to raise $4 billion to fund urgent energy development needs, including a natural gas pipeline; petrochemical plants; uranium plants; the upgrading of export harbours; further development of the Cooper Basin; and electrification of rail facilities. In a 9 July 1975 parliamentary speech, Connor announced that Australia’s proven recoverable reserves of minerals and energy were worth an “astronomical” $5.7 trillion (in 1975 terms!), representing a security ratio of $1,425 in assets for every $1 in proposed borrowing. Connor declared that this was the “best security ever offered to overseas lenders” and slammed the Opposition’s complaints about the size of the proposed loan, saying it was “peanuts” compared with the depth and range of Australia’s resources.

However, the traditional finance centres of Wall Street and the City of London refused to extend credit to the Whitlam government, even though Australia had an excellent credit rating. Connor believed he was facing a capital strike, and blasted the “same international forces and their Opposition puppets which frustrated the early birth of the Australian Industry Development Corporation and which destroyed Prime Minister Gorton [who] now turn their malice, their spleen and their venom on an Australian Government which stands in their path as they seek to enlarge further their grip on Australia’s resources of minerals and energy.” Connor declared that Australia’s offence, “in the eyes of certain international forces”, was borrowing on the credit of Australia, rather than the alternative—which was for those funds to come into Australia as foreign investment and foreign ownership, which Connor said had been “the tragedy of Australia’s development hitherto”.

In late 1974, the Whitlam government decided to pursue funding from oil-producing Middle Eastern countries, which were newly awash with petrodollars in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. This was a funding source which had recently been tapped by the International Monetary Fund and the governments of Japan, France and the United Kingdom. The situation would ultimately spiral into the so-called Loans Affair, in which key figures of the Whitlam government, including Rex Connor, were targeted and publicly discredited in a media storm over alleged impropriety, although no loan was ever obtained and no commissions were paid. Veteran Australian journalist John Pilger has documented that the CIA’s fingerprints were all over the Loans Affair scandal.

Notably, establishment firms of the City of London played a less-publicised role in the Loans Affair. One of the primary figures in the scandal, CIA-linked bankrupt Tirath Khemlani, was introduced to Connor on recommendation of a prestigious London bank and bullion firm, Johnson Matthey, one of the five institutions which set the daily gold price. Johnson Matthey’s glowing recommendation of Khemlani was communicated through the Australian government’s legal advisers in London, Coward Chance & Co., a company whose predecessors had worked for the London Clearing House since its founding in 1888. Coward Chance & Co. also represented the interests of a plethora of major multinational oil companies, including companies in the “Seven Sisters” international oil conglomerate.

Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser used the Loans Affair scandal as justification to block supply in the Senate, intending to force another general election. Governor General John Kerr, who had links to British and American intelligence, used the situation as justification to controversially dismiss Whitlam on 11 November 1975.

Whitlam’s policies obstruct US and Crown commercial interests

The Whitlam government’s determined pursuit of an independent foreign policy, including for greater jurisdiction over US defence facilities which were stationed in Australia, alarmed and angered establishment figures in US government and intelligence circles. In June 1973, US President Richard Nixon appointed “coup-master” Marshall Green as US Ambassador to Australia. Green, a key advisor to US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during the Nixon Administration, was an influential policy planner for Southeast Asia who had been involved in four countries where there were coups, including senior diplomatic postings during USbacked coups in South Korea (1961) and Indonesia (1965).

Declassified diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks reveal that in addition to defence and foreign policy issues, the Whitlam government’s resources and energy policies, including its objective of majority Australian-ownership, were of significant concern to the USA. In a detailed December 1973 report on Whitlam, Green described the prospects for the US government’s three major concerns, listing “exports and investments” as second only to US defence facilities, and before Australia’s foreign policy decisions.

Green and other figures in the US embassy were intensely interested in the Whitlam government’s resources policies, including the progress of the Petroleum and Minerals Authority legislation. The Green-appointed Deputy Ambassador, William Harrop, cabled on 8 August 1974 that of the six bills involved in the Senate gridlock, the PMA Bill was “of greatest importance to US interests”. Green closely monitored Connor’s and Whitlam’s statements on resources policy and foreign investment; collected detailed information on foreign ownership of resources companies and the extent of Australia’s oil reserves; and secretly gathered information from multinational oil companies. Journalist John Pilger describes an incident where a senior Whitlam Minister, Clyde Cameron, was threatened by Green that if the Whitlam government handed over control and ownership of US multinationals to the Australian people, “we would move in”.

Green was closely attuned to American business interests in Australia. Shortly after his arrival, Green met with senior business executives at the Australian American Chamber of Commerce, where he was informed of their concerns about the Whitlam government’s foreign investment and resources policies, and about Connor’s proposed Petroleum and Minerals Authority. Green planned to continue “low-profile” meetings with these business leaders every few weeks. Pilger documented that in early 1974 Green addressed the Australian Institute of Directors, where he essentially incited business leaders to rise up against the Whitlam government, saying that they “could expect help from the United States”, which would be similar to the help “given to South America”—where a CIA-orchestrated coup had occurred in Chile only a few months earlier.

Soon after his arrival, Green paid an “introductory call” to Rex Connor, where Connor confirmed the Whitlam government’s commitment to the policies which Green said “ha[d] greatly disturbed foreign minerals interest in Australia”. Connor “bluntly” informed Green that the level of foreign ownership was excessive and would not be allowed to increase. Connor “strongly reiterated” that “no existing foreign ownership would be disturbed, but all future growth of industry would be under Australian ownership”. Green was clearly cognisant of the value at stake—in his 9 July 1975 parliamentary speech, Connor quoted Green himself saying that, per capita, Australia was the world’s most resources-rich nation.

In July 1974, Nixon ordered a secret review of US policy towards Australia, which inquired into the areas of defence, intelligence-sharing and economic issues, particularly foreign investment prospects. The heavily redacted report documented “disturbing protectionist mutterings” from both sides of politics, saying that “Australia’s great mineral wealth” had inspired Australian “resources diplomacy”. The report profiled key figures of the Whitlam government, including Connor, noting that Connor’s Ministry was responsible for pursuing “Australia’s ownership goals in the energy and minerals industries”. The report determined that the operation of the AIDC, the Pipeline Authority and the PMA would “have a major influence over future foreign investment in Australia”.

In November 1974, Green met with media mogul Rupert Murdoch, who correctly “predicted” that in a year hence, elections would take place in Australia, sparked by refusal of appropriations in the Senate. Notably, Murdoch’s own business interests had been thwarted by Whitlam’s Australian-ownership policies, which impacted a proposed joint venture between Murdoch and BHP to build an alumina refinery. In early 1975, Murdoch ordered his editors to “kill Whitlam”. The subsequent savaging of Whitlam and biased backing of Fraser was so outrageous that journalists from Murdoch-owned The Australian took industrial action against it.

A few months before the Whitlam coup occurred, Green was whisked out of Australia to a plum role in the US State Department.

Considering the intense interest that the documentation shows the US government maintained in Whitlam’s resources and foreign investment policy, it is reasonable to assume that a similar level of interest was maintained by other participants in the Whitlam coup: namely, the British Crown. The Crown has major financial interests in the world’s largest mining and resources companies, better known as the Anglo-Dutch raw materials cartel, including Rio Tinto (then CRA—Conzinc Riotinto Australia), which would have been threatened by the Whitlam government’s attempt to assert national control over Australia’s resources.

Dismantling of Whitlam’s resources policies

After coming to power in a landslide election victory after Whitlam’s ousting, Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser dismantled the Petroleum and Minerals Authority and divested its assets, as part of his election promise to return resources back to the control of the private sector. Fraser retained the Pipeline Authority, although its powers were curtailed; only part of Connor’s pipeline grid was ever completed, and the Authority’s remaining assets were privatised in 1994. Privatisation of the Australian Industry Development Corporation began in 1989 and was completed in 1997.

The Fraser government restored tax subsidies and concessions for mining companies. In 1976, Deputy Liberal Leader Phillip Lynch announced that the Fraser government “firmly believe[d] that foreign capital should play a bigger role than it has in the past three years”, approving large overseas loans for state governments to build infrastructure, intended to entice multinational companies to invest in mining. Although the Fraser government shared Whitlam’s desire to maximise Australian ownership and initially intended to retain 50 per cent Australian ownership provisions, these were gradually watered down to suit the interests of multinational mining companies, to attract further foreign investment.

In the decades since, foreign ownership of Australian mineral resources has only become more pronounced. According to a 2017 report published by the Australia Institute, Undermining our democracy: Foreign corporate influence through the Australian mining lobby, Australia’s mining industry was now 86 per cent foreign-owned. Two companies, BHP Billion (76 per cent foreign-owned) and the Queen’s own Rio Tinto (83 per cent foreign-owned) accounted for 70 per cent of listed mining company resources.

A 2016 Treasury paper on foreign investment in Australia observed that less than 10 per cent of current mining projects were solely owned by Australian companies, while over 90 per cent had some level of foreign ownership. Foreign investment accounted for an 86 per cent share of the ownership of major mining projects (26 per cent from the USA and 27 per cent from the United Kingdom).

In addition, a 2021 investigation by journalist Michael West revealed that over the past decade, the mining industry sold $2.1 trillion worth of Australian resources overseas, but Australian governments received only 9.1 per cent of this sum in taxes and royalties paid. If only considering royalties, the rate fell to 5.6 per cent of the value of the exports. On average, mining companies made a 1,654 per cent revenue mark-up on Australian commodities. West revealed that the mining industry also exaggerated its contribution in royalties. The Minerals Council of Australia (formerly AMIC) commissioned Deloitte to produce a report which supposedly demonstrated the generous contribution which mining companies had made to the Australian economy; however, West discovered large discrepancies in the data, which was exaggerated by an average 19 per cent; and by 33 per cent in previous periods.

Australia’s “great mineral wealth” has been exploited by foreign cartels for many decades, to the great detriment of the Australian people. The Citizens Party has committed to taking up the unfinished work of visionaries such as Whitlam and Connor, to reassert national control of Australia’s vast mineral resources. As part of our mineral resources policy, the ACP will establish a national resources company (p. 16), in the spirit of the Petroleum and Minerals Authority, to develop our strategic resources for the maximum benefit of the Australian people.

By Melissa Harrison, Australian Alert Service, 20 April 2022