With the arrival in Australia of the first consignments of COVID-19 vaccines, the Morrison government is pretending that everything will go more or less back to normal once enough people have been inoculated to achieve herd immunity. The “opposition” Labor Party appears to share the delusion, and has happily returned to the status quo ante of spouting emotive nonsense about “climate change” but failing to differentiate itself from the Liberals in any actually important policy area. A growing number of experts, however, including several former senior military officers, are warning that what is really killing our economy—and our national security along with it—is not COVID-19, but the policy environment in which it emerged. And one such figure, Air Vice Marshall (retired) John Blackburn AO, has dared to lay the blame where it truly belongs, declaring that Australia will remain vulnerable to the slightest external shock unless policymaking is inoculated against the neoliberal “free market” dogma that has plagued both parties for decades.

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic quickly made clear to all and sundry that Australia is far too dependent on imported pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, and manufactured goods generally, as a result of all but a few businesses having “offshored” their operations to countries with cheaper labour. In March 2020 the Morrison government set up a National COVID-19 Coordination Commission (NCCC), chaired by former Fortescue Metals chief executive Neville Power and with former Dow Chemicals chairman Andrew Liveris as special advisor, to identify economic sectors and projects that could begin to remedy such shortcomings, and stimulate a recovery from the inevitable pandemic-induced recession in the process. Despite being beset by many of the same free market axioms whose results it sought to address, the NCCC nonetheless got off to a good start, with Liveris publicly touting the potential for such industries as packaged food, petrochemicals and petroleum refining; and advocating gas price controls to support local manufacturing, and a revival of Australian coastal shipping.1 It soon became clear, though, that on the government’s part the NCCC was all for show. None of its useful recommendations have been implemented, and the government has continued to let the very areas it emphasised most decay more in the meantime, leaving Australia more vulnerable than ever.

Shipping out

The so-called conservative faction of Australia’s de facto one-party political establishment, who have habitually dismissed concerns about the collapse of Australian shipping as little more than a “protectionist” union whinge, are at last beginning to sit up and take notice now that it has become an obvious national-security issue. “Australia is so dependent on foreign shipping that obtaining critical supplies during a national emergency can’t be guaranteed”, lamented neoconservative Iraq War cheerleader Greg Sheridan in the 18 February Australian, citing the remarks of the former Chief of Navy, Vice-Admiral (ret.) Chris Barrett. “Issues around COVID and regional tensions mean that only now we are discovering that we are in a very parlous state”, said Barrett, who is now a board member of cargo industry peak body Maritime Industry Australia Limited (MIAL). “The issue is around resilience to fuel supplies, pharmaceuticals, agricultural equipment, anything that’s critical to society.” MIAL Chief Executive Officer Teresa Lloyd told the Australian that there are now just 13 Australian-flagged or -controlled cargo vessels, down from 100 some 30 years ago. By comparison Britain, which has just over 2.5 times Australia’s population, has 470 such ships. “A national government has legal authority in a crisis to requisition civilian ships which carry its flag or are controlled by its companies, but has no authority over foreign ships”, Sheridan explained. “Thus the lack of a commercial cargo fleet leaves Australia naked in any emergency that interrupts essential supplies.” Former National Party leader John Anderson also chimed in, telling the Australian that the government should “urgently resolve this issue when we see how dangerous the world has become. We need to be sure we have our essential supply lines secured and can bring in critical materials.”

Anderson’s complaint is laughably disingenuous, given he was transport minister in 1998-2005 (and from 1999 deputy prime minister) in the government of PM John Howard, in which capacity he oversaw much of the deregulation and union-busting that destroyed Australian shipping in the first place. Speaking in Parliament on 4 December 2000, Anderson declared that these so-called reforms had been “focused on what is good for Australia”. Explicitly declaring Australia didn’t need its own ships, Anderson proclaimed: “We are not a shipper nation but a shipping nation. We are dependent upon an efficient transport system and efficient wharves” (emphasis added). For the uninitiated: “efficiency” in neoliberal-speak simply means doing everything at the lowest possible monetary cost, regardless of the consequences. And one wonders where Adm. Barrett has been if he is “only now” discovering the “parlous state” of Australia’s supply lines, given his old comrade John Blackburn, initially prompted by concerns about fuel security, has been shouting it from the rooftops for a decade, and raised exactly the same issues with shipping almost exactly a year ago.2 “Ninety-eight per cent by volume of everything we import comes by sea”, he said in a 26 February 2020 interview for the Defence Connect website’s “Insights” podcast. “We only have 14 Australia-flagged ships of 2,000 tonnes or more. Only four are capable of international trade, and none of those can move fuel. … This policy of ‘leave it all to the market, the market can fix it’—essentially what’s happened is that [successive] governments have outsourced our security to the market. To me, that’s crazy.”

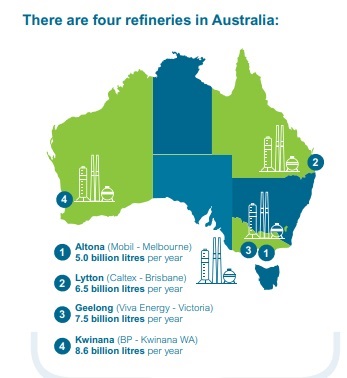

Since then, the Morrison government has allowed fuel security to deteriorate even further, even as it claims to have safeguarded it. Energy Minister Angus Taylor announced to media last March that he and his US counterpart were about to sign a deal that would “[improve] our ability to ensure stocks of critical diesel, petrol and aviation fuel to keep the economy going in the event of disruptions to supply chains” by leasing space in the USA’s 640-million-barrel Strategic Petroleum Reserve—an absurd statement, given that that reserve is stored in underground caverns in Texas and Louisiana! At that time Australia had four remaining fuel refineries; this will soon dwindle to two, and perhaps to only one. BP shut down its Kwinana plant in Western Australia late last year, and is converting it to a fuel import terminal; ExxonMobil earlier this month announced the impending closure of its plant at Altona in Victoria; and Ampol is threatening to do the same with its Lytton refinery in Queensland unless the state and/or federal governments agree to subsidies well in excess of those currently on offer. Viva Energy’s massive Geelong facility is the only one whose immediate future is not in question, and only because it is being propped up by the federal government’s emergency 1 cent per litre “refinery production payment”.

‘Lower cost can come at a very high price’

On the website of John Blackburn Consulting Services Pty Ltd, the business he founded after he retired from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in 2008, Blackburn states that he became interested in the subject of energy security in 2011, when he “realised that the assumptions I had made about energy and fuel supplies when I was the Deputy Chief of the RAAF were fundamentally flawed. … As I now realise, the problem of flawed assumptions is widespread in our society today.” The result is a crisis in what Blackburn terms “national resilience”, an expanded concept of national security which includes not just the needs of the traditional military, intelligence and law-enforcement establishment that (notionally) protects the nation, but also both the productive capacity and the social cohesion of the nation itself. And as he and his coauthors explain in a December 2020 report entitled The Australian Healthcare System: ‘Just in time’ or ‘Just in case’? (the product of a series of workshops with subject area experts and policymakers), the most fundamental of these flawed assumptions is neoliberal economic doctrine.

Rejecting the narrow sector-specific approach that has unfortunately become typical of both scientific and governmental studies in recent decades, Blackburn et al. state at the outset that whilst their report is necessarily framed around the provision of healthcare as such, “it should be acknowledged that supply of goods and services to facilitate equitable access to housing, energy, food and water are fundamental to the health and wellbeing of all Australians, and that focusing on equity is a most effective way of improving public health.” The root of the problem, they write, is that whilst Australia’s healthcare facilities remain world-class, as are the practitioners who staff them, “The principle of ‘equity of access to healthcare for all Australians’ [enshrined in the 1953 National Health Act] has slowly unravelled as inequity more generally has increased across Australian society over recent decades. This decline was not the result of one single policy failure or event, [but] rather a gradual disintegration of Australia’s social contract as the influence of free-market ideology seeped into every aspect of our lives.” (Emphasis added.)

Australia, as should be obvious, sits at the very end of a long and convoluted global supply chain. The result is that with pharmaceuticals just as with fuels, “The ‘just in time’ free market philosophy may have resulted in cost efficiencies, but it has also resulted in significant erosion of healthcare systems resilience as our nation gradually lost manufacturing capacity to the point where we now import more than 90 per cent of our medicines and virtually all of our Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)…. Lower cost can come at a very high price in a crisis.” (Emphasis added.) Moreover the offshoring of the supply of essential medicines was the apparently intended result of deliberate government policies, notably those relating to the pricing structures under the federal Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The PBS is tasked with guaranteeing all Australians access to essential medications; yet in a “reform” in 2007, the report states, “mandatory price reductions were placed upon generic medicines. The subsequent economic pressures on local manufacturers of essential pharmaceutical products resulted in large parts of the industry moving offshore. The federal government analysis of the impacts of this reform completely neglected this outcome and framed their analysis only through a health economics cost-savings lens.” Meanwhile the PBS, the approvals process of medical regulator the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and the pricing regime under Medicare are all being “gamed” by lobbyists for “Big Pharma”, the report says. Most egregiously, according to health professionals this includes “the definition of what is essential in terms of medicines on the PBS … and the process of efficient purchase for greatest health utility”. The authors observe: “This can be seen in the ‘Guaranteeing Access to Medicines’ initiative in the last Federal Budget, where the value that has been articulated by the Health Minister is access to new therapies with no mention of health outcome or cost utility. Despite recent unprecedented national shortages of essential but cheap off-patent medicines, the Federal Budget promised funding [for] extreme-cost new patented medications as a priority.” (Emphasis added.) All of this must be undone, and the entire sector re-regulated, before the crisis can even begin to be addressed.

The one shortcoming of Blackburn et al.’s analysis is that while they categorically reject the axioms of the “free market”, they mistakenly accept that funding for healthcare is necessarily constrained by the exigencies of annual budgets, and that therefore, given the scale of investment required, “it is not practical for Australia to become fully self-reliant”. Whilst that is true in the current policy environment, a revival of public banking in Australia to fund capital works outside the operating budget would free up ample funding to support the properly resourced integrated national health system they envision.

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 24 February 2021

Footnotes