The present Liberal Party government’s obsessive framing of every issue through the lens of national security has made “foreign interference” a watchword. One early manifestation of this obsession is the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme, established in 2018, under which every business or person who acts on behalf of a “foreign principal” in any area even peripherally related to politics and government must register publicly with the Attorney-General’s Department. Targeted primarily at China (though it has in fact failed to find any significant Chinese influence to uproot), the scheme has had the unintended side-effect of exposing the influence operations of our “allies”, notably including the US government’s sponsorship of anti-China propaganda by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. The biggest and most blatant foreign agent in Australia, however, continues to get a free pass—not to mention a Commonwealth salary and a palatial residence at Yarralumla, courtesy of the Australian taxpayer. Decades’ worth of correspondence between Buckingham Palace and various governors-general, made public by the National Archives of Australia (NAA) this month, make clear the true extent to which the vice-regent both keeps the Crown informed of the minutiae of Australian politics, and exerts influence on its behalf. For any who still believed in it, the letters dispel the myth that the queen is “just a figurehead” and make a mockery of Australia’s so-called sovereignty.

In the ordinary course of things, Australian government documents are meant to be published within a legally mandated timeframe unless classified for reasons of national security. Cabinet minutes, for example, are routinely published after 20 years. But despite being official communications between Australia’s head of state and her official representative, letters between the queen (via her private secretary) and the governor-general had by royal decree been deemed “personal and confidential”, and embargoed until after her death—and even then only to be made public with the permission of her reigning successor. In May 2020, however, Melbourne University historian Prof. Jenny Hocking won a four-year legal battle to have the “Palace Letters” of Governor-General Sir John Kerr (in office 1974-77), which prove Kerr did indeed coordinate his 11 November 1975 dismissal of PM Gough Whitlam with the Crown, re-classified as public records and released.1 NAA Director-General David Fricker, a former ASIO officer, stonewalled for six months, however, before finally releasing them in a coordinated media spectacle designed to reinforce the establishment lie that the queen’s hands were clean;2 and as Hocking noted in an 11 November 2021 article for online public policy journal Pearls and Irritations, more than 18 months later the NAA still had not released the letters between the queen and the rest of Australia’s governors-general, to which the ruling equally applied. It has finally done so this month, again handing the scoop to a “safe pair of hands” establishment-friendly journalist in Troy Bramston, a senior writer at The Australian, who once again appears to have been granted privileged access to the letters before they were released to the public, as he and colleague Paul Kelly were to Kerr’s correspondence in 2020. Even so, his writings reveal more than he perhaps intended.

Foreign interference

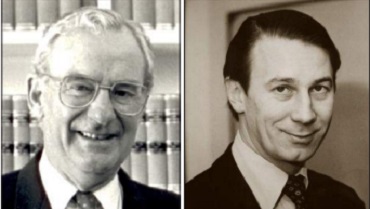

In a series of articles beginning 10 January, Bramston gives examples from the letters of Governors-General Richard Casey (1965-69); Paul Hasluck (1969-74); Zelman Cowan (1977-82, following Kerr); Ninian Stephen (1982-89); and Bill Hayden (1989-96), which in each case illustrate the minute detail the Crown demands, and receives, on the inner workings of Australian politics and government. Their letters include detailed character profiles of current and potential leaders, as well as sometimes scathing criticisms of governments. For example, Bramston recounted that Hasluck in 1972 described PM William McMahon as “without character, devious, a leaker and plotter, and not trusted”, and wrote that his term as PM “weakened the cabinet system, undermined the public service, made public relations exercises even shoddier than usual, lowered respect for the prime ministership, and eroded trust.” (Were he alive today, one could only imagine what he might say of Scott Morrison.)

More importantly, Bramston wrote that “Hasluck’s correspondence, routinely read by the Queen, is far more critical of the Gorton and McMahon governments than Sir John Kerr’s correspondence is about the Whitlam government. … Hasluck, like Kerr, also speculated about his ‘constitutional functions’ and canvassed hypothetical scenarios where he might commission a new prime minister or not grant a requested election during a ‘constitutional crisis’” (emphasis added). Such musings were reportedly “welcomed and encouraged” by the Palace. Elsewhere, Bramston states—and repeats with but slight variation in several of his articles— that “Academics who say Kerr’s letters breached protocol and convention, and were remarkably different to his predecessors’ and successors’ because they canvassed political matters, are mistaken. Indeed, [the queen’s Private Secretary Philip] Moore told Cowen in July 1982 his political assessments were ‘invaluable to the Queen’.” To Bramston, this is evidence that the Crown would have had no inkling that the Whitlam dismissal was in the works. The less benign—and therefore, given the well known character of the British establishment, far more credible—interpretation is that the Crown is and has always been on high alert for anything happening in Australia that might threaten its interests or agenda, and prepared to act accordingly.

Adding to this impression is Bramston’s revelation that in the early 1990s, when then-PM Paul Keating “launched his crusade to become a republic”, Governor-General Bill Hayden, a former Labor Party leader who had been foreign minister under previous PM Bob Hawke, “whose appointment as governor-general was controversial because of his party’s republican sympathies, advised Buckingham Palace on how to counter republicanism. ‘If you would wish me to explore some implications of this matter, for instance, with some suggestions on what might be done in response to this trend, I would be happy to bring forward some suggestions’, Mr Hayden wrote in July 1991. Sir Robert Fellowes, the Queen’s private secretary, said the monarch would be grateful for the advice.” And here we are told that queen is “above politics”? Hardly.

The level of candour in these dispatches comes about only because, as Hayden was reportedly told in his final letter from Buckingham Palace, it was expected they “[would] not be revealed for many, many years hence, unless it be to the Queen’s own official biographer some years after her death.” Presumably the current vice-regent will be more circumspect; though in these days of encrypted email and selfdestructing data files, perhaps not. In any case, even establishment gatekeeper Bramston could not help but complain that in contrast to Kerr’s papers, which were released in full to the public, “Sentences, paragraphs or full pages have been redacted throughout the correspondence [of the other governors-general] by the National Archives”, which goes against the “spirit of pro-disclosure” the NAA espouses—not to mention the ruling of the High Court. This is made all the more suspicious by the fact that whilst Bramston describes some of the redactions as “absurdly comical in what they try to conceal from Australians”, the NAA has also “made excessive redactions to the Cowen and Moore letters that deal with policy matters and relate to the 1975 dismissal. This is despite the letters being official records and almost all at least 40 years old.” (Emphasis added.)

In other words, royal prerogative still reigns supreme so far as the NAA and its “former” intelligence officer director are concerned; the cover-up continues, and the ruling of Australia’s highest court be damned.

Footnotes

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 19 January 2022