7 Dec.—Four years after the end of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), the Australian-led peacekeeping mission launched in 2003 to halt that country’s de facto civil war known as “the Tensions”, Australian Federal Police and Defence Force personnel have once again been deployed there at the government’s request after riots erupted in the capital city Honiara on 24 November. Whilst it is thus far unclear exactly who and what is responsible for setting off the renewed violence, what is clear is that much of the blame for its underlying causes lies with Canberra. Acting on behalf of the British Empire and more recently its informal Anglo-American successor, Australia has worked for decades to ensure its fellow “former” Pacific colonies do not adopt sovereign foreign policies which undermine imperial geopolitical agendas, and has denied them the development necessary to sustain lasting peace and stability in the process. The recent focus of these efforts, formalised in the Turnbull Liberal government’s “Pacific Step-Up” strategy in 2016, has been to prevent our Pacific Island neighbours from developing relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and especially from joining its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) international development program. And since Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan (formally the Republic of China, ROC) to Beijing and joined the BRI two years ago, Taiwan and the USA have been working openly with local political forces to destabilise his government.

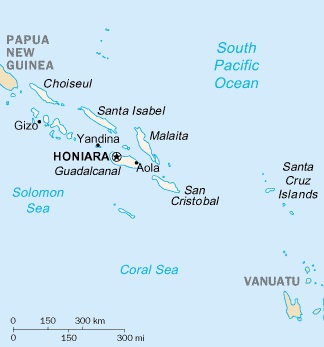

Solomon Islands, which lies on the Pacific Rim east of Papua New Guinea, is a “former” British colony which was ruled directly by a British governor until 1978, and thereafter run (like Australia) as a constitutional monarchy. Britain had established diplomatic relations with the PRC in March 1972, followed by Australia that December, and the USA in January 1979. But any moves by the Pacific Islands nations to do the same—which Australian media ridiculously portray as a declaration of “allegiance” to Beijing, rather than merely the much belated recognition that the ROC government lost China’s civil war in 1949 and does not run the country anymore— has always been met with hostility by the USA and Australia, which prefer to keep them as an aid-dependent “buffer zone” against the encroachment of so-called Chinese influence. For example, after Sogavare (during a previous stint as PM) signed a contract with Chinese electronics manufacturer Huawei in January 2017 to build a modern telecommunications network that would connect the nation’s far-flung provinces to Honiara, and thence to Sydney by way of Papua New Guinea via a 4,000 km undersea fibre-optic cable, the Australian government and security services launched a scare campaign about the “security threat” supposedly posed by Huawei. When that failed, Australian PM Malcolm Turnbull in January 2018 offered Sogavare’s successor Rick Houenipwela a deal reminiscent of a mafia protection racket: ditch Huawei, and Australia would fund two thirds of the project (about $200 million) out of its aid budget; refuse, and Canberra would veto the connection to Sydney on “national security” grounds, rendering the whole project pointless.1

Taiwan ‘completely useless’

According to Sogavare, who has served four non-consecutive terms as PM in 2000-01, 2006-07, 2014-17 and from April 2019 to the present, such Australian interference in Solomon Islands affairs is a longstanding problem, which in part motivated him to recognise the PRC. Whereas his detractors nowadays paint him as a puppet of Beijing, in fact Sogavare had previously been “a long-time advocate of the Taiwan relationship”, the Australian newspaper acknowledged in an 11 September 2019 article, five days before he formally announced the switch. In an interview with Australian National University (ANU) China scholar Dr Graeme Smith, Sogavare described how he had come to realise that his nation’s interests would be better served by establishing relations with the PRC because “unlike Taiwan, China would be able to provide support without having to defer to Australia”, the Australian reported. “To be honest, when it comes to economics and politics, Taiwan is completely useless to us”, Sogavare said. For example, in 2006, during the early phase of RAMSI, “I sent 40 police officers to go and train in Taiwan”, he recalled. “And you know what Australia did? The Foreign Affairs Minister himself went to Taiwan and says: ‘Stop the training, that area is ours.’ So what I’m saying is, if this was China … they wouldn’t give a damn to Alexander Downer if he goes there and says: ‘You stop, get out of here.’ They’d say: ‘Get the hell out of here.’ This is a sovereign decision made by a sovereign government.”

Australia has kept its nose clean, at least publicly, since Sogavare made the switch (which was ratified by Parliament, not a unilateral decision as some have claimed), and signed Solomon Islands up to the BRI the following month. Not so the USA, which immediately began bypassing Honiara and proffering aid directly to the eastern province of Malaita— home to the separatist militias whose clashes with counterparts on the “main island” of Guadalcanal (and with the national police) precipitated RAMSI—and its separatist, pro-Taiwan Premier Daniel Suidani. On one occasion, the US State Department transferred $35 million to Malaita after Suidani cited the Sogavare government’s China policy to demand an independence referendum.

Suidani is also on Taiwan’s payroll. Having “pledged to refuse any Chinese investment in his province while fostering a close partnership with Taiwan”, Al Jazeera reported 8 June this year, he had personally accepted financial and material aid in exchange for continuing to “recognise” Taipei over Beijing. “Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic”, Al Jazeera reported, Suidani “held numerous public events celebrating the arrival of Taiwanese aid consignments … [which were] not approved by Honiara. The consignments began flowing after a clandestine meeting between [Suidani’s senior advisor Celsus] Talifilu and Taiwanese diplomats in Brisbane, Australia in March last year and have often been unveiled in ceremonies with prominent displays of the Taiwanese and Malaitan flags.” (Emphasis added.) In May this year Suidani even politicised his own personal health crisis by accusing Sogavare of attempting to blackmail him into toeing the line on China by threatening to withhold funding for treatment for a brain tumour—then making a show of travelling to Taiwan for treatment at the ROC government’s expense.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that most of the rioters who on 24-25 November first tried to storm Parliament and depose Sogavare, then set fire to businesses owned by Honiara’s Chinese diaspora community, a police station, and other government buildings, were reportedly Malaitans. “I feel sorry for my people in Malaita because they are fed with false and deliberate lies about the switch”, Sogavare told the ABC in a 26 November interview. “That’s the only issue” behind the riots, he said, “and unfortunately, it is influenced and encouraged by other powers … that don’t want ties with the [PRC], and are discouraging Solomon Islands to enter into diplomatic relations and to comply with international law and the United Nations resolution [that transferred China’s UN seat from the ROC to the PRC in 1971].” He declined to name names, saying only: “We know who they are.” Interestingly, however, Sogavare blamed not Suidani but opposition leader Mathew Wale—who cited the riots as evidence that Sogavare had “lost control” of the country and should resign—for instigating the violence. “That guy is right behind all that is happening … he encouraged the people of Malaita to come over to Honiara to disturb our Parliament”, Sogavare said, adding: “He is wasting his time … what he is advancing is totally undemocratic.”

True to his word, Sogavare on 6 December comfortably defeated a motion of no confidence in his government. Meanwhile, as of this writing the Australian personnel whose assistance Sogavare requested under the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) he signed with Turnbull in 2017 to replace RAMSI, hoping never to need it, have succeeded in restoring order, although protests continue, and tensions may yet flare once again. Amongst all the uncertainties, at least one thing is sure: even had Canberra the purest of intentions, it lacks the capacity to help Solomon Islands achieve the kind of lasting peace that only comes with development and prosperity. It would better serve the interests of all (legitimately) concerned by minding its own business, and telling its “allies” to do the same.

Footnotes

1. “Pacific ‘security fears’ over China are made in Canberra”, AAS, 20 June 2018.

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 8 December 2021