In April this year, Britain’s global banking giant HSBC proceeded to close 82 bank branches in the United Kingdom, over and above the closures it made last year. Other major British banks including Barclays, NatWest, Lloyds, Co-op Bank and TSB Bank also closed many branches. Over the past five years around 55 bank branches have closed per month, leaving many towns without a bank.

British bank conduct watchdog the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) had instructed banks to hold off on closures during COVID-19 lockdowns to minimise the impact on vulnerable customers, many of whom depend on day-to-day use of cash. A February 2020 independent “Access to Cash” review, which followed up on an initial 2019 report, had warned that the cash system was already at a “tipping-point” and would collapse without legislative intervention. Still, more than 800 bank branches were closed since the beginning of 2020.

The Access to Cash review indicated that the matter was being taken seriously, but that all initiatives to address the issue were thus far voluntary. It reported that the three main regulators, the FCA, Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) and Bank of England (BoE), had formed a joint working group called the Joint Authorities Cash Strategy Group (JACSG) “to explore the issues around reducing levels of cash”. But the situation continued to worsen.

In its 2020 budget, the British Treasury announced it would prepare legislation to protect cash access. In a section on “Supporting the most vulnerable”, it stated: “The Budget announces that the government will bring forward legislation to protect access to cash and ensure that the UK’s cash infrastructure is sustainable in the long-term.” In October that year, it issued a “Call for Evidence”.

The Financial Services Act 2021, passed in April, ushered in changes that allowed people to withdraw cash at shops and businesses without making a purchase (known as “cashback”), but motion on the broader legislation promised by Treasury is slow. It is aimed at “establishing geographic requirements for the provision of cash withdrawal and deposit facilities, the designation of firms for meeting these requirements, and establishing further regulatory oversight of cash service provision.” Treasury launched a consultation starting 1 July 2021, which will close in September.

Treasury’s “solution” would seem only to uphold the hotchpotch existing network of banks, businesses and post offices that currently provide cash access, giving the FCA the power to prevent the shutdown of certain bank branches where alternatives are lacking. An expansion of banking could easily be achieved by returning to the UK’s strong tradition of public postal banking. Even the limited Treasury proposal has raised the ire of free marketers, however, with various voices raised against “new powers” for the FCA to force banks to keep branches open. It has even prompted some to observe that a national bank would achieve the desired result!

According to British press reports, the proposal has “spooked bankers” who do not want to be held to “rigid legislation”, including suggestion that banks may take legal action if the new rules are introduced. One headline, in the 15 August Telegraph read, “Banks must be allowed to close branches”, with the kicker: “It shouldn’t be any business of the FCA or the Treasury whether banks choose to keep branches open”! British financial journalist Matthew Lynn argued that we don’t force any other commercial business to stay open (such as book or wine purveyors), nor should we force banks to retain unviable branches.

The move to digital banking has made a big impact, he said, but it’s about to get worse: “Apple has moved into payment systems, Amazon has a checking account along with a range of other financial products, and Facebook has even toyed with launching its own currency.”

We must allow the banks to be focused on profit and the nation focused “on building a world-beating finance industry”, Lynn insisted, but then added the following: “There is a case for preserving access to cash, and to a range of basic services for anyone who still doesn’t have a smartphone, even if it is often overstated. But if we need to do that there is a far better way. We should simply create a National Bank, tasked with providing cash machines across the country, and places where you can deposit notes and coins, and process cheques if you happen to still remember what they are (rather like the old Girobank that was sold off way back in 1989).” Girobank was a public sector bank established by the British Post Office in 1968, under the Harold Wilson government. It had become the nation’s sixth-largest bank before it was privatised.

Financial exclusion

Talking to the Sunday Telegraph on 15 August, Gareth Shaw, head of money at consumer choice agency Which?, referenced the existing access standard that banks are supposed to follow, saying it is “not worth the paper it’s written on”. He could not cite a single case of a bank reversing a branch closure decision after holding the consultations they are obliged to hold with local communities. Even with the natural shift to a digital economy, he specified, the transition should not be “dictated by market forces” alone, but by “oversight from the Government and regulators”.

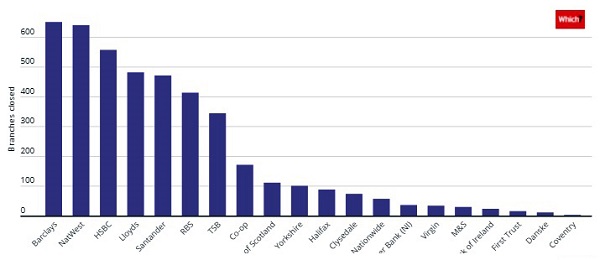

Pointing to increasing financial exclusion and reduced access to cash, Which? had reported in 2018 that “The UK has lost almost two-thirds of its bank branch network in the past 30 years, leaving a fifth of households more than three kilometres from their nearest current account provider.”

Mapping network data from all bank service providers, Which? showed a decline from 20,583 outlets thirty years ago, to only 7,586 in 2018. Other measures reflect the shocking lack of bank access. A “Community Request an ATM” initiative led to 3,000 requests for ATMs. A trading community website warned banks would disappear from shopping strips by 2032 if shutdowns continued at the current rate. Not surprisingly, the poorest, most vulnerable residents and those who can’t travel or access digital services, are hardest hit. A 2018 survey found that 86 per cent of respondents had visited a bank branch at least once in the last year; 77 per cent demanded bank branches in case of technical disruption.

In a statement that will ring true for many Australians, one bank customer told Which?: “While post offices meet the need for access to cash—a need that online banking doesn’t meet— other transactions can’t be undertaken there. … It’s nonsense to claim that people don’t need branches anymore. Despite its sentimental radio and TV ads, I feel my bank doesn’t really care about its customers. Many of us feel that our loyalty has been for too long taken for granted and are taking our hard-earned savings elsewhere.”

The Post Office

London business newspaper City A.M. reported new data on 10 August that revealed the highest monthly cash volume ever was withdrawn from Post Offices in July 2021. Said Martin Kearsley, banking director at the Post Office: “As some banks continue to close branches, either permanently or in response to staff shortages during the pandemic, Post Offices are ‘the last counter in town’ in many places across the country.” But Post Offices across the nation are facing a tough job just to stay open.

There are 11,500 post offices run as private businesses. In 2012 the Post Office was separated from the Royal Mail (which does the actual delivery), making them mere retail agencies for stamps, parcel collection for Royal Mail, broadband access and financial services.

Since 2017 basic banking services have been provided by the Post Office, by paid arrangement with banks, including withdrawal of money, checking account balances and cash or check payments. This is not the same as public postal banking, as customers cannot transfer money or consult on accounts, credit cards, loans or mortgages, conduct an anti-fraud check or transact legal documents. Many people prefer to deal directly with their bank, are concerned about lack of privacy at a post office counter, or require the assistance of staff with financial expertise. (Many post offices are now situated within other retailers such as newsagencies or convenience stores.)

In 2019 Barclays announced it would stop utilising the Post Office for its banking services, but reversed its decision under public pressure, signing up to a further three-year term. Other banks have opted to provide periodic service at mobile banking vans, instead of retaining branches. Another makeshift solution is branch sharing, including community banking hubs that can be used by customers of all major banks, often combined with the local Post Office.

By law, post offices must be within three miles of 99 per cent of their customers, but temporary closures or cutbacks in opening hours, particularly in rural areas, have climbed steeply since 2017. Results of a 2019 survey revealed the risk of thousands of branch closures over coming years as increasing financial pressure impinged on Post Office owners. Government subsidies for Post Office operators are subject to an upcoming 2021 comprehensive spending review.

In mid-2019 one small-town Post Office owner observed: “I’m taking all the risk on behalf of the banks, getting a pittance for it and the government is quite happy announcing that the Post Office is taking the slack”, according to the Financial Times of 20 May 2019. “We can’t carry on the way it is—something needs to be done.”

Post Office owners are desperate for alternative sources of income. The National Federation of Sub-Postmasters is calling for a greater range of government services and banking to be provided at the Post Office. According to the Independent of 20 May 2019, the organisation says its 8,000 members feel “disenfranchised, marginalised and relegated to the bottom of the food chain”.

Public postal banking would drive renewal of the postal service. The UK operated the world’s first Post Office Savings Bank, running from 1861 to 1969. At that time Treasury took it over, transforming it into National Savings and Investments, which takes savings to this day but does not offer any other banking services, such as current operating accounts, credit cards or mortgages.

Wales welcomes community bank

On 22 March the Welsh government announced progress towards launching the Community Bank of Wales, known as Banc Cambria.

Referencing the UK’s move to introduce legislation to protect cash access (main article), the statement said the UK Government “simply hasn’t acted fast enough on its intentions—one year on and there is still no clear timetable for its introduction”. Fault lines within the financial system demand urgent action to provide adequate access to banking and finance for the economy, vital for the “post pandemic recovery”. Yet consumers are still facing declining numbers of bank branches and ATMs—nowhere in the UK worse than Wales.

The new bank, originally proposed by the Peoples Bank for Wales Action Group in 2016, will be “owned by its members, taking account of local community needs, preventing capital drain, maintaining access to face-to-face banking and driven by customers’ needs, rather than profit maximisation”.

The statement cites growing efforts to establish regional Community Banks in other parts of the UK, supported by the Community Savings Bank Association. Pending regulatory approval, the Welsh government hopes to obtain a banking licence from the Prudential Regulatory Authority by the (Northern Hemisphere) Autumn and thirty bank branches are planned.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 25 August 2021