13 May—The worsening social and economic crisis in Western Australia, brought on by the collapsing housing bubble, is a foretaste of what awaits the eastern states on a far larger scale unless governments intervene to prevent an economic crisis that is shaping up to be at least as bad as that of the 1890s, and probably worse.

Nationally, the housing bubble is of course centred upon Sydney and Melbourne, which between them comprise about 40 per cent of Australia’s population and 60 per cent of total housing “value”. Perth has a population of just over two million, and therefore its property prices have less direct impact on the national economy and banking system; but it is nonetheless highly significant, for two related reasons. First, the WA economy—heavily dependent on mining, with an outsized services sector concentrated in the capital city, while vital primary production is strangled by usury and bad public policy—is a microcosm of Australia’s as a whole. Secondly, the so-called “mining boom” allowed the banks to inflate the local Perth mortgage bubble much faster, but by otherwise identical methods, than in the eastern capitals; and the subsequent mining “bust” pricked it much sooner, in June 2014, versus November 2017 in Sydney and January 2018 in Melbourne. Therefore, at least so far as the mortgage bubble is concerned, where Perth goes Australia will likely follow.

In addition to the federal government’s hare-brained scheme to bring deposits down to five per cent for first home buyers (p. 3), sundry pundits and property sector insiders around the country have likewise been trying lately to breathe new life into the bubble, hoping to suck in new buyers with the promise that the market is near its floor and price rises are just around the corner. The 26 April West Australian, for example, cited figures from property analyst Terry Ryder of hotspotting.com.au, according to whom the Perth market is well on the way to recovery, with median house prices having risen over the past year in 85 of its 216 suburbs—one, upmarket Mt Pleasant, by a whopping 26 per cent, followed by Brabham (21 per cent); Kensington (19 per cent); Claremont (18 per cent); and West Perth (16 per cent). Even if accurate, however, these surges amount only to froth at the edges of the imploding bubble, since evidently there has been no overall recovery: as Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) principal Martin North noted in an 11 May video, the latest figures from leading real estate data firm CoreLogic show Perth house prices down 8.3 per cent year-on-year (1.9 per cent of that just in the last quarter), and 18.5 per cent from their peak.

Blacklisted

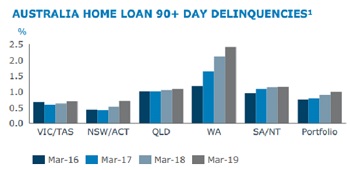

Like the other capital cities, Perth is host to a glut of overpriced suburban homes sold at the height of the bubble, whose owners now find themselves in “negative equity”, where the house is worth less than the outstanding mortgage. Indeed, those who took out interest-only (IO) loans, either out of desperation or intending to “flip” their properties for capital gains, still owe the full, bubble-inflated price of five or more years ago. Now that the banks have been forced to apply something approaching proper lending standards, many of these people no longer qualify for large mortgages and thus are unable to re-finance, especially in cases where falling prices have pushed loan-to-value ratios (LVRs) towards or even beyond 100 per cent, versus a generally acceptable limit of 80 per cent. Nor can many afford the 40 per cent jump in their monthly repayments when their mortgages reset to principal-plus-interest (P+I) at the expiry of the IO period, typically three to five years but which the banks in most instances were previously happy to renew. As a result, forced sales, delinquencies, defaults and foreclosures have skyrocketed. ABC News on 9 May cited as typical the case of a Perth woman who had had to sell her investment property because she and her husband could not afford the $900-a-month increase in repayments upon the switch P+I. “I’ve always been able to roll over my interest-only term when that expires … and now they’ve said, ‘You can’t do that anymore’”, she said. “This is not something I want to sell, I’ve had this property for 10 years. I’m selling because I have to.”

Citing analysis by DFA, ABC reported that in addition to the across-the-board tightening of lending criteria in the wake of the royal commission, “data obtained by the ABC shows … [that banks have created] a so-called ‘blacklist’ of areas where location is deemed more of a liability to people seeking a loan. … In the higher-risk suburbs, banks have applied tighter lending criteria and required borrowers to find larger deposits to avoid paying costly mortgage insurance on top of their loans. Perth is the capital city that tops the nation for the riskiest suburbs, and regional Western Australia is also home to the vast majority of blacklisted postcodes.” Topping the national list are regional centres Newdegate, Bodallin and Pithara, farming communities that have been smashed by decades of ruinous deregulation and “free trade”; production-busting environmental policy; and predatory banking operations, most notably by CBA after its takeover of Bankwest in 2008 and ANZ through its acquisition of Landmark’s loan book in 2009, both of which saw scores of farms and other businesses foreclosed upon despite having never missed a payment.

Perth’s highest-risk suburb is Ellenbrook, a satellite city some 25 km northeast of the CBD. Martin North told AAS that according to his modelling—which is based on the latest official government data, plus the results of DFA’s own rolling 52,000-household survey—63 per cent or around 10,000 of Ellenbrook’s households have a mortgage, compared to a WA average of 39 per cent, and 34 per cent nationally. Residents are relatively high earners, with a median weekly household income of $1,689, compared with $1,210 in WA and $1,203 nationwide; but a $2,167 average monthly mortgage payment means 17.8 per cent of the suburb’s borrowing households pay more than 30 per cent of their income to service their housing debt, versus a WA average of 8.6 per cent, and 7.2 per cent nationally. Of the 10,000 indebted households, North said, 3,500 (35 per cent) are in mortgage stress—i.e. struggling or unable to meet their repayments from current cashflow—and 255 are at risk of default in the next 12 months. A local source told AAS that already, one in five houses for sale in Ellenbrook are listed as “mortgagee in possession”, meaning they have already been repossessed by the bank. Negative equity has likely been a major factor, as Ellenbrook’s average house price is down 24 per cent since 2014, well ahead of Perth’s overall 18.5 per cent collapse.

Ellenbrook is by no means an isolated case, merely the worst of a bad lot. North’s analysis for ABC showed a half-dozen other suburbs in close to the same shape, and a slew of others not far behind. And WA sources have told AAS that the fallout from the bursting bubble, state-wide, is much worse than the national or even local media are letting on. Perth’s middle-ring and outer suburbs, they say, are dotted with tracts of brand-new houses standing apparently vacant and unsold. The market is dead in the regions, too—in Albany on the south coast (population around 35,000), there are over 1,000 houses for sale and almost no takers, despite some vendors having cut their asking prices in half. The Perth service and retail sectors have been hit hard, leaving malls and shopping strips suddenly full of empty shops. Despair is taking its toll, with suicide rates at their highest in 20 years and still climbing.

The Labor Party state government’s only policy response thus far has been to beg bank regulator APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) to wind back its loan serviceability benchmark—the interest rate at which prospective borrowers must be able to service their loans—from 7 per cent to 6.75 per cent, as APRA and the Reserve Bank are reportedly considering in lieu of the RBA cutting its cash rate from an already record-low 1.5 per cent. According to the 6 May Western Australian, Treasurer Ben Wyatt complained to APRA that the 7 per cent buffer was “restricting access to finance” (exactly as it is meant to do!), and thus “retarding a recovery”. Relaxing the benchmark, Wyatt wrote, would “deliver important benefits to the WA property market”. (If, that is, perennially inflated house prices are a “benefit”; so much for Labor’s pretended desire to improve housing affordability.) Like the federal government’s home deposit guarantee scheme, this may slow the collapse of the housing bubble, though not for long—but only at the expense of saddling Australians with even more unpayable debt, dragging out their misery, and making the crash even worse when it inevitably happens. Instead, Wyatt should lobby the federal authorities for a foreclosure moratorium to keep people from being put out in the street when they default on their mortgages; and the passage of the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill currently before the Senate, to eliminate the predatory lending that blew the bubble in the first place.