The damage bill from the recent floods which have devastated New South Wales and Queensland is expected to exceed $2 billion. Although natural disasters are a regular occurrence in Australia, for decades successive governments have failed to implement effective mitigation strategies, particularly in regard to flood risk management. Local councils and the community bear the brunt of these policy failures.

The Productivity Commission’s 2014 report, Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements, acknowledged that Australia “has a long history of climate variability and extreme weather events … Natural disasters are an inherent part of the Australian landscape.” The Commission observed that just 10 per cent of natural disasters accounted for 80 per cent of insurance losses, which implied that natural disaster policy needed to be well-designed to deal with these “infrequent but costly” natural disasters.

The report found Australia’s natural disaster funding arrangements were “prone to cost shifting, ad hoc responses and short-term political opportunism”. The Commission acknowledged the longstanding concern that “[g]overnments overinvest in post-disaster reconstruction and underinvest in mitigation that would limit the impact of natural disasters in the first place”, leading to higher overall costs to the community.

The Commission observed that “government action is not always in the best interests of the community … Research shows that natural disaster policy is beset by political opportunism and short-sightedness (myopia), which biases how funding is allocated to natural disaster risk management. Politicians can be quick to provide generous post-disaster assistance, which provides immediate, observable and private benefits to individuals and has strong political salience. By contrast, the political incentives for mitigation are weak, since mitigation provides public benefits that accrue over a long time horizon.”

Natural disaster spending

Australia spends only 3 per cent of its natural disaster funding on mitigation and prevention, while 97 per cent goes to recovery after the event, which can amount to billions of dollars in government spending. There are often catastrophic costs to the wider community. For example, in 2015, the total economic cost of natural disasters exceeded $9 billion (0.6 per cent of gross domestic product). The social costs were found to be equal, if not greater, than the physical costs.1 Much of these costs could be prevented by mitigation: the Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2017 Interim Report, published by the US National Institute of Building Sciences, found that every $1 spent on hazard mitigation could save a nation $6 in future natural disaster costs.

Although natural disasters occur regularly in Australia, the Australian Government does not provision for future national disasters in the budget, although such provisioning was made in the past. The Productivity Commission asserted that this “creates a systematic bias in favour of recovery expenditure and against mitigation and insurance, and has seen natural disaster costs become a volatile and growing unfunded liability for government”. The Productivity Commission’s report recommended a major restructuring of Australia’s natural disaster funding arrangements; however, Floodplains Management Australia (FMA), the national peak body representing flood risk practitioners, said the government’s response to the inquiry “[left] much to be desired”.

These insights are revealing, not least because the Productivity Commission is itself a bastion of the neoliberal economic ideology that usually argues against most government investment, on narrow cost-benefit grounds. However, its recommendations also left a lot to be desired. Firstly, the Productivity Commission recommended increasing federal mitigation funding by an additional $200 million a year, which was too small, and which the government did not implement anyway. Second, the Commission concurrently recommended that post-disaster recovery funding to states should be reduced—to “sharpen incentives” for states to mitigate and insure against risks. This was even though the Commission had acknowledged that the problematic funding model of the federal government’s Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) had restricted state governments and local councils from spending properly on mitigation, a decades-long problem which persists today in the NDRRA’s successor organisation, the 2018 Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements (DRFA).

The Australian Government’s dysfunctional natural disaster funding policies have persisted. In 2019, the Morrison Government established the $4 billion Emergency Response Fund (ERF), which could draw up to $200 million per year for disaster resilience or post-disaster support initiatives. However, although the Fund has earned over $800 million in interest in its four years of operation, until very recently it had not allocated any funding.

In response to the 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, which was initiated as a result of the devastating 2019-20 bushfire season, the Morrison Government released $50 million for flood mitigation projects under the ERF’s new National Flood Mitigation Infrastructure scheme. This fell far short of the total $217 million in flood mitigation funding requested by state governments in 2020. As reported by ABC on 7 March 2022, state governments have raised concerns over the ERF’s slow rate of funds release; the opaque nature of the approval process; and a lack of consultation with the states, including instances where projects, which were identified as a critical priority by state governments, were passed over in favour of non-priority projects. During the recent flood crisis in Queensland and NSW, which resulted in media criticism over the lack of funding released by the ERF, another two rounds of $50 million were announced for flood mitigation.

In response to another Royal Commission recommendation, the Morrison government announced the “Preparing Australia Program” (PAP) in May 2021, which would allocate $600 million over six years for disaster resilience projects. However, a full third of that funding is allocated to increase the resilience of private residences, in collaboration with the insurance sector. Notably, details of this project have been postponed because of a spike in the price of construction materials. Additionally, the PAP’s maximum project allocation is $10 million, which is inadequate for essential projects like Queensland’s $14 million upgrade to its Flood Warning Infrastructure Network, which was denied funding in 2020 under the aforementioned ERF, despite being identified as a priority project. The PAP scheme has also recently come under fire because it designates some local government areas as priorities for funding, while inexplicably ignoring others, such as Lismore in NSW, which was not deemed a priority for funding despite being one of the most floodprone areas in Australia.

Local governments under water

Although funding costs are shared with the federal government, Australia’s constitution stipulates that the states and territories are responsible for managing natural disaster risks. However, state governments delegate much of this responsibility to local governments.

This has resulted in significant pressure on local councils, which was recognised by the 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements. The Commission recommended that state governments should take responsibility for ensuring that local governments had adequate resources to meet these delegated responsibilities; and recommended that state governments review their resource-sharing arrangements with local governments.

Although the design of the 2018 Disaster Recovery Funding Arrangements (DRFA) was purported to relieve the financial burden on councils, many have opted out of the new cofunding arrangements, because they would actually be financially worse off. In its submission to the Royal Commission, Floodplains Management Australia (FMA) stated that “[t]he requirement for matched funding contributions from Local Governments is a major concern for many Councils which have limited financial capacity to meet increased funding obligations. There is a need for flexibility for projects with a significant cost-benefit ratio to be funded without matching Local Government funding”.

In a 22 March 2021 media statement titled, “How long must we wait for effective flood protection?”, FMA President, civil engineer Ian Dinham, lamented that every time Australia has a natural disaster, we “rely on the SES [State Emergency Service] to solve our problems instead of preparing for such events with better investment in preventative measures … each time the disaster subsides it is then up to the local councils to deal with the recovery and clean up at the expense of our local communities.” In 2017, Dinham stated that “local Councils are the lowest level of Government and the least able to afford to maintain their assets, let alone fix them after natural disasters.” In 2016, Dinham observed that an increasing number of essential post-flood activities had become ineligible for funding. Dinham described long delays in the approvals process, which involved excessive red tape: councils were required to engage costly private consultants and external contractors to be eligible for funding the reconstruction of vital infrastructure.

Flood risk management

The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience’s Managing the Floodplain: A Guide to Best Practice in Flood Risk Management in Australia, documents that although deaths have declined, the economic damage caused by floods has grown as a result of increasing population growth and development of floodplains. It is estimated that the total economic exposure of communities to flooding is approximately $100 billion. The 2011 Queensland floods were estimated to have temporarily depressed gross domestic product growth by up to 1 per cent. A comprehensive December 2020 report, Flood Risk Management in Australia, produced by a global insurance group, the Geneva Association, documented that approximately 7 per cent of all Australian households have flood risk, with 2.8 per cent located in high-risk areas.

Although flooding is Australia’s costliest natural disaster, according to FMA, floods are the most manageable of all natural disasters.

However, FMA President Ian Dinham has called Australia’s flood mitigation “laughable”. In an 11 April 2017 interview with ABC, Dinham compared Australia’s spending on flood management, which disproportionately funds recovery over mitigation, with the Netherlands, which spends 97 per cent of funding on flood mitigation and only 3 per cent on recovery—the polar opposite of Australia’s approach!

As documented in the Geneva Association report, funding for flood risk management is dependent on grant funding to local councils, which is not necessarily allocated to high-risk areas. For example, the provision of flood warning systems is largely dependent on government grant funding and funding contributed from local councils. This results in inconsistent implementation of flood warning systems around Australia, and warning systems are not necessarily implemented in high-risk communities which are prone to flash flooding.

Unfortunately, most local councils don’t have sufficient resources to allocate to flood risk management, or to hire specialised staff. The responsibility for flood mapping, which provides information about the possibility of flooding in an area, including historical flood mapping, has been delegated to local councils. However, funding gaps have led to inconsistent flood risk understanding across Australia. The Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning has observed that “[a] lack of widespread flood mapping is evident for some jurisdictions. Without flood mapping it is difficult to impose flood controls.”

The Geneva Association report documented myriad deficiencies in the collection and distribution of flood risk information. For example, some flood mapping databases have a dearth of useful or up-to-date data, while others have restricted access to government use. In addition, “[t]here is no incentive to digitise legacy datasets, which are often restricted by consultants’ licence agreements and cannot be shared publicly”. Although the Insurance Council of Australia has collated local government flood mapping into a national dataset, it has only shared this with insurance companies. In its submission to the 2011 Natural Disaster Insurance Review, FMA suggested that it would make sense for the government and insurance industry to share flood information. FMA states that local councils, who are FMA members, often report “large discrepancies between the broad scale flood information apparently used by the insurance industry (but never seen by FMA members) and the high-quality flood information being increasingly generated by FMA member organisations.”

While some local councils will share flood information, others have asserted that potential legal liability has inhibited them from making flood hazard information public. Insanely, this includes councils fearing being sued if flood information adversely affects property values, as revealed in a 2017 paper from the WA Local Government Association entitled “Disclosing Hazard Information: The Legal Issues”. However, local governments are in a bind—as the Productivity Commission report observed, “legal experts have indicated that failing to release reasonably accurate hazard information could be a source of much greater legal liability for local governments than any liability arising from releasing the information.” The Commission recommended that state governments should legislate to protect local governments from liability for releasing natural hazard information and making changes to local planning schemes, “where such actions have been taken ‘in good faith’ and consistent with state planning policy and legislation”, similar to provisions which exist in New South Wales.

The tension between flood mapping and the impact on property development is a longstanding issue. For example, the Geneva Association report documented that in 1984 the NSW Government “almost released flood maps but decided not to due to fear of election backlash caused by reduced property values”.

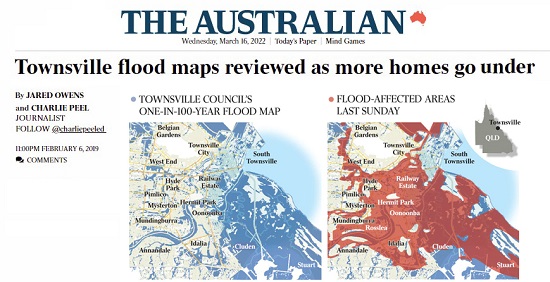

There is no national standard to define flood planning levels in Australia. Most local governments use the 1 per cent Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP) or “1 in 100-year flood” benchmark. The 1 per cent AEP refers to a flood peak level that has a 1 per cent chance of being equalled or exceeded in any one year. (It does not mean that a flood of this severity can only occur once every 100 years, as is often incorrectly assumed).

The Office of the Queensland Chief Scientist has observed that a 1 per cent AEP is usually deemed an “acceptable” risk for development planning purposes, “regardless of the potential consequences of the flood.” Notably, other countries have adopted more stringent flood planning levels; such as the United Kingdom (0.2 per cent AEP or “1 in 500-year flood”); and the Netherlands (0.1 per cent AEP or “1 in 1000-year flood”).

The appetite for “acceptable” risk can differ greatly between the community and developers. For example, a 2015 community survey undertaken by the Townsville City Council found that a 1 per cent AEP benchmark for residential land flooding was viewed as an unacceptable level of risk for the community; however, a 0.2 per cent AEP (“1 in 500- year flood”), was viewed as an acceptable or tolerable risk by most. When devastating floods in Townsville exceeded the 1 per cent AEP event in 2019, Townsville’s five-year-old flood maps had to be redrawn because they did not accurately predict flooding which inundated hundreds of newly developed suburbs and damaged up to 10,000 properties.2

The burden of Australia’s “laughable” flood mitigation policies falls disproportionately on the community and local governments, which are expected to be at the forefront of natural disaster response; meanwhile, local councils are starved of the necessary funding required for them to shoulder this delegated responsibility.

Footnotes

By Melissa Harrison, Australian Alert Service, 16 March 2022