The University of Queensland (UQ) is at the centre of allegations of China’s growing influence over Australia. Politicians and mainstream media outlets have accused UQ of expelling a student for protesting against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). If true, this would be an unacceptable affront to Australia’s commitment to free political expression, but it’s not.

The student in question is 20-year-old Drew Pavlou, who has turned UQ student politics upside down with his personal crusade against China. Drew shot to prominence on 24 July 2019 when he organised a demonstration on the UQ campus in support of the protesters in Hong Kong. The demonstration descended into a physical confrontation between Drew and students from mainland China who turned up to counter-protest. Drew claimed one of the Chinese students brutally assaulted him; however, video footage of the incident revealed that claim to be an over-dramatisation of a scuffle between the two students. Also, fellow students later revealed Drew had spent the days leading up to the protest obnoxiously baiting UQ’s large Chinese student population on social media, seemingly hoping to provoke the reaction he got. When the Chinese Consul in Brisbane issued a statement praising the Chinese students for their patriotism in opposing “separatism”—the independence of Hong Kong from China—Drew claimed it was a death threat against him.

Drew’s antics fitted perfectly with the extreme anti-China coverage that has dominated Western media in recent years, leading to worldwide coverage and instant celebrity status, especially among right-wing Australian and US politicians. He leveraged his celebrity to win a position on the UQ Senate, which he used as a bigger platform to wage his self-aggrandising campaigns against China over Hong Kong, Tibet and especially China’s treatment of the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, which he has repeatedly insisted is “genocide”. It was in his UQ Senate role that Drew ran afoul of the UQ administration, for his repeated breaches of UQ campus policies. For instance, Drew insisted he spoke on behalf of UQ, rather than in a private capacity; and in one incident earlier this year he dressed in a hazmat suit and went to UQ’s Confucius Institute to imply Chinese students carried coronavirus. Eventually UQ expelled him, which allowed Drew and all his right-wing political backers and media to claim was to please the CCP—a claim that has been used to great effect as anti-China propaganda ever since.

Responsibility to Protect

On 12 October 2020, Drew Pavlou shed light on his motivation when he testified to the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee’s inquiry into Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s bill to overrule deals between states and other countries, such as Victoria’s Memorandum of Understanding with China’s Belt and Road project. Drew described how he came to be a leading anti-China agitator in Australia:

“I was never an activist”, he said. “I wasn’t heavily involved in activism before 24 July 2019. I was increasingly reading the news coming out of Hong Kong, reading the news relating to the Uyghur Muslims. I learnt that more than a million Uyghur Muslims were in concentration camps. At the time I was studying a course [on the] history of genocide and as part of that we looked in-depth into the international [inaudible] and also into the international communities’ responses to past genocides, such as the Rwanda genocide. I was reading about these responses and feeling so morally outraged that the world knew what was happening and chose not to do anything; it was just too inconvenient to stop genocide. I thought of the promise that was made in the wake of the Holocaust: ‘never again’; and it was very clear to me that what was happening to the Uyghurs was genocide. There seemed to be a very clear attempt to eliminate Uyghurs as a distinct cultural and ethnic minority group. So I felt that I had no option but to organise a protest.”

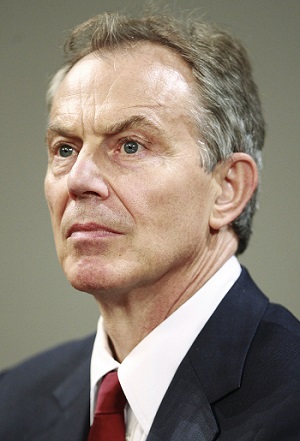

Drew’s testimony was far more revealing then he knows. Twenty-year-old Drew Pavlou believes the greatest human rights atrocity in the world is China’s alleged treatment of Uyghur Muslims. But when Drew was literally a baby, the greatest human rights abuser was supposedly Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Saddam’s alleged atrocities made the claims he threatened the world with weapons of mass destruction more believable, and justified an invasion that ultimately killed a million Iraqis. The principal architect of that invasion, even more so than the White House, was British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who since 1999 had pushed for a new doctrine of international law, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), to replace the principle of national sovereignty that had been the cornerstone of international law since the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia. Blair constantly cited massacres of civilians in Rwanda in 1994 and Srebrenica, Bosnia in 1995 to demand the international community should intervene militarily in nations whose populations were at risk of human rights atrocities by their own governments.

While the USA, UK and Australia’s official reason for invading Iraq was to disarm Saddam Hussein, when the failure to find WMDs proved that pretext had been a lie, the architect of that “sexed up” lie, Tony Blair, quickly moved to justify the invasion under his R2P doctrine—the invasion had removed a “monster”. The same excuse later justified the 2011 US-UK-French intervention in Libya, with its disastrous consequences. Both the Iraq and Libya examples proved that allegations of human rights atrocities had been fabricated and exaggerated to justify an existing regime-change agenda; i.e. “human rights” was merely a pretext for war—the fatal flaw in the R2P doctrine.

Drew Pavlou’s 2019 course on the history of genocide that so effectively shaped his world outlook was taught by Dr Kirril Shields of the Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect based at UQ, a university think tank dedicated to entrenching the Blair doctrine in international law. The bloody recent history of this doctrine shows that the issue is not whether Drew is sincere in his concern for Uyghur Muslims, but whether any of the wild claims he’s been told are even true. Investigations by the Citizens Party and others have shown that, like Saddam’s WMDs, they are not.

By Robert Barwick, Australian Alert Service 28 October 2020

The bloody Blair doctrine

Excerpted from “Treaty of Westphalia vs. Responsibility to Protect”, Almanac, AAS 9 January 2013

From the intervention in Kosovo in 1999, to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Blair steeled the spines of US leaders, insisting that national sovereignty was a thing of the past. He asserted that the era of the nation-state—ushered in with the 1648 Treaties of Westphalia, the series of agreements that ended the Thirty Years’ War (1618- 1648)—was over.

In a 5 March 2004 speech justifying the invasion of Iraq, he laid this out explicitly. He said:

“Let me attempt an explanation of how my own thinking, as a political leader, has evolved during these past few years. Already, before September 11th the world’s view of the justification of military action had been changing. The only clear case in international relations for armed intervention had been self-defence, response to aggression. But the notion of intervening on humanitarian grounds had been gaining currency. I set this out, following the Kosovo war, in a speech in Chicago in 1999, where I called for a doctrine of international community, where in certain clear circumstances, we do intervene, even though we are not directly threatened. .. So, for me, before September 11th, I was already reaching for a different philosophy in international relations from a traditional one that has held sway since the treaty of Westphalia in 1648; namely that a country’s internal affairs are for it and you don’t interfere unless it threatens you, or breaches a treaty, or triggers an obligation of alliance....”

Interestingly, in the 1999 Chicago speech he referred to, he couched the need to overturn “the principle of non-interference” in terms of globalisation. “[G]lobalisation is not just economic. It is also a political and security phenomenon,” he said. Just as “we cannot refuse to participate in global markets if we wish to prosper”, the same holds in regard to security. We are in a new world and need new rules for international cooperation. He thus pushed what he called a “new doctrine of international community.”

Another figure who came out after 9/11 demanding the end of the Westphalian era was National Security Advisor and Secretary of State under Nixon and Ford, Henry Kissinger:

He wrote in the Fall 2002 NPQ magazine that, “The controversy about pre-emption ... At bottom it is a debate between the traditional notion of sovereignty of the nation-state as set forth in the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 and the adaptation required by both modern technology and the nature of the terrorist threat.”

The main funder of US President Obama’s election, the international financier George Soros, is the other key figure who has long been promoting R2P.

In a January 2004 article in Foreign Policy magazine, Soros stated that “Sovereignty is an anachronistic concept originating in bygone times when society consisted of rulers and subjects, not citizens. It became the cornerstone of international relations with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. …

“The rulers of a sovereign state have a responsibility to protect the state’s citizens. When they fail to do so, the responsibility is transferred to the international community.”

The R2P doctrine was formally proposed at the United Nations in 2005 and has been heavily pushed ever since. However, it has never been accepted as international law by the UN. Even after a lengthy debate in July 2009, only a rather weak resolution to continue to consider the doctrine was passed. The non-aligned movement, of 118 members and 18 observer nations, opposed the R2P concept as a danger to national sovereignty and a tool of selective punishment.