By John Lander. The author worked in the China Section of the Department of Foreign Affairs in the lead-up to the recognition of the People’s Republic of China in 1972 and several other occasions in the 1970s and 1980s. He was Deputy Ambassador in Beijing 1974-76 (including a couple of stints as Chargé d’Affaires). He was heavily involved in negotiation of many aspects in the early development of Australia-China relations, especially student/teacher exchange, air traffic agreement and Consular Relations. He has made numerous visits to China in the years 2000-2019.

The increasingly confrontational approach by Australia towards China, especially the talk of going to war over Taiwan in conjunction with the United States, should be of great concern to all Australians, whether they have a favourable opinion of China or not.

Australia needs to chart its own course Cabinet Submissions and other documents in 1970-72, devising a strategy for transferring diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China to the People’s Republic of China, made it clear that Australia would inevitably have to deal with China in a manner untethered from the US approach.

Of particular pertinence is Policy Planning Paper QP11/71 of 21 July 1971 (then Secret/Eclipse, now declassified). It argued that there was “cause for concern whether our alliance with the United States can protect us at every step from political disadvantage resulting from the manner in which the United States conducts its global policies…. The American alliance, in a changing power balance, will mean less to us than it has in the past.”

“If anything, this argument has been strengthened by recent United States actions and America’s failure to consult us on issues of primary importance to Australia. Accordingly, we shall need, now more than ever, to formulate independent policies, based on Australian national interests and those of our near neighbours, that will enable us to react quickly to developments in United States’ policy towards China and Indochina” (and the rest of Southeast Asia).

Our present predicament is due largely to a failure of recent Australian Governments to take this analysis to heart and act upon it. It is as true today as it was in the 1970s.

The souring of a friendship

Australia’s relations with China during the last quarter of the twentieth century were characterised by a spirit of collaboration in many areas of economic and cultural activity where we could find mutually beneficial common ground, while not shying away from open disagreement on matters where we did not see eye to eye.

Until recently the partnership has served both sides well. Good will and attendant economic benefit has been squandered.

China’s trade sanctions against Australia, cited as signs of China’s “belligerence” justifying Australia’s hostility, have been in response to an undeniable shift to a more hostile stance by Australia:

- seven years of anti-dumping measures against Chinese imports;

- blocking of Huawei, instead of a technological solution to security concerns;

- demonisation of Chinese participation in educational and cultural activity—akin to the activities of the British Council, the Alliance Française, the Goethe Institute etc.;

- the consequent demonisation of students from China (and of Chinese Australians);

- the call for investigation into the origins of COVID-19, clearly directed at blaming China;

- interference in Xinjiang on the grounds of fictitious human rights abuses; and most importantly,

- overt support of “democratic independence” movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Taiwan

The status of Taiwan is not central to Australia’s core interests.

When Australia established diplomatic relations with the Nationalist government of China in 1941, it did so on the understanding that Taiwan was a province and integral part of the territory of China. When the Nationalists fled to Taiwan our position did not change, although we did not establish an Embassy in Taipei until 1966, which was removed in 1972, when Australia finally recognised the PRC.

Hong Kong

Likewise, Hong Kong is not a core interest of Australia.

When the lease, acquired by Britain by force of arms, expired in 1997, the PRC resumed authority over Hong Kong. It conceded that Hong Kong could be a SAR (Special Administrative Region), with its own system of internal government, but secession was not an option (as with Taiwan). Meddling by the US Central Intelligence Agency’s National Endowment for Democracy and other external organisations in independence movements in Hong Kong amounts to interference in a country’s internal affairs, in direct breach of the Charter of the United Nations.

Futility of War

War with China over Taiwan or Hong Kong would be futile.

Australia is no match for China’s military strength and we would be foolish to rely on the United States for protection. The United States has already shown, by its actions in Afghanistan, that it is willing to sacrifice the interests of its allies. It did not consult us or its NATO partners on the timing or modalities of abandoning Afghanistan. In response to complaints about lack of coordination with allies, President Biden said the USA would only act “in its own interest”.

Feeding the ‘fat cats’

The recently announced AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine deal, aimed so overtly at China, has greatly undermined Australia’s security. It seems quite patently engineered by the US military-industrial complex, through the American/Australian intelligence community, which has manufactured the “threat from China” out of thin air. It has been unable to show a single instance of Chinese military aggression, citing instead China’s response to the massive buildup of US naval and air power in the South and East China Seas as a sign of Chinese “belligerence”. Freedom of navigation is vital to China’s trade, and the line-up of US naval might along its coast raises fear of a blockade. For China, it is a painful reminder of the “gunboat diplomacy” of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Now that the US military-industrial complex has lost the $300 million per day from the war in Afghanistan, it sees rich pickings in Australia—especially if it succeeds in provoking actual military conflict between Australia and China, in which many Australian assets would be destroyed and would have to be replaced under lucrative contracts to American armaments manufacturers. They have always been unconcerned about loss of life (900,000 in Afghanistan alone).

Bilateral and regional economic suicide

Support for the United States’ objective of decoupling China from the world economy would be equally futile. It would only succeed in decoupling Australia from China.

One hundred and sixty other countries, including all of our Southeast Asian neighbours, have signed up to China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”. The Chinese Foreign Minister’s recent visit to the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries has reaffirmed their shared economic and infrastructure development partnership.

New Zealand has taken the same approach as all our Asia-Pacific neighbours, showing that it is possible to chart a middle course in relation to China. Australia is cutting itself off from constructive involvement in its own region and is now dangerously isolated.

Even the United States itself has remained coupled to China, moving in to take over trade gaps created by Australia’s foolish attempts to “stand up to” China.

Pull back from the brink

The most effective way to avoid military conflict is to be in a friendly relationship.

Australia needs desperately to return to a level of friendship with China, however qualified that must be by the many differences in our political systems.

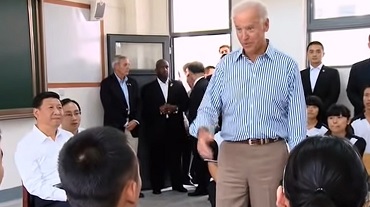

In his visit to China as Vice President in 2011, Biden told then-Vice President Xi “we welcome a rising China. If China is prosperous, if 1.2 billion people continue to grow and modernise and expand, that’s good for the US”. Australia should do everything it can to persuade President Biden to return to that view.

Now that President Biden has once again blindsided Australia by assuring President Xi Jinping (on 9 September) that he would not abandon the “one China policy”, Australia could take a similar step. A public statement could be issued reaffirming the terms of the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations (“Paris Agreement”), 21 December 1972.

The communiqué states:

“…[T]he Australian Government recognises the Government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China, acknowledges the position of the Chinese Government that Taiwan is a Province of the People’s Republic of China and has decided to remove its official representation from Taiwan before January 1973”.

This would concede nothing that has not already been conceded. It could include a reminder of the understanding underpinning Australia’s recognition of the PRC that Beijing would designate the province as an SAR (Special Administrative Region) with the ability to determine its own system of internal government.

The COVID-19 crisis

Another step to improve the atmosphere would be to call on the World Health Organisation (WHO) to extend to Europe and the Americas its investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

Italy (September 2019), France (December 2019) and Brazil found traces of the virus dating from before the first case in China.

In the USA, blood samples showed that the virus was present in 9 States from November 2019 to January 2020. In July 2019 the CDC shut down the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, Maryland because of a failure to meet biosafety standards. Shortly after that, starting in September 2019, there was an outbreak across the US of a mystery disease with COVID-19 symptoms, with 2,600 people hospitalised across 50 States by mid-January 2020. The mystery disease was linked to the practice of vaping (e-cigarettes) because at that stage COVID-19 had not been identified.

The first case in Wuhan was on 27 December 2019 and China reported to the WHO on 31 December 2019. It warned of the virus’ pandemic potential and briefed the Head of the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in person on 3 January 2020. A few days later, thenPresident Trump was briefed on the virulent and lethal nature of the virus. He withheld this information from the public, stating on 21 January 2020 that his “friend Xi (Jinping)” had everything under control in China and there was nothing to worry about.

If we supported a truly independent investigation into all this, it would reassure China of Australia’s impartiality.

Ending the stand-off

These two steps would help to ease tensions and possibly contribute to conditions for the resumption a cordial dialogue with Beijing.

Published by Australian Alert Service, 22 September 2021