When asked about “climate change” and the recent bushfires across Australia, Minister for Natural Disaster and Emergency Management David Littleproud told ABC News that it would be “remiss … to suggest that it is not climate change that has caused a lot of this”. This is the official position of the federal government, which also signed on to the 2015 Paris Agreement to reduce Australia’s emissions by 26-28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. But a historical study of bushfires in Australia and overseas shows that fuel loads and forest management are the overwhelming contributing factors to bushfire threat. Heatwaves, dry conditions and wind clearly increase bushfire risk, as does rainfall in the preceding months, which builds up a fuel load. Meteorological records, however, do not identify dramatic trends in such weather events.

Past bushfires have been much larger. The Black Thursday fires of February 1851 covered a quarter of what is now Victoria and burnt out about five million hectares. The Portland Guardian reported “a period of extraordinary heat” and “a hot wind blowing from the N.N.W. in a most furious manner”. The temperature reached 112 °F (44.4 °C). The Black Friday fires of January 1939 burnt an area of almost two million hectares in Victoria. This occurred during a record heatwave across southeast Australia. Newspapers at the time reported temperatures of up to 121 °F (49.4 °C) in the Mallee, 116.9 °F (47.2 °C) in Adelaide and 113 °F (45 °C) in Melbourne.

The worst bushfires in Australia’s history with respect to loss of life occurred in 2009 with the Black Saturday fires in Victoria, but despite the tragedy, the total area burnt was just under 430,000 hectares. Following the Black Saturday bushfires and the heatwave at the time, William Kininmonth, former head of the Bureau of Meteorology’s National Climate Centre, poured cold water on climate change alarmism: “It is fashionable to promote climate change as being a contributor to changing fire frequency and intensity. The pattern of rainfall over the past century does not point to a trend of reduction in rainfall. Nor has any link been offered between global temperature trends and the meteorology of Victorian heatwaves.”

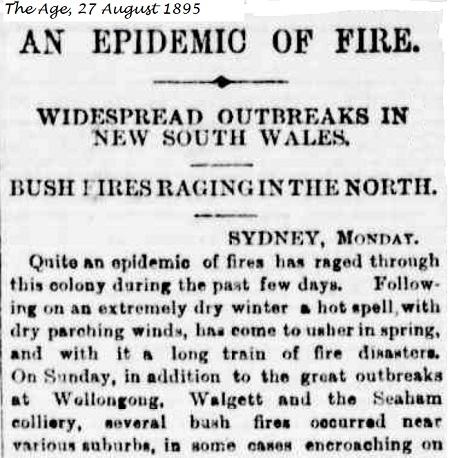

Alarmists suggest that bushfires in September, so soon after winter, are a sign that catastrophic climate change is already upon us. An ABC Background Briefing report this month ran with this line: “The bushfires of the future are already here. They burn earlier in the season, and more ferociously, and can interact with extreme weather events to create fires we don’t know how to fight.” But bushfires early in the season are not unprecedented. The Broadford Courier and Reedy Creek Times of 13 September 1895 reported the dire situation then: “So far, speaking for the colony generally, the rainfall has been considerably below what it was up to this time last year. In fact the winter has been a rather ‘dry’ one, and if no more rain comes, it will be a very serious matter for many farmers and graziers, especially in the more arid portions of the colony. In New South Wales, bush fires have been raging, and complaints are many and frequent from many parts that a drought has already set in. The occurrence of bush fires in August and September is a very ominous sign, and the northern colony is bound to suffer much even if the remainder of the season is favourable.”

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s CEO Andrew Johnson has claimed “there is a very strong climate change signal in the fire risk in this country”. Johnson is also a director of the Planet Ark Environmental Foundation, a radical environmentalist organisation which is currently chaired by Macquarie Group director Michael Coleman . This position on climate change emanating from the banking establishment does not match reality on the ground.

Fuel load is the issue

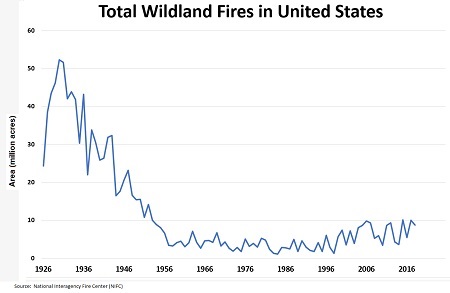

As previously reported in the AAS,1 media coverage of wildfires in Greece, Sweden and California etc., continually point to “climate change” as the overriding problem when in fact the evidence points to fuel load and forest management. Fires in Sweden at the start of the 19th century, for example, burnt out an area more than tenfold that of the 2018 fires and this occurred just about every year. Then Sweden successfully employed good forest management including prescribed burning, and fire severity rapidly declined. Similarly, in the United States forest fires burnt out about tenfold the area in the 1930s than what occurred in the latter half of the 20th century. But restrictive land-clearing laws introduced in recent years have seen fuel loads build up, and fires are now increasing.

Similar restrictive land-clearing laws are now being introduced into Australia. For example, in May 2018 the Queensland Labor government tightened land-clearing restrictions on farmers. AgForce Queensland CEO Michael Guerin told rural news website AustralianFarmers in March that such laws had contributed to Queensland’s 2018 December fires because farmers were prevented from managing fuel loads and from clearing adequate fire breaks. “Taking the management of the land away from those who know and understand it best can have disastrous consequences. Feral pests and weeds spread quickly and the risks of wildfire grows with increased fuel loads. Queensland already has strict laws in place that limit what farmers can and can’t do on their own land, including harsh penalties for non-compliance,” Guerin said. The Australian on 16 July reported that farmers are too scared to clear firebreaks on their land for fear of breaking vegetation clearing laws.

While the banking establishment want us to focus on “climate change”, good forest management and reducing fuel loads must be a priority to mitigate future bushfires.

1. “Wildfires spark climate, forest management and austerity debate”, AAS, 22 Aug. 2018.