If growth slows in the USA it would spark a wave of downgrades of debt instruments and subsequent defaults, which could set into motion a chain reaction of market meltdowns. The core of the bomb is the corporate debt bubble, but its submunitions include overextended financial institutions, the stock market and numerous other debt bubbles. Its detonation can set off the mother of all bombs—the quadrillion dollar-plus global derivatives bubble of financial gambling.

Warnings of a US slowdown are growing, particularly as the impact of the trade war with China hits, with costs for American households and manufacturers rising, and farmers facing a major collapse in sales. According to financial website TheStreet, on 30 May US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin convened a meeting of the Financial Stability Oversight Council, formed to identify financial risks after the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC). The heads of the US Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Commodity Futures Trading Commission all heard about concerns regarding the corporate debt bubble.

The surge in corporate debt rated just above junk-level which could soon be downgraded—more than US$3 trillion by Standard & Poor’s figures—had already been the subject of a warning from the president of the Dallas Fed, Robert Kaplan, according to the TheStreet. The Treasury presented data to the group showing that anywhere from US$300 million to US$1 trillion of this debt could be downgraded if a downturn occurs.

Bank of America has warned that “credit stresses are multiplying”, and if credit is restricted as a result, the stage is set “for elevated distress and eventual defaults”. Even Fed Chair Jerome Powell warned in a 20 May speech that there is a “moderate” risk that stressed debt could trigger a financial crisis if the economy weakens. “Once again”, he observed, “we see a category of debt that is growing faster than the income of the borrowers even as lenders loosen underwriting standards.” The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency reported the same day that “years of growth, incremental easing in underwriting, risk layering and building credit concentrations result in accumulated risk”.

Shadow bank risk

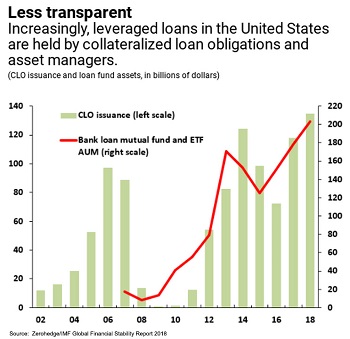

Since the GFC, a major fueller of the corporate debt bubble has been shadow banks (non-bank lenders), including asset managers, hedge funds, private equity firms and even insurers, which fund themselves with junk-rated loans. They package the junk into the corporate equivalent of 2008’s Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs, built upon dodgy mortgages), known as Collateralised Loan Obligations (CLOs). After the crash, banks were forced to keep a minimum level of capital on their balance sheets in case of crisis, but shadow banks are completely unregulated and unsupervised. An effort is under way to subject shadow banks to a modicum of regulation therefore, by designating them as “systemically important” entities. Former treasury secretaries Timothy Geithner and Jacob Lew, and former Fed chairs Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen wrote a joint letter to Mnuchin and Powell on 13 May pushing the proposal. Mnuchin rejected the move; he was supported by the American Investment Council, the body representing private-equity firms, in a letter also dated 13 May.

Some 2,000 US banks were put out of existence by the 2008 crisis, many of them small, regional lenders. With banking services more heavily concentrated in too-big-to-fail mega-banks, small to midsize company lending was neglected, causing shadow lenders to move in. The 31 May Washington Post cited a top credit strategist from Bank of America saying, “It’s a wild west space. The whole thing has exploded in size, and everyone is getting into it.” With none of the restrictions put on banks, non-bank lenders engaged in riskier lending with few or no covenants governing the loans, wrote Washington Post columnist Prof. Steven Pearlstein in a major investigation titled “The shadow banks are back with another big bad credit bubble”. Attracting capital in search of higher returns—including from banks—this new sector has churned up a highly volatile seam within financial markets. Pearlstein reported that “the fastest growing category of revenue and profit for the banks in recent years has been lending to ‘non-bank financial institutions’.” This means depositors’ money is right in the firing line!

Pearlstein wrote that the risk might be justified were the finance going towards productive economic activity or investment in new technologies, but “Companies have used much of this newly borrowed money to buy back their own shares, pay special dividends to private equity investors and acquire other companies, all of which have the effect of inflating stock prices.” Financial authorities are sitting on their hands, said Pearlstein, ignoring the obvious threat in favour of a bit of extra “economic growth, corporate profits and investment returns”, for which we run the risk of “of acting too late and winding up with a financial and economic train wreck”.

Former Wall Street banker Nomi Prins on 23 May warned BBC viewers in the UK of the new, oncoming crisis. In a pre-produced clip Prins laid out the reality that there was no significant reform of the global banking system after the 2008 crisis. If we don’t finally tackle this challenge, she said, we will sink into “an epic credit crisis”, which “will hurt the poorest people even harder than last time”. Rather than fixing the broken system, governments allowed central banks to print money, which further inflated the speculative bubble, Prins explained. She swept away host Andrew Neil’s objections in the ensuing debate that there couldn’t be a bust because there has been no boom—a bust always follows an economic boom, he insisted. Prins explained that this time the “boom” is in the debt bubble, in financial assets, making a new crash so much the worse when it comes.

Jonathan Rochford, Portfolio Manager for Narrow Road Capital, in an article for independent financial publisher Cuffelinks titled “Tech Wreck 2.0 and Debt Wreck 2.0 are coming”, recounted some of today’s eerie similarities with both the 2008 crisis and the 2000 “dot-com” crash, in both debt and share markets. Many tendencies bear the hallmarks of past speculative ventures, with investors “buying securities that have identical characteristics to the disasters of the recent past”. Revealing that we haven’t learn from our mistakes, Rocheford wrote that we “might be witnessing the beginning of a necessary and inevitable process of taking out the investment trash”.

Six signs of GFC déjà vu

1. Housing bubbles are bursting. Australian housing markets are in decline, with prices falling from their peak by over 10 per cent in Sydney, 16 per cent in Perth and 23 per cent in Darwin. With a slight slowing of price falls following government initiatives to prop up the bubble (See “Money pumping is resuming”, below), CoreLogic has optimistically put its forecast for top-to-bottom falls at 19 per cent for Sydney and 15 per cent for Melbourne.

Like Australia’s, Canada’s housing bubble didn’t crash during the GFC. Growth in some cities, driven by high foreign capital flows, is still offsetting national averages, but Toronto house prices are down 4.3 per cent from their July 2017 peak. The IMF’s April 2019 Global Financial Stability Report warned that Canadian cities are vulnerable to a correction, like the USA in 2008.

Even Ireland, which had its property market wiped out post-2008, is poised for a new crisis. A 1 April Bloomberg article, “Ireland property rush risks repeat of crisis”, reported that “home values have been roaring back as if the last crash never happened”, with house prices up nearly 80 per cent since the trough in 2013. A big factor is private equity firms and hedge funds that bought up distressed properties on the cheap. The OECD’s May economic outlook warned that surging property prices combined with slowing economic growth “may lay the foundation for another boom-and-bust cycle”, with the sector especially vulnerable due to the high level of foreign investors (accounting for more than half of commercial property investment).

2. Debt bubbles are ready to burst. In addition to the corporate debt bubble reported above (“Cluster bomb set to go off in US markets”), there are many other bubbles of varying sizes, sometimes referred to as the Everything Bubble, including in stock, bond and equities markets; personal debt; housing; auto loans; student debt; cryptocurrencies; and derivatives.

3. Stock markets are booming but volatile. In mid-April the Dow Jones index was within 1 per cent of its October 2018 all-time high of nearly 27,000; but markets always climb rapidly before a major crash. Banks shares are among the shakiest pre-crash, and today Deutsche Bank is taking the lead. With a 4.5 per cent share price fall on 3 June, the megabank’s shares are down over 90 per cent from their pre-GFC peak.

Signs of an oncoming crisis can be seen in the number of IPOs (initial public offerings or newly floated companies) which are unprofitable, including major players like Uber. “This topped 80 per cent in 2000 at the height of the tech bubble, but this level was surpassed in 2018”, wrote Jonathan Rochford for Cuffelinks on 29 May. Prof. Steven Pearlstein, in the 31 May Washington Post, reported: “The recent wave of richly priced mergers and overpriced stock offerings, and the declining returns offered by recent commercial real estate deals, are all good indications of a credit bubble waiting to burst.”

4. Money pumping is resuming. Money pumping initiatives to keep these bubbles inflated have resumed, indicating nervousness that they will burst without further injections. Less than two years into the reversal of Quantitative Easing (QE) money printing, the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank are pulling up. The Fed will stop unwinding QE this year and may well restart it. It cut short its plan to normalise rates and is expected to resume interest rate cuts at the first sign of trouble. Europe, which ended new QE purchases in December, has already resumed an easing policy, and signalled it would not raise rates in 2019.

Australia is expected to cut interest rates perhaps as low as 0.5 per cent, according to JPMorgan Australia’s analysis. Citi’s chief Australian economist Paul Brennan recently called on the government to make “government cash handouts to households for spending, financed by a permanent increase in RBA [Reserve Bank of Australia] money supply”, an extreme form of quantitative easing known as helicopter money. The RBA considered such approaches in a 2016 study of unorthodox approaches to monetary policy.

5. Regulations are being loosened. In the last three weeks the Australian government has rushed into place a 5 per cent deposit scheme for first home buyers, waiving the requirement for a 20 per cent home deposit; bank regulator APRA plans to scrap the 7 per cent minimum interest rate at which long-term affordability of mortgages is assessed; and the RBA has made the first of perhaps three or four interest rate cuts, to new record lows.

In America, “US mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been busy cutting back on the down payments required and loosening restrictions on the minimum income a borrower needs to service a loan”, wrote Jonathan Rochford for Cuffelinks. This is also happening in Canada, Spain, several countries in Northern Europe, and Australia, he continued.

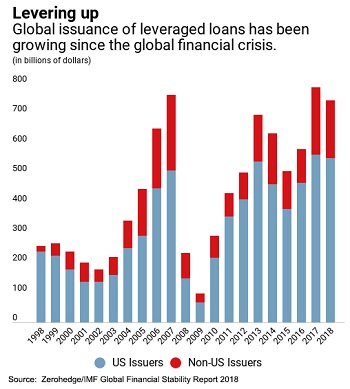

Standards for corporate lending have gone down the toilet, as reported above. “Global high-yield debt markets seem determined to go beyond the stupidity seen in 2006 and 2007.” Pre-GFC, 30 per cent of leveraged loans were covenant-lite, reported Rochford; “Today only the worst of the worst borrowers can’t obtain a covenant-lite loan.”

The Washington Post’s Pearlstein added, “During the first three months of this year, according to Trepp, a data company, interest-only loans—loans requiring no payback of principal until the loan is due—accounted for three-quarters of all new commercial real estate loans.”

6. Sovereign debt crises are back on the cards. Sovereign debt crises will re-emerge because debt continues to grow while the real economy shrinks. The so-called doom loop where bank failures lead to sovereign debt crises and vice versa is still in play, as nothing has intervened to break the cycle. The latest Deutsche Bank crisis could provide a case in point. The same is true of emerging markets, which are deeply saturated in the US dollar debt pumped out heavily since 2008, with currencies that could collapse at any moment and little in the way of dollar reserves.

Australian Alert Service 5 June 2019