With plummeting share prices and fleeing deposits more mid-sized US lenders are set to collapse. Failing with them, however, is the narrative about the causes of the crisis. With every bank collapse, a little more of the gargantuan problem being actively concealed by US banking authorities is coming to light.

Many regional US banks expanded rapidly in recent years by utilising the easy money pumped out by the US Federal Reserve over a decade. Much of their lending went into commercial real estate, fuelling another bubble that is set to burst. But this is not a crisis of their making.

When interest rates started rising these banks no longer had a big enough spread between what they were paying to borrow and what they were charging for loans to keep growing. On 30 April, four economists at the Stanford Graduate School of Business released a report showing that 2,315 out of the 4,800 mid-size banks were sitting on assets worth less than their liabilities, making them potentially insolvent if they experienced large withdrawals (p. 10). And as the Fed continues to raise rates, the most recent being a 0.25 per cent increase on 3 May, the distressed assets and capital value of banks keep depreciating.

In a 14 February report, titled, “Impact of Rising Rates on Certain Banks and Supervisory Approach”, the Fed acknowledged some responsibility for the precarious situation. It noted that due to rising rates, “722 banks have reported unrealised losses exceeding 50 per cent of their capital”. Its conclusion reads: “The rising interest rate environment is increasing financial risks for many banks. We are concerned with banks that have investment portfolios with large unrealised loss positions. As rates rise, investment portfolios which have traditionally been a source of liquidity will be further limited. Higher than anticipated deposit outflows and limited available contingency funding may cause banks to make difficult choices, including reliance on higher-cost wholesale funding or curtailing lending.”

The top contenders among mid-sized banks for bankruptcy include Los Angeles-based Pacific Western (PacWest) Bank with $41 billion in assets (all figures in US dollars); Phoenix-based Western Alliance with $68 billion in assets; and Salt Lake City-based Zions Bank with $89.6 billion in assets. If they were to fail, it would increase the total of assets wiped out in US bank failures since 10 March to nearly three-quarters of a trillion dollars.

To take the first of these banks as an example, PacWest stocks lost 50 per cent in trading in just one day, on 3 May. The next day the bank had lost 20 per cent of the deposits that it had held at the end of 2022, USA Today reported. Shares only rebounded somewhat after PacWest sold a parcel of real estate construction loans on 22 May.

As AAS reported on 10 May, and Wall Street on Parade financial website reinforced 22 May, the deposit wipe-out is not a small bank phenomenon. In fact, the largest 25 US banks, the so-called too-big-to-fail banks, led the deposit purge. Fed data shows that between April and December 2022 deposits at the big banks collapsed by nearly 500 billion. In the same period, a $25 billion deposit gain was made by America’s smaller 4,000-plus banks. But headlines beginning in March of this year, even as large banks continued to haemorrhage deposits, blared: “Large US banks inundated with new depositors as smaller lenders face turmoil” (13 March Financial Times, subheaded, “Failure of Silicon Valley Bank prompts flight to likes of JPMorgan and Citi”). The Washington Post ran a Bloomberg column pushing the same propaganda, on 28 April, reporting, “the big banks have capitalised on massive depositor inflows, clearly related to the well-documented liquidity stresses facing their smaller, regionally based brethren. This should come as no surprise. The panic-fueled depositor exodus from the smaller banks to the larger ‘too big to fail’ banks is simply a rational decision.”

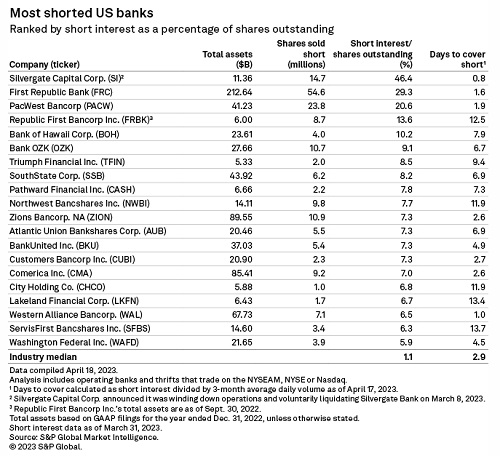

But it’s worse than just a subverted media narrative. The big players have deliberately shifted the crisis onto the smaller ones, by shorting their shares, thereby forcing deposit losses and bankruptcy, then swooping in to take them over. Witness the list of the most shorted US banks prepared by SP Global (right). Currently at the top of the list are just-collapsed banks (Silvergate, First Republic) and those forecast to be next (PacWest). Other targets featuring on the list are Western Alliance, Comerica and Zions Bank.

Big banks are short selling the smaller ones—offering them up as the sacrifice in order to replenish their own liquidity and concentrate their own control. It is time that such speculation be outlawed, or at least domiciled away from retail customers. (Short selling explained—p. 12.)

The media narrative then feeds back in, completing the cycle. For instance, a 21 May Wall Street Journal article reported that the banking crisis has “only made JPMorgan stronger”. The deal the bank did with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), to take over First Republic, was so sweet, the real question, raised by WSOP, is: “who got the bailout: uninsured depositors at First Republic Bank or JPMorgan Chase?”

What to do about deposits and insurance?

Bank deposits continue to decrease each week, with no solution offered by banking regulators. Deposits fell by over $26 billion in the week ended 10 May, according to Fed figures, bringing the total exodus since April 2022 to over $1 trillion. The fall in deposits is accompanied by a decline in commercial and industrial lending, which has dropped $45 billion since January. The Fed is forecasting a further “sharp contraction in the availability of credit ... potentially resulting in a slowdown in economic activity”, in its biannual survey of risks facing the US economy.

Despite rising interest rates, in February JPM Chase and Bank of America were still paying only 0.01 per cent on deposits. The six-month US Treasury Bill yield at that time was 4.87 per cent, tempting depositors away. Wall Street On Parade reported 17 May on a dramatic rise in TreasuryDirect accounts at treasurydirect.gov, a site where investors can buy directly from the US Treasury. The number of accounts has grown 543 per cent, and the value of US Savings Bonds and Treasury Bills purchases are up 804 per cent, in the year from 2021-22.

Given the pledge to guarantee even uninsured deposits in SVB and Signature Bank in March, a debate about deposit insurance has also broken out. There have been a range of proposals, including insuring all deposits across the board. With estimates of uninsured deposits ranging from $7-9 trillion, it is generally recognised that this would be impossible. The Deposit Insurance Fund held $128.2 billion at the close of 2022 and it has since taken a thrashing. Some have warned against insuring all deposits, for fear of encouraging bad bank activity. Others have suggested putting a cap on the level of uninsured deposits a bank can hold. (Nearly 94 per cent of SVB’s deposits were above the level insured.)

To recover the losses incurred by protecting uninsured depositors at SVB and Signature Bank, around $15.8 billion, FDIC chair Martin Gruenwald proposed a special assessment on 10 May, to be levied on 113 large and middle-sized banking organisations over two years. It also put forward options for deposit insurance reform, including raising the $250,000 insurance limit, unlimited deposit insurance, and more targeted coverage including greater limits on business payment accounts, with a preference towards the third option.

Members of Congress, including Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren, have proposed raising the $250,000 limit of deposit insurance to a higher level for all depositors. Some banking organisations are promoting this solution.

In a 9 May op-ed for the London Financial Times, head of the FDIC from 2006 to 2011 Sheila Bair wrote that “universal coverage” of all deposits by the FDIC is not a good idea, but some expansion is needed, likely for “transaction accounts” run by business. In the 2008 crisis the FDIC could make targeted emergency increases to deposit insurance, she said, but now it must be authorised by Congress. Bair noted that much of the current hysteria is being drummed up by “media hype and short selling pressure”, which is making depositors nervous. She canned universal coverage of deposits, saying that “reckless banks could offer high yields to attract large depositors who would ignore the risks, knowing the FDIC would protect them.”

In the 17 May FT, banking and regulation expert Todd Baker, of Columbia University, made a critical point. Deposit insurance worked originally, he wrote, because it dovetailed with a strict regulatory architecture. “At the same time, the US developed a comprehensive system of bank regulation to complement deposit insurance, including strict separation of banking from securities and other commercial activities.”

Bank runs stopped for almost 90 years, most banks were consistently profitable, failures were rare and, as the FDIC proudly states, “no insured depositor has lost a penny”.

Baker reviewed different proposals such as expanding insurance to cover all deposits, creating special money-market funds with loss-absorbing capacity, or privatising the insurance system. “As for returning to the low-risk world of Glass-Steagall?”—the referenced banking separation—he says, “Even a supermajority in Congress couldn’t unbake that cake.”

He nonetheless pushes in that direction, quoting FT’s chief economics commentator Martin Wolf, who insists: “the essential point is that banks are, really are, utilities. ... And if they are to be seen as utilities, they don’t need to be vastly profitable. They need to be run as utilities and be capitalised in ways that ensure that they will survive in tough times. Because surviving in tough times is the most important thing banks can do.”

Baker’s conclusion: “State and federal law should be changed to explicitly require bank boards to consider the interests of the FDIC insurance fund and the larger economy in the exercise of their fiduciary duty as corporate directors. And the FDIC should be able to sue them if they don’t.

“These solutions aren’t very complex, nor do they require new deposit insurance structures based on economic theories that have regularly failed to conform to our human-centred reality in practice. Will they work? It’s certainly worth a try?”

A bill to reinstate Glass-Steagall, introduced in April by Ohio Democrat, Rep. Marcy Kaptur, The Return to Prudent Banking Act of 2023, H.R. 2714, is gaining publicity and traction, with 11 listed co-sponsors. Glass-Steagall is the only sure way to effectively protect all deposits by housing them in financial utilities barred from engaging in risky activities.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 24 May 2023