The authorities hope that people won’t notice they have used the cover of the COVID-19 pandemic to bail out the banking system. Of the more than $300 billion the Australian government and Reserve Bank have earmarked for the coronavirus shutdown, $105 billion is a direct bailout for the banks, and a percentage of the rest is an indirect bailout. Suddenly media reports have popped up proclaiming the safety of the banks. So how safe are they really?

Australians are told to believe that the banks are “unquestionably strong”. Note the word, “unquestionably”. This comes straight from the bank regulator, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). Its job is to ensure the financial system is stable, and ostensibly to protect the interests of depositors (although depositors are a lower priority than stability). But what APRA is actually saying to depositors who worry about the safety of the banks is “don’t question it”. From the arguments used in recent media reports to assert the banks are safe, the conclusion must be the opposite—they aren’t.

On 26 March, former top CBA executive Paul Rickard penned an article for switzer.com.au headlined “Aussie banks are as safe as houses”. Given that Aussie houses are no longer safe as houses, but over-inflated debt traps, the headline alone was a big enough clue that the author was spinning a yarn.

Rickard wrote: “In this Coronavirus-inspired market mayhem, one of the sillier rumours doing the rounds is that some ‘Aussie banks could be in a bit of trouble’. It is amplified by ‘conspiracy theory’ nuts who point to an obscure change in 2018 to the legislation governing the banks relating to ‘bailin’ provisions.”

Not surprisingly, the “conspiracy nuts” were the Citizens Party, and Citizens Party legal expert Robert Butler, who authored the legal opinion that the 2018 APRA crisis resolution powers law could be used to bail in deposits. Butler’s legal opinion has been cited by economist John Adams and banking expert Martin North on their Interests Of The People YouTube show, which is likely how it came to Rickard’s attention, as John Adams famously debated his “economic Armageddon” thesis on Rickard’s partner Peter Switzer’s show.

According to Rickard, the bail-in provisions in the 2018 law only concern the conversion or write-off of hybrid securities, a.k.a. bail-in bonds. Robert Butler’s legal opinion, Rickard quoted, “says that bank deposits could be ‘other instruments’, and then cites changes by the banks to account terms and conditions to confirm that they may have the power to ‘bail-in’ depositors. He [Butler] concludes: ‘whilst not beyond doubt … in my opinion … the Act provides for a power of ‘bail-in’ of bank deposits which did not exists prior to the passing of the Act’.

“But Mr Butler totally ignores the lessons of history”, Rickard countered. “No bank in Australia has failed in Australia since the great depression. Depositors’ monies haven’t been touched.” (Emphasis added.)

Besides making the mistake of assuming it can’t happen because it hasn’t happened before, Mr Rickard is himself ignoring something of great relevance to this issue: that as a member of the G20, the Australian government signed off on the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) policy to resolve future banking crises, called “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes”, Section 3.5 of which, called “Bail-in Within Resolution”, includes bail-in of deposits. Put simply, it is irrelevant that deposits have not been bailed in in the past, because the government has signed off on the global postGFC policy that says that is the way banks will be saved in the future. Moreover, the Senate inquiry report on the 2018 bail-in law admitted, explicitly, that it “draws on the criteria” in the FSB’s Key Attributes bail-in policy.

In stating that “Australian banks are among the safest in the world, if not the safest”, Rickard pointed to their:

- high capital ratios;

- high level of domestic deposits;

- emergency funding facility from the RBA called the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF); and

- the $250,000 Financial Claims Scheme (FCS) deposit guarantee.

These were much the same arguments made by University of New South Wales economist Richard Holden in a 1 April ABC article, “Is your money safe in Australian banks during the coronavirus pandemic?” Holden urged Australians not to withdraw their savings, promising the FCS guarantee will protect them. APRA’s stress tests prove the banks are safe, he assured.

Brian Johnson from US investment bank Jefferies was also reassuring: “banks go bust because they run out of cash”, he said. “And the Australian banks have got a lot of cash, a lot more capital than they used to have.” Economist Gerard Minack also weighed in, saying that “ultimately the authorities and the RBA will backstop them so we will have banks, they’re not going to go out of business.”

None of these experts, nor the banks, are admitting that a lot of people have been desperately pulling their money out of the banks for many months now, and the banks are taking increasingly desperate measures to slow or stop it. One sign of the scale of this exit from the banks is that bullion dealers who sell gold and precious metals are out of physical stock. So there is an unstated reason for this sudden expression of confidence in the banks.

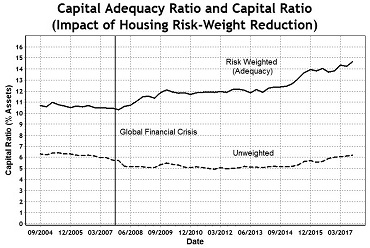

Their arguments are not right, however. Former APRA Principal Researcher Dr Wilson Sy was the first to point out that the $250,000 FCS guarantee is not activated, and therefore it isn’t a guarantee until it is. Dr Sy also knows firsthand the quality of APRA’s so-called stress tests, which he has compared to “snake oil”. And as for the banks having “unquestionably strong” levels of capital, Dr Sy showed that the supposed growth in bank capital after the GFC was entirely due to the ruse of “risk-weighting” mortgages as less risky, and therefore requiring less capital, than other loans. Actual capital has barely budged since the 2008 meltdown.

By Robert Barwick, Australian Alert Service , 8 April 2020