Following a flurry of protest from media outlets, the Indian government on 27 July was forced to issue a denial that it is preparing to reintroduce the controversial Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill 2017 (FRDI), India’s bail-in bill which it withdrew in 2018. In reality, however, it appears to be ploughing ahead in all but name.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced on 7 February that the government had “started to work on [the FRDI bill] again. I don’t know when I will introduce it.” While the Finance Minister was mooting a revival of the bill, behind the scenes work was under way to turn a new proposed “resolution authority” bill into a bail-in Plan B, to usher it in undercover. Reports indicate that key components of the FRDI have sneakily been added into the Financial Sector Development and Regulation (Resolution) Bill 2019 (FSDR) proposed late last year to establish a Resolution Authority. As Indian Express reported on 17 July, the new bill “was seen by many analysts as a bid to bring in a bail-in clause similar to the one in the earlier Financial Resolution & Deposit Insurance Bill”. The bill is expected to be put up at the end of the year.

At the very end of 2019 various media outlets began reporting on the bill with headlines like “FRDI Bill to Come Back as FSDR”. The new bill will amend several existing laws and statutes and unify various regulatory agencies, allowing greater powers to implement a resolution. In the language of the Bank for International Settlement’s Financial Stability Board this means “resolving” capital shortages of banks using various tools including writing off or converting (into shares) certain bonds and deposits, in order to keep the bank afloat. India’s resulting Resolution Authority will be remarkably similar to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) after its powers were enlarged by the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018, which was snuck through Australia’s parliament in a similarly underhanded way.

A review of the bill by MoneyLife calls it the latest version of the FRDI, noting the FRDI included “the controversial ‘bailin provision’ which held out the threat of forcibly converting term deposits with banks (above a certain insured threshold) into equity to recapitalise failed banks”. The bill will correct the fact that “India and a few other countries have yet to put in place ‘an effective resolution regime’”, wrote author Sucheta Dalal. Its Tools of Resolution will include “‘critical powers’ for resolving banks”, including: “cancellation/modification of liabilities” (which category includes deposits); the “power to terminate contracts, write down debt”, take over the bank’s board; and being “empowered to make executive decisions on behalf of the entity”.

New Indian Express insisted that the new bill does not have a bail-in clause, but “the authority can modify liabilities which means they can set a limit to the liabilities that would be paid out”, meaning a percentage of liabilities can be cancelled—precisely what a bail-in is.

It was the infamous “bail-in clause” that led to the demise of the first bill, which was introduced in August 2017 then withdrawn by the government in August 2018 after a political firestorm was unleashed by banks, unions and the general public. An excerpt of author Vivek Kaul’s new book, Bad Money: Inside the NPA Mess and How It Threatens the Indian Banking System, was published in the Scroll on 16 July, from the chapter titled, “What the government wanted to do with our money but didn’t”, to which the paper added, “(but may still want to)”. Kaul explains that whereas a bailout involves “money brought in from the outside to rescue a bank”, bailin is where “the rescue is carried out internally by restructuring the liabilities of the bank”. The fate of the bill was due to “Clause 52”, he wrote, which “allowed the Resolution Corporation to cancel the repayment of various kinds of deposits”, or at the very least impose a “haircut” where “the borrower negotiates a fresh deal and does not repay the entire amount it owes to the lender”. The government informed the parliamentary committee which was inquiring into the bill that it had “decided to drop it due to apprehensions that had developed among people around the ‘bail-in’ clause”, he said.

The Government’s latest statement of “clarification” regarding the bill’s revival said: “There are some media reports about the reintroduction of the FRDI Bill. This is to clarify that the Government has not taken any decision to reintroduce the FRDI Bill.” No mention of the new FSDR bill, though, which was referred to just days earlier by the governor of the Reserve Bank of India who “called for a legislative backing for a resolution corporation to deal with financial sector stress”, according to the Times of India on 27 July. “He said that such an agency will ensure that a financial firm does not end up being liquidated as depositors are more likely to get a better value in the resolution of a bank as a going concern than in liquidation.” This is precisely the language used to justify bail-in—if the bank goes bust you’ll lose everything, but we’ll keep it afloat by stealing some of your deposits or investments. Never mentioning there is an alternative—reorganising the banking system to remove the systemic risk, beginning by banning deposit-taking banks from speculating in risky financial derivatives.

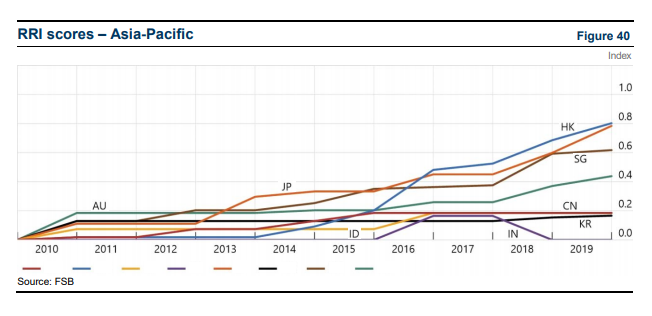

India’s latest move is due to FSB pressure in the face of the new global financial crisis. In October 2019, this author penned an article titled, “Will Indian financial crisis revive bail-in bill?” The question was raised by a growing banking crisis in the country, sparked by collapsing housing and debt bubbles. In September accounts at Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative Bank (PMC) were frozen, the latest in a string of 11 banks the Reserve Bank of India had to intervene in over the previous year. In March 2020, Yes Bank depositors were frozen out of their accounts and there was a bailin of Tier 1 bonds which include a bail-in clause in their contracts, although many investors were unaware (“Indian retirees whacked by contractual bail-in”, AAS 11 March). India is a country the FSB routinely singles out for not having implemented a full statutory (legislative), as opposed to contractual (as in the case of bonds with bail-in in their contracts), resolution regime (“FSB bail-in review: Mind the gap”, AAS 15 July).