Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers grabbed headlines with his announcement on 25 October, as part of his debut Budget, of a so-called National Housing Accord which would “align for the first time the efforts of all levels of government, institutional investors and the construction sector” to build one million new “affordable” and “well-located” homes, including social housing, in the five years beginning 2024. Sadly, though predictably, the wording of the Accord and subsequent remarks by representatives of both the government and the superannuation sector—the largest of the aforementioned “institutional investors”—make clear Labor’s ongoing inability to think outside the strictures of the neoliberal dogma that caused the present economic crisis. Behind its flowery talk of public benefit and national unity, the Albanese Labor government proposes only more of the same market-based model, centred mainly on “incentivising” private financiers by guaranteeing them returns on investment at going market rates, a rehashing of the “Public-Private Partnership” infrastructure-financing model has seen vast sums of public money transferred to private vested interests for no gain during the past four decades.

Meanwhile, every successful past and present social housing and housing affordability program the world over has always been predicated upon direct investment and management by government. And history shows that in light of Australia’s particular constitutional division of responsibilities between the States and the Commonwealth, the best way for a federal government to contribute is via long-term, low-interest credit from a public bank, as exemplified by Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley’s use of the Commonwealth Bank for that purpose under the first Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement (CSHA) beginning in 1945—and, at the State level, by the pro-development conservative government of South Australia, which built not just housing projects for the poor but entire new cities to industrialise the state while improving standards of living for everyone. It is this “bipartisan consensus” that the Albanese government must restore, rather than maintaining the post-1983 neoliberal one, if it is at all serious about achieving its stated aim.

Super: the new ‘Money Power’

The first thing to be said of the Accord is that Chalmers’ figure of one million homes seems little more than a publicity stunt, since the Accord contains nothing approaching an actual plan to build them; it is instead referred to as an “ambition”, an “initial, aspirational target”. What the government has actually committed to, as spelled out in Chalmers’ and Housing Minister Julie Collins’ joint press release announcing the Accord, is $350 million in federal funding “to deliver 10,000 affordable homes over five years from 2024, on top of our existing election commitments.” Per Chalmers’ Budget speech, these election commitments comprise 35,500 homes built in five years by two new federal agencies, the Housing Australia Future Fund and the National Housing Infrastructure Facility. State and territory governments are reported to have “agreed to build … up to 10,000 new homes as well”. Presuming all of the states’ “up to” 10,000 homes get built, that would bring the grand total to 55,000—better than nothing, to be sure, but still 945,000 shy of what Chalmers purportedly aspires to.

But that is where the good news ends. According to Chalmers and Collins’ press release, the promised $350 million in federal funding will not be used actually to build anything, but rather “will incentivise superannuation funds and other institutional investors to make investments in social and affordable housing by covering the gap between market rents and subsidised rents” (emphasis added). The Accord itself elaborates: “Relative to comparable countries, Australia has a low level of institutional investment in housing. At the same time, we have the world’s third largest pool of capital in our superannuation system, which is hungry for investments that will deliver stable returns over the long term for the benefit of members.” Which sounds good in theory—until you learn what big super considers a reasonable return on investment. Speaking 8 November at the Australian Financial Review’s Super and Wealth Summit, Paul Schroder, CEO of $230 billion behemoth AustralianSuper (the nation’s largest superannuation fund), “[said] it must earn returns of between 6 per cent and 11 per cent to invest in residential housing” depending on project-specific development risks, the paper reported that evening, “and won’t accept less under the federal government’s plan to enlist institutional investors to boost housing supply.” Said Schroder: “Do we do some things in affordable housing? Yes, we do. Does it normally stack up? No, it doesn’t. Usually, the risks are too high, and the returns are too low. So that’s been the history of affordable housing. That’s why most people don’t do much of it. … And somebody’s got to make up the difference or reduce the risk or reduce the costs.” Somebody, in this case, meaning the government. In which case, the obvious question is: at a minimum, why would the government not just borrow at its bond rate and build the housing itself? According to the Australian Treasury’s Office of Financial Management (AOFM), the annual interest rate on the longest-dated bonds currently outstanding, which were issued in July 2020 and mature in June 2051, is a mere 1.75 per cent. Presumably wholesale borrowing costs would now be higher due to cash rate hikes by the world’s major central banks in recent months, but surely this would still be the cheaper option by far.

The public solution

There is, however, no real reason the federal government need borrow from private lenders at all. As the Australian Alert Service has reported,1 and as Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Deputy Governor Michele Bullock again acknowledged to Queensland Senator Gerard Rennick during last week’s Senate Estimates hearings (p. 3), powers granted by the Banking Act 1945 and carried over in the Reserve Bank Act 1959 allow the government not only to regulate private banks’ lending policies via the RBA, but to borrow from the RBA on its own account or simply direct the RBA to “print” money for whatever purpose the government sees fit. Nor does Chalmers need to reinvent the wheel where his “social and affordable housing” is concerned, since, as noted above, he has Chifley’s 1945 CSHA as an example of how a federal funding mechanism could work; while the states, for their part, could hardly do better than to emulate the remarkable South Australian Housing Trust (SAHT), one of the most successful public housing agencies the world has ever seen.

Alex North, a United Workers Union organiser and past president of the Australian Unemployed Workers’ Union, provides a useful history of the SAHT in a 20 April 2021 article for the online magazine Jacobin. “The government of South Australia (SA) established the SAHT in 1936”, North wrote. “Over the course of its life, it built 122,000 high-quality homes for hundreds of thousands of workers.” But whereas today only socialists seem to advocate high-quality and affordable public housing, “the SAHT was not the work of a reforming Labor premier” but was established in 1936 by the conservative Liberal and Country League (LCL), and was used to its greatest effect by Sir Thomas Playford IV, whom North describes as “an emphatically bourgeois, anti-union politician who served as premier from 1938 to 1965.”

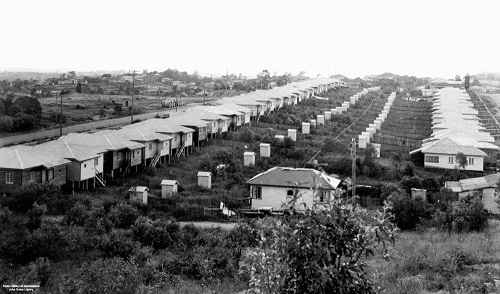

Today, social and public housing is seen by governments across Australia as solely a welfare issue, and at best is maintained at the bare minimum level needed for society’s most downtrodden—and usually not even that. The SAHT, however, was established not as a welfare agency, but a statutory authority. “This meant that it operated essentially as a stateowned company and the de facto planning and development authority for SA”, wrote North, which expanded its remit to “providing housing suitable to the majority of the population … on a scale that is almost inconceivable for a public housing authority today. In 1954, for example, the trust built 47 percent of new residential dwellings. Between 1945 and 1970, it constructed a third of all South Australian homes. … It also built roads, factories, transport infrastructure, leisure amenities, green spaces, schools, football ovals, shops, and cultural venues. It planned and built Adelaide’s satellite cities of Elizabeth and Noarlunga, and even produced films to convince migrants to move there.” (Emphasis added.)

Moreover, it did so on the cheap—for the tenants and the government. At its peak the SAHT was the state’s biggest property developer and biggest landlord, but it never charged “market” rates of rent; rather, it charged what it called “economic rents” at a fixed proportion (usually between one fifth and one sixth) of a worker’s weekly income. “This revenue covered production and upkeep costs while the SAHT turned a profit on sales of their non-rental stock”, North reported. SA did not in fact initially join Chifley’s CSHA, due to disagreements over its home sales policy; but once it did, and federal funding became available, “the trust was able to expand by building and leasing more facilities to the private sector. Thanks to this and the trust’s business model, as SAHT board member and historian Hugh Stretton noted, the SAHT’s first four decades ‘cost the taxpayers nothing’.” (Emphasis added.)

Regarding the genesis of the CSHA, Australian National University academic and former Whitlam Labor government Deputy Head of the Department of Urban and Regional Development Prof. Patrick Troy reported in a 2011 paper that Commonwealth Government engagement in housing had been “very limited until the war of 1939-45 when the conditions were ripe for its leadership. Reviewing the nation’s social security system, Parliament concluded that housing was important in achieving a fairer society.” For example, in the letter of transmittal accompanying an August 1944 report to Parliament, the Commonwealth Housing Commission declared: “We consider that a dwelling of good standard and equipment is not only the need but the right of every citizen—whether the dwelling is to be rented or purchased, no tenant or purchaser should be exploited for excessive profit.” (Emphasis in original.) Accordingly, wrote Troy, “The 1945 CSHA provided loan funds [to State housing authorities, financed by the Commonwealth Bank] over 53 years on the condition that housing was directed, in the first instance, to meeting the accommodation needs of low income families, in particular for the provision of rental housing.”

Due to the vagaries of the constitutional system mentioned earlier, however, the Commonwealth was unable to impose the CHC’s lofty mission statement upon the states; and once Robert Menzies’ Liberals took government in 1949, they immediately began unwinding and eventually destroyed all Chifley’s development schemes (barring Snowy Hydro, which was too far advanced and too popular to kill). Nonetheless, in the CSHA’s first year of operation it enabled the State housing authorities to complete 4,028 houses, or 26.1 per cent of the national total (not including the large number being built in SA, which had not yet joined the Agreement). And spurred on by the CSHA’s operations, and other economic development programs launched during and after the war, “The total number of dwellings completed annually increased nationally from 15,422 to 56,987 by 1949-50”, albeit the proportion that were public housing fell to 13.1 per cent (though again, this does not include SA). The Commonwealth, wrote Troy, had “underestimated the difficulties of creating the capacity in the various State agencies to deliver the program and of getting the States to share its political and program ambitions.” The magnitude of the present economic crisis should at least make that easier this time around; but Chalmers’ ambitions as currently stated will serve only vested interests, not the common good.

Footnote:

1. “A breakthrough in the battle over bank policy”, AAS, 13 Apr. 2022.

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 16 November 2022