More than 18 months after it commenced in September 2020, the public inquiry into the May 2017 suicide bombing of Manchester Arena heard its final testimony on 15 March this year, and is not expected to hand down its final report until late this year. Whatever conclusions may be drawn and currently classified evidence disclosed therein, the inquiry has already put paid to any notion that the perpetrator, Salman Abedi, could possibly have been a so-called lone wolf who had somehow “slipped through the net” as the UK government continues officially to pretend. The testimony of the bomber’s relatives and associates, government officials, and representatives of law enforcement and intelligence agencies make it clearer than ever that so far as the British state is concerned, the lives and wellbeing of its people come a distant second (at best) to the fostering of extremist groups it can deploy as proxy forces in pursuit of its geopolitical aims.

On 22 May 2017 Salman Abedi, a 22-year-old British national of Libyan descent, detonated a home-made bomb at Manchester Arena during a concert by American pop singer Ariana Grande. Twenty-three people including Abedi himself were killed, and another 64 wounded. When Abedi was identified as the bomber, the UK government and the Security Service (MI5) acknowledged that he had long been “known to the intelligence services”, but claimed he was only a “former subject of interest” who was no longer under surveillance. It soon emerged, however, that he had raised far too many red flags for this to be true. The Daily Mail, for example, reported the day after the bombing that “At least 16 convicted or dead [British] terrorists are known to have come from a small area of Manchester and several surveillance operations on suspects from the region have been on-going.” Any such surveillance operation would surely have included the Abedi family which, as the Financial Times reported 25 May 2017, was connected to “networks of radicals that reach back to Libya but also Afghanistan—and is known in turn to have links to al-Qaeda.” Salman’s father Ramadan Abedi, it turned out, was a long-time member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), described in the 30 July 2018 Daily Mail as “a militant organisation founded to pursue the violent overthrow of Qaddafi’s dictatorship and establish an Islamist state. Many of its followers had waged jihad in Afghanistan against the Soviets, and in the late 1980s and early 1990s their aims overlapped significantly with British foreign policy.”

History of extremism

As the Australian Alert Service noted at the time,1 “overlapped” was a major understatement: Britain, the USA and Saudi Arabia had in fact created the so-called Afghan Mujahideen in the late 1970s—from which sprang al-Qaeda and most other Islamist-jihadist terror groups that exist today. Former MI5 officer Annie Machon reported in her 2005 book Spies, Lies and Whistleblowers that Britain’s foreign intelligence service MI6 had by 1995 paid the LIFG hundreds of thousands of dollars to assassinate Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, which they attempted the next year. Ramadan Abedi and his wife had fled Libya for the UK after he was arrested in 1991, accused of exploiting his position as an officer of Libya’s Internal Security Service to tip off the LIFG and other Islamist groups about pending police raids.

Salman Abedi himself had had been repeatedly referred to Prevent, the UK’s deliberately counterproductive “community-based deradicalisation program”,2 over a period of more than five years. According to the 26 May 2017 London Telegraph, one community leader had reported Abedi in 2015 “because he thought he was involved in extremism and terrorism”, while two of his friends separately telephoned the police counter-terrorism hotline in 2012 and again in 2016 because they “were worried that ‘he was supporting terrorism’ and had expressed the view that ‘being a suicide bomber was ok’”. Abedi had also been banned from south Manchester’s Didsbury Mosque “after he had confronted the Imam who was delivering an anti-extremist sermon”, for which he was reported to Prevent yet again. The 28 May 2017 Mail on Sunday reported that earlier that year the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) also alerted MI5 that it had placed Abedi on its own watchlist. When the Tony Blair government restored diplomatic relations with Libya in 1999, the LIFG was designated a terrorist organisation and most members of its Manchester cell placed under MI5 “control orders” verging on house arrest. But when Britain betrayed Qaddafi and launched its 2011 regime-change campaign against him under the cover of the so-called Arab Spring, the control orders were rescinded and their passports returned, and the LIFG became Britain’s “boots on the ground” once again. And as the above-cited July 2018 Daily Mail article reported, “While his Manchester classmates were embarking on A-levels, [Salman] Abedi was taking up arms on a ‘gap year’ at the front line. The teenager had been taken to Libya by his father Ramadan Abedi to fight in the revolution.”

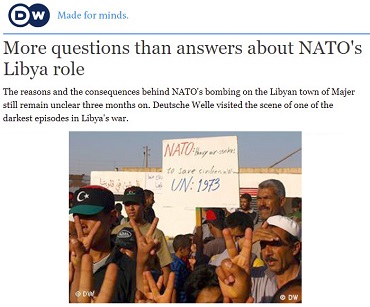

The British, French and US governments have always maintained that the so-called revolution took place organically, after which they supported it only incidentally as a mere extension of their “mandate” from the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to protect Libya’s civilian population from the (fictitious) depredations of the “regime”, and were as horrified as anyone else when mediaeval bloodthirsty Islamist gangs took over. Drawing upon evidence presented to the Manchester Bombing inquiry supplemented by their own investigative work, however, British journalists Mark Curtis and Phil Miller show in a series of three articles published 27-29 June at Declassified UK that the British government and its North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) allies knew exactly what they were doing—and that Salman Abedi, his father, and his elder brother were in the thick of it.

Family affair

According to the testimony to the inquiry of an MI5 officer codenamed Witness J, Declassified UK reported, “MI5 first received information about Salman Abedi in December 2010, linked to another ‘subject of interest’. They said this was a ‘faint link’ and he was not judged to be a threat to national security.” In March-July 2014, he “was placed under active investigation by MI5 but then closed as a subject of interest. But at no point between 2010 and 2017 was Salman Abedi subject to a port stop under the Terrorism Act … [which] gives officers the power to stop, question, search and detain, individuals at UK ports to determine whether they have been concerned in the commission or preparation of an act of terrorism.” (The law applies equally to UK citizens, or at least it is supposed to, for acts of terrorism committed abroad as at home.) This is despite MI5’s acknowledgement that “after 2011 it received information on Salman Abedi’s travel to Libya ‘on a number of occasions’”—on at least some of which he apparently trained alongside members of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Moreover, Declassified UK reported, “the security services knew by 2010 that extremists in Manchester could pose a threat. It was in December of that year that the MI5-led Joint Terrorism and Analysis Centre (JTAC) produced a report on Manchester concluding there was an issue of Islamist extremism among elements in the community” associated with the LIFG. Ramadan Abedi was subject to at least two port stops in 2011, at one of which Salman was present, but was allowed to go about his business after telling officers he “told port officers in November 2011 he’d been on four trips to Libya that year, ‘taking aid and supplies to the rebels’, forces which had the overall support of the UK and NATO.” On at least one of these occasions he also took along Salman’s younger brother, Hashem, who in 2018 was convicted and jailed as Salman’s accomplice in the Manchester Arena bombing. UK government and Libyan sources told the Daily Mail in July 2018 that the two brothers had also been among 110 British citizens rescued in 2014 by a Royal Navy vessel from Tripoli, Libya’s capital city and principal seaport, after the country once again descended into civil war.3

Salman’s elder brother Ismail Abedi “was also left alone by the security services following an even more revealing port stop”, Declassified UK reported. “This occurred on 3 September 2015, as he and his wife were stopped at London Heathrow Terminal 4 after they had disembarked from a flight from Amsterdam. They were interviewed and their electronic items were seized and downloads from them obtained. The Greater Manchester Police (GMP) told the inquiry there was pro-Islamic State material on the downloads including numerous jihadi chants encouraging the killing of infidels and suicide martyr missions, jihadist recruitment videos and so-called martyr poems.” Nor was this his first encounter with MI5: “Two months before the port stop, in July 2015, the security services had viewed and assessed Ismail’s Facebook account. Simon Barraclough of the GMP told the inquiry: ‘The account contained 58 captures [photos] and this includes numerous images and videos of males in camouflage clothing with military weapons.’ … Yet Ismail was not apprehended in 2015. Instead, a counter-terrorism police sergeant examined the material and “concluded that it did not meet the evidential threshold for submission” to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the police said. And in a final twist, Declassified UK reported, despite having been summoned to testify to the inquiry, Ismail “was allowed to leave the country in August last year even after the police had detained him under the Terrorism Act and questioned him.” What a coincidence.

NATO proxies

In the last of the three articles on the Manchester Bombing inquiry, Declassified UK founder and editor Curtis wrote that NATO, the British military, and the government of thenPrime Minister David Cameron knew exactly who the “rebels” were whom they were assisting to overthrow Qaddafi—and kept right on providing them air support, and in many cases outright planning and coordinating their attacks, regardless. “In early September 2011”, wrote Curtis, “Cameron updated the House of Commons about the situation in Libya, telling MPs: ‘This revolution was not about extreme Islamism; al-Qaeda played no part in it.’ However, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) had assessed the month before that: ‘The 17 February Brigade is likely to be an enduring player in [the] transition’ away from Gaddafi’s regime and had ‘political linkages’ to Libya’s rebel leadership, the National Transitional Council. … The MOD assessment said, ‘Many 17th February Brigade fighters have affiliations with the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups, such as the Libyan Islamic Movement for Change (formerly LIFG).’” Among said LIFG affiliates were Ramadan and Salman Abedi, along with hundreds of other Manchester-based Libyan extremists.

That MOD assessment was made in August 2011, Curtis reported. Yet “Although NATO’s UN mandate allowed it only to protect civilians, the alliance continued attacking Gaddafi’s forces until the end of October 2011, two months after the fall of Tripoli. Gaddafi was lynched by rebels in his hometown of Sirte on 20 October.” Under the rule of NATO’s jihadists, Libya descended from the country with the highest standard of living in Africa, to a mediaeval hell-hole where slaves are traded in public marketplaces. It also became a key training ground and source of weapons for the LIFG’s fellow “moderate rebels” in the USA and NATO’s failed regime-change war on Syria.

Footnotes

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 13 July 2022