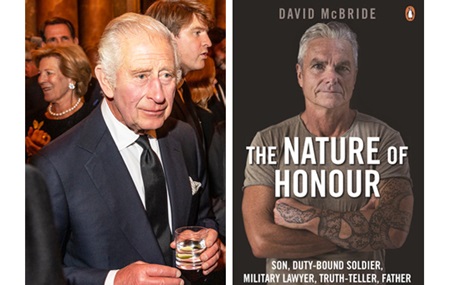

5 Dec.—Ever since charges were laid against him almost five years ago for leaking classified evidence of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan, former Army lawyer David McBride has always insisted upon having his day in court, even at the risk of spending the rest of his life in prison, rather than accept a pre-trial plea bargain. Only by going to trial, he believed, would he be able to “put the system on trial” before a jury of not a mere 12 of his fellow Australians, but all 25 million of them. In that, he has succeeded. In the end, stripped by the court of the documentary evidence he had intended to present in his defence, and denied the right even to argue that he had acted in the public interest, on 17 November McBride pled guilty to a reduced indictment and now faces a maximum 10 years’ jail (sentence to be determined in January 2024), down from the original 50 years. To achieve this result, however, the prosecution was forced to put forward, and the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory to accept, legal arguments that expose the ugly truth about how and for whom the power structures of this country really work. Like the sacking of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam by the British Crown five decades earlier, the McBride case once again makes explicit that for all Australia’s pretensions to democracy, according to both the letter and, whenever those power structures are threatened, the practice of the law, it remains in fact a mere colony, under the absolute and arbitrary rule of a foreign monarch.

The gist of the Crown’s case against McBride, was that a soldier has no right to act contrary to orders from his superior officers—even, as McBride did, to expose crimes to which those superiors had at the least made themselves accessories after the fact, by covering them up—because, as presiding judge Justice (sic) David Mossop put it, “There is no aspect of duty that allows the accused to act in the public interest contrary to a lawful order.” The defence’s argument that this overturned the heretofore universally accepted 1945 Nuremberg precedent, established during the trials of Nazi war criminals who were “just following orders”, was blithely brushed aside. The argument Mossop accepted in order to make this extraordinary ruling, as set forth by Crown prosecutor Trish McDonald, was that the oath of enlistment McBride—and every other soldier, sailor and airman—had taken was not to serve Australia as such, but rather that he would “well and truly serve Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, Her Heirs and Successors according to law … [and] resist Her enemies.”

“To interpret [the word] ‘serve’ to mean to act in the public interest”, McDonald said, “is to turn on its head service to king or queen. Nowhere in the oath does it refer to public interest or that a soldier must act in the public interest.” (Emphasis added.) Which is absolutely true— and staggering in its implications. As Sydney-based essayist and former senior New South Wales public servant Dr Bronwyn Kelly, founder of the non-profit organisation Australian Community Futures Planning, aptly summarised in an analysis published 28 November on Substack: “This amounts to an argument that the oath of enlistment in Australia’s armed forces is an oath to act against the public interest whenever it is contrary to the current monarch’s interest, or when she or he simply orders armed forces personnel to do so.” Or as she states the case even more succinctly in her headline: “So it’s out in the open at last—the Crown is the enemy of the People.”

‘Assumptions’ vs the letter of the law

The misconception that Australia is or ever was a true democracy rests upon certain widely held but incorrect assumptions. Among these, Dr Kelly writes, is generally included “one that suggests that the sovereign derives its authority from the people. Constitutional lawyer Helen Irving has assumed as much by saying that ‘The Constitution rests upon the sovereignty of the people … their consent is the ultimate authority for government … and a core part of the principle of democratic sovereignty is that power must not be derived from another source.’ This would imply that under our Constitution the people are a higher authority than the Crown and that the Crown must defer to their interests.” But alas, “the Crown itself (whether it takes the form of a king, a queen or an executive government) now assumes it has no obligation to serve or protect the people. It has no obligation to anything other than itself. And by extension the Crown’s implication is that its armies have no obligation to the people and their interests.”

Worse than that, Dr Kelly adds, interpreting the oath as McDonald and the court did, to mean that “to act in the public interest is to turn on its head service to king or queen”, is to assert “that by taking the oath a soldier is being offered a strictly binary choice between essentially opposed entities and there is only one choice they can make”—and therefore, “[they] are declaring that one of the ‘enemies’ the armed forces are bound by their oath to defend the Crown against is the people themselves. It is now out in the open that Australia’s armed forces aren’t there to protect and defend Australians, they’re there to protect and defend the king or queen, of a foreign country no less; and more than that, to take up arms against the people if she or he orders them to do so.” (Emphasis added.) Not something likely to have been fully considered, Dr Kelly notes, by any Australian soldier who had grown up in what they had assumed was a democracy, when they took their oath to serve the Crown. “It is likely that they would have thought they would be required to kill non-citizens whose actions might be threatening the legitimate interests of Australians”, she writes. “But it is unlikely that many soldiers who have faithfully sworn this oath were advised of the obligations implied by Ms McDonald—that, if so ordered, they would be required unquestioningly to turn their weapons on the citizens of Australia…. And if any did consider it and took the oath anyway, then we might worry about their fitness to serve in defence of Australians.”

And were all that not bad enough, everything said above of Australian Defence (sic) Force personnel is also true of the executive government (i.e. the Prime Minister and Cabinet), and indeed every member of Parliament both state and federal. Because as Dr Kelly notes, the oath they are “forced to swear before they can take up a seat offered by the people in a democratic election, is mostly identical to the oath for the armed forces. It too forces those who might seek office to further the public interest to swear no more than that they ‘will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, Her heirs and successors according to law’. There is nothing in the oath for elected parliamentarians that mentions the public interest. And now that we have seen a Commonwealth prosecutor push arguments on the court that basically suggest both parliamentarians and soldiers must disregard the public interest if the Crown or the Executive says so, it is clear at last that the form of state extant in Australia is one in which force is ranged against the people.” (Emphasis added.)

Déjà vu all over again

Perhaps the most infuriating aspect of all this, is that we as a nation have been here before, two generations ago—when the Crown, in the person of Queen Elizabeth II’s vice-regent, Governor-General Sir John Kerr, summarily dismissed the democratically elected government of Australian Labor Party PM Gough Whitlam on fabricated pretexts on 11 November 1975. Indeed, it seemed for a while that Labor, at least, had learned the lesson that our so-called democracy was a sham. For example one of the ALP’s rising stars, later Attorney-General Gareth Evans, observed in Meanjin magazine in April 1976 that “if the literal language of the Constitution were to be believed, the Governor-General had all the status and power of an Ottoman sultan. He could, for example, dismiss at will both Parliaments (s. 5) and Ministers (s. 64), refuse to appoint any Ministers at all (s. 64), allow Parliament to meet but one day a year (s. 5) and not spend any money when it did (s. 56), and take over the personal control, as commanderin-chief of the army, navy and air force (s. 68).” But alas, 48 years and one week after the Crown last unsheathed its claws, it is a Labor government at whose hands David McBride was forced to sacrifice his freedom in order to remind the nation of what it should never have forgotten.

Dr Kelly closes her essay with an appeal to all Australians to think through carefully what the outcome of McBride’s case means for them. “Who will serve them”, she asks, “if the armies they pay for and the executive governments they elect aren’t obliged to, or simply won’t, because the will of a sovereign that they do not elect is to line up that army against them?

“Good questions, all of which arise because of the Crown prosecutor’s candid admissions of the heinous purpose of our arrangements of state. But for these good and timely questions we should thank not the Crown prosecutor but the wonderful David McBride. Hopefully, because of his integrity and bravery, it is not too late for us to face them and build a truly democratic state in which the people are sovereign.” Hear, hear. In the meantime, David McBride’s own question to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, posed via the TV cameras as he entered court at the start of his trial—“Today I serve my country. … Who do you serve?”—has been well and truly answered.

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 7 December 2023