The House of Windsor claims “to remain strictly neutral with respect to political matters”, but the recently released “palace letters” prove beyond doubt this is a myth. Moreover, the letters confirm that the Queen intently followed every detail of the political events in Australia and, through her private secretary Sir Martin Charteris, communicated to Governor-General Sir John Kerr how Prime Minister Gough Whitlam could be dismissed. It is laughable to say the Queen did not know, particularly in the face of this new evidence. The Citizens Party’s longtime charge that the Queen sacked Whitlam in what was an Anglo-American coup is now further supported.

Now many journalists in the mainstream media acknowledge the coup. Peter Cronau, for example, a Gold Walkley award-winning journalist and ABC Four Corners producer, on 19 July tweeted, “There’s no doubt the Queen had considerable detailed prior knowledge of options being secretly canvassed. She appears to be part of the conspiring and the secret plotting for the overthrow of our elected government. And we thought she was only there to cut ribbons.”

John Menadue was head of the Prime Minister’s Department during the 1975 crisis. In a 21 July 2020 article at his Pearls and Irritations blog, he lists numerous reasons “to reject the Queen’s cover-up and the cover-up done on her behalf”. He reported that even on the day of the release of the Palace Papers, the National Archives of Australia continued to obstruct and mislead. It “tried to spin the contents of the letters” to favoured media before Professor Jennifer Hocking had a chance to look at any letter. She was forced to wait even though she was the only applicant subject to the High Court order.

In an 11 November 2015 media release, the Citizens Party (then Citizens Electoral Council) made clear that “Supply” was not the issue and that the coup was planned months beforehand. Prince Charles’s communications with Kerr over the Reserve Powers in September 1975 are confirmed in the letters. Serious investigators have known of the coup plot for years. As reported by renowned journalist John Pilger in 2014, “In interviews in the 1980s with the American investigative journalist Joseph Trento, executive officers of the CIA disclosed that the ‘Whitlam problem’ had been discussed ‘with urgency’ by the CIA’s director, William Colby, and the head of MI6, Sir Maurice Oldfield, and that ‘arrangements’ were made.” It’s noteworthy that Sir John Kerr had been an intelligence agent in WWII and played a founding role in the CIA-backed Australian Association for Cultural Freedom.

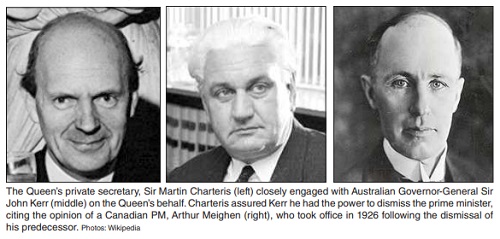

The Queen’s private secretary, Lieutenant Colonel the Right Honourable Sir Martin Charteris, KCB, KCVO, OBE was “an experienced, wily and polished public servant exuding the air of effortless superiority—the hallmark of the British aristocracy”, wrote former Australian diplomat Tim McDonald in a 17 July article for Pearls and Irritations. McDonald added, “By way of explanation, my job as Official Secretary in the Australian High Commission involved liaison with the palace. I had extensive dealings with Charteris.” McDonald outlines how the British Monarchy functions in practice, primarily to serve “British interests”.

The letters

In his 14 September 1974 letter to Kerr, Charteris described the Labor Party as a “Radical Party coming to power after many years in the wilderness of opposition”. Charteris then advised Kerr, “I am sure your influence will be most beneficial in improving the situation”. After a reference to developing “a good relationship” with the abovementioned Menadue who had just been appointed head of the Prime Minister’s Department, Charteris assured Kerr that “the Queen is deriving pleasure and interest” from his letters, “and that, of course is the main object of the exercise!”

In his 3 July 1975 letter to Charteris, Kerr attached a newspaper clipping from the Canberra Times of the following day: “The ultimate guardian of the Constitution, of the rule of law, and of the customary usages of the Australian Government in a time of crisis is the Governor-General, who has certain clear powers to check an elected government. He normally acts on the advice of his ministers but there are occasions when he need not seek or accept that advice. He could, for good and sufficient reasons, revoke the commissions of a Prime Minister or of other ministers.” (Emphasis added.)

The Queen was not just taking a partial interest. She intently followed every detail. Charteris’s 30 July 1975 letter to Kerr makes this clear: “Both these fascinating accounts [in two letters including one on the ‘loan crisis’] of what has been going on in Canberra have been read with the greatest interest by The Queen. Indeed, Her Majesty’s interest in them has to some extent delayed this reply.” In the same letter Charteris said, “Mr Whitlam, as you say, is a great campaigner and I suspect will be very difficult to beat in a general election.”

In his 4 November 1975 letter to Kerr, Charteris advises Kerr he has power to dismiss the prime minister: “When the reserve powers, or the prerogative, of the Crown, to dissolve Parliament (or to refuse to give a dissolution) have not been used for many years, it is often argued that such powers no longer exist. I do not believe this to be true.”

The following day Charteris sends another letter to Kerr and quotes a Canadian prime minister, Arthur Meighen, on the powers of the governor-general: “It is [the governorgeneral’s] duty to make sure that parliament is not stifled by government, but that every government is held responsible to parliament, and every parliament held responsible to the people.” In this 5 November letter, Charteris clearly encourages Kerr to go ahead with the dismissal. After assuring Kerr that he does have reserve powers, Charteris states: “If you do, as you will, what the constitution dictates, you cannot possible [sic] do the Monarchy any avoidable harm. The chances are you will do it good.”

In addition to the numerous letters from Sir Martin Charteris, the palace letters include several letters from William Heseltine who at the time of the constitutional crisis was the Queen’s assistant private secretary. On a Buckingham Palace letterhead, Heseltine wrote to Kerr on 25 February 1975 making clear the Palace’s disapproval of Prime Minister Whitlam: “I am sorry to hear that the Prime Minister is still exacerbating Commonwealth-State relations.” This comment was a response to Kerr’s 10-page letter to Buckingham Palace on 19 February in which he detailed Whitlam’s “bad relations with four of the States”. Kerr stated, “the Prime Minister is the author of many of his own troubles … as he finds it difficult to conceal his contempt for much of what the Premiers say and do and for what they believe in.”

Professor Hocking in a 24 July article at Pearls and Irritations notes how Prime Minister Whitlam was deliberately left out of the entire process. This is no surprise. The Whitlam government’s determined efforts to assert Australian sovereignty upset the Anglo-American establishment, and he had to go. Whitlam exposed war crimes and threatened to close the secretive US-run intelligence facility at Pine Gap, near Alice Springs. He intended to “buy back the farm” and control Australia’s vast mineral resources for national development. As the longtime largest shareholder of Rio Tinto, the Queen was not amused.

By Jeremy Beck, Australian Alert Service, 29 July 2020