"Fascism should more appropriately be called corporativism, because it is a merger of state and corporate power.”

—Italian Fascist “philosopher” Giovanni Gentile, The Doctrine of Fascism, 1932.

The federal Parliament’s recently launched inquiry into large fund managers’ cross-ownership of Australian companies is welcome, and long overdue. Whilst the Liberal government plainly intends it to serve mainly as a platform for yet another attack on the industry superannuation fund sector, the inquiry nonetheless presents a valuable opportunity to expose giant foreign fund managers’ increasing use of their influence to extort compliance with their own policy agendas, in particular the suicidal push towards a so-called “net-zero carbon economy”, from corporations and governments alike. Their ability to do so, something even bankers’ puppet Prime Minister Scott Morrison has admitted, is also an excellent argument for re-establishing a publicly owned national bank to break the economic stranglehold of private capital once and for all.

Parliament announced in a 2 August media release that the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics was commencing an “inquiry into the implications of capital concentration and common ownership” in Australia by “institutional investors”, such as banks, superannuation funds, investment funds, and hedge funds. Common ownership, the release explained, “refers to when a fund or collaborative funds simultaneously own shares in competing firms”. Liberal Party MP Tim Wilson, who chairs the Committee, described the inquiry as “urgent” in light of recent testimony to Parliament by Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) Chairman Rod Sims that whereas common ownership poses threats to competition when it reaches 10 per cent, in some sectors it has already reached 30 per cent. “We don’t want a stock exchange where a handful of ‘mega funds’ make all the decisions, and ordinary investors are locked out and higher costs are paid by Australians”, Wilson said. “Common ownership’s flow-on risks higher prices and collusion, corporates imposing public policy agendas while bypassing democracy, and disempowering ordinary investors. The law shouldn’t empower capital over citizens and that’s what we’ll be inquiring into.” (Emphasis added.)

For several years now Wilson has been the front-man for the Liberal Party’s campaign to hobble the not-for-profit industry funds, which continually out-perform their largely bank-owned “commercial” counterparts.1 An exclusive in the 2 August Australian Financial Review suggests that this new inquiry is intended to be more of the same. “Government members are anxious about the rising power of unionbacked industry superannuation funds and their influence in picking company directors, voting at shareholder meetings and potentially prosecuting political agendas”, AFR reported. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg effectively confirmed this in his letter to Wilson approving the inquiry, in which he wrote: “Given the potential broader implications for investors and the economy, I share your commitment to ensuring the consequences for capital concentration in our superannuation sector are well understood.”

Investment cartel

The opposition Labor Party, however, intends to take a different tack. “Passive index funds run by [US-based investment managers] BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street which typically own about 10 per cent to 15 per cent of Australia’s listed stocks, will also face scrutiny from Labor during the inquiry”, the article continued. “The inquiry’s deputy chairman, Labor MP Andrew Leigh, has published research raising concerns about ownership concentration across listed companies … [which] suggested the world’s largest asset managers, such as BlackRock and Vanguard, and local super fund giants may be inhibiting competition by owning large stakes in rival businesses.”

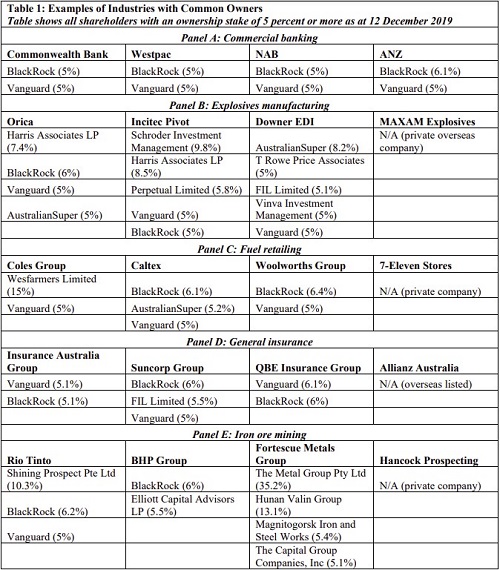

Leigh’s research, co-authored with Australian National University economist Dr Adam Triggs for Germany-based nonprofit research body the Institute of Labour Economics (Institut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, IZA),2 reveals such a level of common ownership that it might better be termed cartelisation. “Among firms where we can identify at least one owner, 31 per cent share a substantial owner with a rival company”, they wrote. Having analysed 443 industries, whose combined revenue represents around 70 per cent of Australian gross domestic product (GDP), “we identif[ied] 49 that exhibit common ownership, including commercial banking, explosives manufacturing, fuel retailing, insurance and iron ore mining”. Fortynine out of 443 (about 11 per cent) might seem a small proportion, although the number would likely have been much higher but for want of data. But even so, they wrote, “Across the Australian economy, common ownership increases effective market concentration by 21 per cent”, because the industries with common owners “are among the largest in Australia, collectively representing 36 per cent of total revenues across the 443 industries”. And by far the biggest common owners, in what are already the most concentrated economic sectors, are BlackRock and Vanguard. “In banking, BlackRock and Vanguard are among the top three investors for all four major banks”, Leigh and Triggs reported. “In explosives manufacturing, Vanguard is a common owner in Orica, Incitec Pivot and Downer EDI while BlackRock and Harris Associates are common owners of Orica and Incitec Pivot. Vanguard is a common owner in three major fuel retailers—Coles Group, Caltex and Woolworths Group—with BlackRock a common owner of both Caltex and Woolworths Group. In general insurance, BlackRock and Vanguard are common shareholders across Insurance Australia Group, Suncorp Group and QBE Insurance Group. In iron ore mining, BlackRock is a common owner of both Rio Tinto and BHP Group.”

State Street, the third of the USA’s (and the world’s) “Big Three” largest fund managers, is also a significant common owner in Australia, albeit it only registered eight “substantial shareholder listings” versus 80-plus apiece for both BlackRock and Vanguard. Leigh and Triggs were forced to drop those holdings from their analysis, however, because thanks to Australia’s lax corporate disclosure laws “we have been unable to obtain a breakdown of State Street’s custodian and fund management businesses in Australia”, making it impossible to distinguish its own shareholdings from those it merely manages on others’ behalf.

Undue influence

Leigh and Triggs’ research focuses on the anti-competition aspect of common ownership, namely that “In the presence of a common owner, the [‘rival’] firms are more likely to cosily divide the market than they are to embark on a risky price war”, including in extreme cases by actively forming cartels, of which previous studies suggest only one in five is ever discovered by regulators. Whilst this is certainly true, by far the greater danger is what Wilson correctly described as “corporates imposing public policy agendas while bypassing democracy”—something which BlackRock in particular is already doing in Australia and around the world, working with the Switzerland-based Bank for International Settlements (BIS), billionaires’ club the World Economic Forum (WEF) and related institutions in an attempt to establish a global bankers’ dictatorship on the pretext of combatting “climate change”.

BlackRock’s overt efforts in this direction date back to 2019, when it announced that it would no longer invest any of its approximately US$7 trillion funds under management in coal companies. As the Australian Alert Service reported at the time, at the August 2019 US Federal Reserve-sponsored annual central bankers’ summit at Jackson Hole, in the US state of Wyoming, BlackRock called for monetary-policy “regime change” to give unelected central bankers control over government spending so they could enforce “green” policy.3 This move was apparently coordinated with the BIS, which in January 2020 released a discussion paper titled “The green swan: central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change”, which laid out a plan to achieve exactly the monetary regime change BlackRock had called for.4 Since then BlackRock and Vanguard have thrown their weight behind the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, “an international group of asset managers committed to supporting the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner” according to its website, which was established in December 2020 and as of this writing has 128 members. This and other investment cartels are already active in Australia, and are actively blackmailing governments and corporations into changing their economic policies and investment strategies, upon pain of being starved of capital through what amounts to a boycott of their bonds and/or shares.5<

Political litmus test

With a federal election due no later than September next year, but probably some months sooner, the House Economics Committee inquiry is shaping up as a useful gauge of both major parties’ policy intentions. Labor constantly harps on the government’s lack of firm targets to meet the carbon dioxide emissions-reduction commitments it took on under the 2015 “Paris Agreement”, aimed (ostensibly) at limiting so-called manmade global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. Yet Labor is also increasingly internally divided over the extent to which it will prioritise retaining its traditional blue-collar support base, whose livelihoods tend to be dependent upon mining, manufacturing and other “carbonintensive” industries, on the one hand; and appealing to “environmentally conscious” voters primarily involved in the inner-city-based service economy, on the other.

The Liberal Party likewise has a balancing act to perform, in that it must cater rhetorically to its generally much more “climate-sceptic” base, while delivering policies which advantage its suite of corporate donors, most of which are either piling into lucrative “carbon trading” initiatives and taxpayer-subsidised “clean energy” projects, seeking to avoid being blacklisted by BlackRock, or both. And as reported 10 August by the AFR, PM Morrison has flagged the latter as a potential excuse for capitulating to the “net zero” agenda, having stated that day that he is “very aware of the significant changes that are happening in the global economy. I mean, financiers are already making decisions regardless of governments about this.”

“I want to make sure that Australian companies can get loans. I want to make sure that Australians can access finance”, the AFR quoted Morrison. “I want to make sure our banks are well financed into the future so they can provide the incredible support [sic!] they provide to Australians buying homes and all of these things,” he said—referring, the article noted, to the fact that about one third of the Australian banking system’s mortgage lending is funded by offshore borrowings. “The world economy is changing”, Morrison went on, and “we need to continue to change with it to remain competitive”.

That much, at least, is true, if not the way Morrison meant it. Australia’s own history proves that with a national bank, such as the original Commonwealth Bank of Australia, our nation’s economy does not need foreign capital at all, and indeed functions better without it. As Queensland Liberal Party Senator Gerard Rennick put it in a speech to Parliament this month, a national bank can issue sovereign credit backed by the nation’s sovereign wealth, effectively “printing money” to fund nation-building infrastructure projects, without causing inflation. “If you print and build”, Rennick said, “you’ll increase the supply of essential services” like water, electricity and transportation. “Not only does that raise revenue for governments”, he said, “which then means you’ve got fewer taxes going forward; it increases the supply of central services and it pushes down the cost of doing business. So it will make Australia much more competitive … with other countries.” (Emphasis added.)

Whilst most Liberals may not subscribe to Rennick’s view (though some certainly do), well-placed sources have told AAS that the idea of public banking is gaining ground among the dominant faction of the National Party, making it a potential point of contention when the two parties next renew their coalition agreement.

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 18 August 2021

Footnotes