The colourful expatriate American politician King O’Malley preached the idea of State banking on a nationwide basis at the first ever Australian federal election in 1901. By 1905 it was in the party platform of the federal Labor Party and in 1907 the Liberal Acting Prime Minister, Sir John Forrest, told a State Premiers Conference at Brisbane that he had in mind (and it had been urged on the government) a Post office Savings Bank for all Australians: “And what a splendid thing it would be for the people of Australia.” His plans were handed to the Parliamentary draftsman in order to prepare a bill, but no bill eventuated; meanwhile, the Labor Party put the national bank proposal into its fighting platform in 1908, and concrete plans for a Commonwealth Bank started to take shape. In 1911 Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher tabled the Commonwealth Bank Bill. After eight weeks of debate it passed without amendment, with the power to conduct every kind of general banking business, including through post offices.

Recounted here is the history of the Commonwealth Bank’s initial post office-based savings bank function. For the full story of the fight to establish the bank as a national bank, in the image of the First Bank of the United States, founded by King O’Malley’s hero US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, see “The Australian Precedents for a Hamiltonian Credit System”, a presentation by Citizens Party leader Craig Isherwood to a 2015 Citizens Party conference, available under “Publications” on our website.

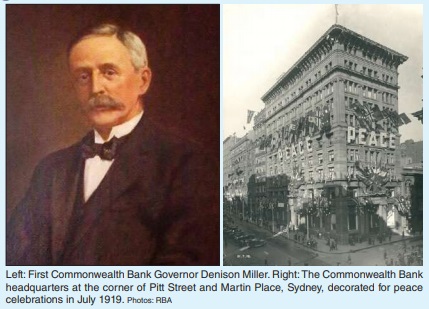

As recounted in The Commonwealth Bank of Australia: A Brief History of its Establishment, Development and Service to the People of Australia and the British Empire under Sir Denison Miller, by C.C. Faulkner (1923), the Commonwealth Bank began its operations with its Savings Bank business, prior to commencing other general business.

In 1901, the Postmaster-General’s Department had been established to unify state-based postal and telegraph services into one federal agency. With passage of the Commonwealth Post and Telegraph Act in June 1902, all post office workers were employees of the Commonwealth. The idea to establish the new Commonwealth Bank’s branches at existing local post offices made perfect sense. At the time, state banks run by state governments conducted virtually all their savings bank business at local post offices, by arrangement with the federal government, but post offices were released from this agreement in 1913 to make way for the Commonwealth Bank.

Although the Commonwealth Bank Act 1911 gave the bank the power to raise capital worth £1 million, the bank’s Governor Denison Miller realised it was not necessary. “The Act provided that the security of the whole Commonwealth should be behind the Bank, and the Governor perceived that with this security the cash capital provided need not be called up. Such capital as might be necessary would become available simply by setting the machinery of the Savings Banks in motion.”

State banks

The bank’s operations commenced first in Victoria because the State Savings Bank had vacated post offices which it used as agencies, leaving hundreds of trained post office staff to run Commonwealth Bank activities. On 15 July 1912 the Commonwealth Bank opened in 489 Victorian locations. The Faulkner history reports: “While the Commonwealth Bank Act was before Parliament, the State Governments saw that the post offices would be required for the Commonwealth Savings Banks, and they had already begun to make arrangements to carry on their agencies in other premises. … The post offices where the people’s banking had always been transacted, were available for the new Bank before it had yet come into being.”

Queensland was next, starting 16 September of the same year, with an agency at the General Post office in Brisbane and 194 local post offices. The Northern Territory, which had no State Savings Bank facilities, followed closely behind Queensland. By Act of Parliament the government of Tasmania merged its State Savings Bank with the Commonwealth on 1 January 1913; almost its entire staff was shifted over to work for the Commonwealth Bank, with business taking up at the Hobart state bank branch and 147 post offices.

From 13 January 1913, the Commonwealth Savings Bank opened for business in post offices in New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia. “One of the Governor’s first cares”, wrote Faulkner, “was to provide Savings Bank facilities for sections of the community which had not been served in the past.”

Before commencing the Bank’s postal operations, Denison Miller held a conference of post office officials who ran state bank savings facilities and together they drew up regulations for the conduct of the bank. Talk of inevitable competition between state banks and the new Commonwealth was rampant, with speculation assuming that one or the other would eventually be driven out of existence, but Governor Miller made clear he would have no part in such a contest. He declared that the “prosperity and stability of the Commonwealth and of the States were mutually inter-dependent” and fixed his bank’s interest rate slightly below that of the State Savings Banks so as not to encourage a rush of deposit transfers. (During times of tight money markets, such as during WWI, the Commonwealth resisted raising rates, which “had a marked effect in keeping down interest rates to the benefit of the commercial and business community throughout Australia”, wrote Faulkner.)

In the course of events the Queensland Government Savings Bank merged with the Commonwealth Bank in 1920, which brought all government banking business into the fold and absorbed all staff. This included an arrangement whereby the bank transferred to the state government up to 70 per cent of increases in depositor’s balances, receiving in return State Government Securities to the same value at current interest rates, with the right to draw down the deposits from the Queensland Treasury if necessary. The state governments of Tasmania, WA and SA also began banking with the Commonwealth.

The Commonwealth would later take over the collapsing Government Savings Bank of NSW and State Savings Bank of Western Australia after they were impacted by the 1931 Depression, and step in to rescue the collapsing State Bank of Victoria in 1991, at the start of its 150th year. (“State premiers should unleash the power of state banking!”, AAS, 16 Sept. 2020.)

The travelling bank

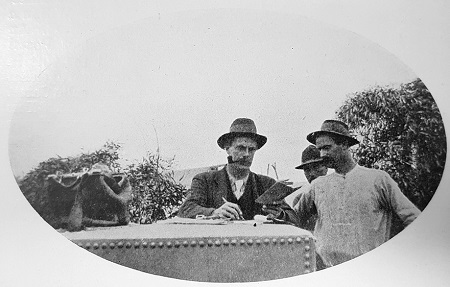

While the Trans-Australian Railway was being built prior to WWI, connecting existing WA and SA lines to form the trans-Continental Railway, the Commonwealth Bank provided banking facilities to the workers. Starting in February 1913, arrangements were made to fit two railway cars out as savings bank branches to be staffed by a railway pay-master, savings bank officer and a postal official. Staff travelled by road until two rail cars were ready, to cater for workers along the WA length of the line. On the SA side, postal agencies were established at several camps along the line along with a travelling post office involving a postmaster and savings bank agent. This service, called the Travelling Commonwealth Savings Bank, extended across the Nullarbor Plain. The lengths they went to stand in stark contrast to today’s reluctance to provide banking services to remote and regional communities. Faulkner reported: “Every fortnight the Government paymaster drove out with his team of four mules and his boxes of money. Behind him, riding a horse or a camel, came the travelling agent of the Commonwealth Savings Bank. When the paymaster settled down for business on the broad earth that is Central Australia, the banker would sit down, too, and take into safe custody part of the workers’ earnings. Sufficient for him to conduct business was the tailboard of a buggy, the mudguard or running board of a motor car, the seat of a railway trolley, the top of a 400-gallon iron tank, or the platform of the paymaster’s train. Or his counter might be a mail bag, chaff sack, or sheet of paper spread out on the ground, his thigh the writing table. His customers knelt on the ground to sign their deposit slips.” In three years, one bank officer travelled 60,000 miles across desolate terrain! Workers built up savings accounts or invested in war bonds and savings certificates, rather than blowing their wages on two-up or poker. By the time the railway was finished in October 1917, many workers reported they could buy a home or did not have need of a pension, thanks to the banking facilities they were provided.

Following the successful launch of the savings branches, with excellent take-up of new deposit accounts, on 20 January 1913 the General Banking Department of the bank opened in all Australian capitals, Townsville and London. All Commonwealth Government bank accounts were transferred across to the Commonwealth Bank. At the opening of the bank’s headquarters in Sydney, Governor Miller made a five-minute speech in which he declared: “The Bank is being started without capital, as none is required at the present time, but it is backed by the entire wealth and credit of the whole of the Commonwealth of Australia.” The bank’s success, he stressed, will “depend on the continued support of the people whose Bank it is, and in whose interests no effort will be spared to make this national institution one of great strength and assistance in maintaining the financial equilibrium on safe lines, so that its expansion may be concurrent with an ever increasing volume of wealth of the Commonwealth of Australia.”

Concluding a speech at the Royal Historical Society of Queensland marking the Jubilee anniversary of the Commonwealth Bank in 1962, C.M. Taylor summed up the bank’s contribution to average Australians: “Competing with the other banks on equal terms, at no time taking advantage of Government aid or concessions, it has provided banking services for hundreds of thousands, even millions, of Australian citizens, school children, wage earners, home builders, primary producers, industrialists, executives, pensioners, manufacturers, and in doing so, has earned the gratitude of a nation.”

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 30 June 2021