The public hearings of the Senate inquiry into Sterling First, conducted on 16 and 18 November 2021, exposed the systemic failings of the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). ASIC did not lift a finger to prevent the loss of the life savings of over 140 elderly victims of the disastrous Sterling First scheme, and now witness testimony and explosive new evidence has destroyed the central pillars of ASIC’s defence of its appalling regulatory neglect.

‘ASIC did everything it could’

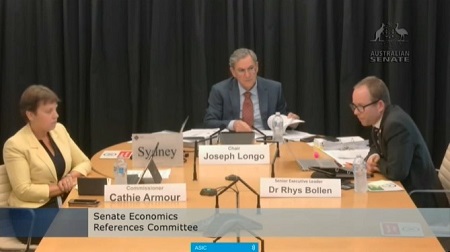

ASIC’s submission claimed the regulator had “taken what action it could” in regards to Sterling First, a premise maintained by ASIC Chair Joe Longo in the inquiry hearings. However, key witnesses contradicted ASIC’s claims.

The testimony of criminologist and advocate for Sterling First victims, Denise Brailey, revealed that ASIC has been untruthful regarding key dates of ASIC’s actions. Brailey’s evidence, gathered over her two year investigation into the Sterling First matter, exposes ASIC’s intention to conceal the extent of its regulatory negligence from the public and the parliament.

In his opening statement, Niall Coburn, a High Court barrister and former investigator at ASIC, recommended that because of the “maladministration involved”, the parliament should recommend Sterling First victims be compensated. Notably, during Coburn’s thirteen years at ASIC, where he ran teams as a senior investigator and principal lawyer, one of his bosses was none other than Joe Longo, who was formerly ASIC’s head of enforcement from 1996-2000.

Coburn testified that the facts of the Sterling First case indicated that “ASIC failed to act decisively when it received very serious information” and “failed to take appropriate action within its powers to stop this scheme”. Coburn demolished ASIC’s claims that it had “taken what action it could”, by referring to sections of the Corporations Act which explicitly gave ASIC power to intervene. ASIC is empowered to use injunctions for the preservation of assets, which Coburn testified he had used many times to stop frauds.

Coburn testified that there was no explanation as to why ASIC “failed to act at certain important junctures”. Coburn was perplexed that ASIC did not investigate or conduct interviews after it received a complaint about Sterling from Western Australia’s Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety (DMIRS) in March 2017, when there were already “serious material nondisclosures of risks to the elderly investors”.

Coburn questioned why it took six months for ASIC to issue a stop order (which Coburn believed was an inappropriate measure because it was a “mere administrative mechanism”), and why it took ASIC almost a year to start a formal investigation into Sterling. Coburn observed that “the fraud was allowed to spread its tentacles and accumulate more money from innocent investors … If you’re waiting six months to a year, then you’re going to have a lot of bodies on the street.”

Coburn testified that as head of an investigative team at ASIC, he would have immediately started an investigation and interviewed witnesses after receiving the complaint from WA DMIRS. “These are elderly investors, so it doesn’t matter what you’re working on: vulnerable investors go to the top of your list. That is within ASIC; that is most regulators internationally now. There’s an emphasis to protect the elderly, and this scheme is really an elderly abuse scheme … it is incredible, honestly, that ASIC would wait a year to commence an investigation.”

Notably, Longo emphatically insisted to Senators several times that Sterling First was not a Ponzi scheme. Awkwardly however, Longo then had to backtrack shortly thereafter after receiving a note from ASIC executive Dr Rhys Bollen: “I’ve just been passed a note to say that the KPMG report may be looking at the Ponzi aspects in more depth”, he conceded. “We are waiting for a further report on that. But certainly, at the beginning, we don’t think it was a Ponzi scheme.”

The elderly victims of Sterling First were told by the schemers that their life savings would be kept safe in a trust. Longo stated: “It’s perfectly understandable, because of the use of the word ‘trust’ in the documents, they might have thought they were putting money into a dedicated stand-alone trust account that was in their name and that their money was preserved in that trust account”; however “[t]hat’s not how this was structured”. Longo insisted again that Sterling victims were investors, essentially brushing off the significance of the trust. However, Niall Coburn contradicted Longo’s apparent nonchalance: “The trust issue was very relevant”, he said. “It’s not what Mr Longo thought that a trust should be or what I think a trust should be; it’s what the investors were told … it was misrepresented to them”. Coburn stated that if ASIC had investigated, it would have been evident that elderly victims “had been sold a dog and that this firm has got their money, which was supposed to be held in trust, and then you look at the bank accounts and see it’s going out of trust … That would be enough to get an injunction, because they’re not explaining what they’re doing with the money … it’s not that complicated”.

‘ASIC didn’t have the evidence it needed to act earlier’

In response to Coburn’s testimony that ASIC should have used its powers to issue an injunction in relation to Sterling First, both Longo and ASIC have insisted that ASIC did not have the evidence it needed to take early injunctive action. However, according to Coburn, the internal threshold for ASIC to act is very low, as the Corporations Act only requires an investigator to have a “mere suspicion” of a contravention. Coburn stated that the complaint from WA DMIRS could have been used in an affidavit before the Federal Court to assist in the application for an injunction.

Coburn testified that with these “fraudulent schemes” it is vital that ASIC acts quickly and early, to “freeze everything and stop everything … You’ve got to be fast, because these fraudsters are really good.” Despite Longo’s protestations that an injunction was a “drastic remedy” that would “have the effect of ending a business”, Coburn stated that an injunction “doesn’t have to be advertised”—an interim injunction could maintain confidentiality or be conducted in camera, so as not to hurt a business while ASIC assessed the situation.

It was evident that Longo was not pleased by Coburn’s contradictory testimony, which Longo claimed was “rather extravagantly expressed”. Longo stated that in 2017 ASIC “did not have admissible evidence” for an injunction, claiming that in 2017, “there was no evidence of fraud.” Notably, it would be difficult for ASIC to find evidence of fraud, when it did not bother to do any investigation.

Despite Longo’s claims, there is a laundry list of events where ASIC failed to act on Sterling entities. For example, Longo admitted that in February 2013, ASIC had placed a stop order on Theta, as the responsible entity of the Rental Management Investment Trust, which would eventually become the Sterling Income Trust. However, Longo emphasised that this product had nothing to do with the rentfor-life scheme and therefore didn’t change ASIC’s views on its actions.

On 21 October 2021, the Senate ordered the production of internal documents regarding ASIC’s handling of the Sterling First matter. These documents were finally tabled almost a month later, days after the public hearings had occurred, which (conveniently for ASIC) prevented their being examined and pursued by Senators. These documents catalogue an early list of complaints ASIC had received in relation to the Sterling Group, including a February 2015 complaint lodged by the Financial Services Ombudsman. In what would be a horrifying revelation for the victims who were subsequently drawn into Sterling, the documents show that ASIC decided not to take action, despite noting that Sterling had “likely engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct”.

In September 2016, ASIC lodged a complaint from an investor who had purchased shares in one of the Sterling Group’s many companies, but now could not get their money back. Between September 2016 and January 2017, ASIC reviewed the Sterling Group’s companies and their websites, including Sterling First, Sterling Income Trust and Sterling New Life.

Despite this scrutiny, Longo testified that it was not until the March 2017 complaint from WA DMIRS that ASIC saw the “stapling” of the rent-for-life leases and the managed investment scheme. Longo claimed that until March 2017, the “connection did not become visible to [ASIC] in any meaningful way”. However, one of the documents ASIC reviewed between September 2016 and January 2017 “[c]learly shows [a] link between investment and sales of retirees’ properties and leases”, according to ASIC’s own documentation. Additionally, ASIC also reviewed the ‘Sterling New Life Sales Representative Information Package’— which reveals that ASIC had all the information it needed to act, but deliberately chose not to.

‘Sterling First was a property matter and therefore out of ASIC’s jurisdiction’

The documents produced under order of the Senate reveal that in June 2015, a report was lodged by an ASIC staffer regarding concerns over a Sterling New Life advertisement. The advertisement promoted free seminars on “property co-ownership” and was aimed at retirees, promising very high interest returns using “first mortgage security on properties”. The ASIC staffer thought that Sterling may have been providing unlicensed financial advice, and was concerned about possible misleading or deceptive conduct. However, ASIC decided not to act because after reviewing Sterling’s advertisement and website, they believed that it did not involve a financial product; rather “it appeared the company held a real estate license and was offering real estate investment advice”.

ASIC has persistently claimed that it believed Sterling First was a property matter and therefore out of its jurisdiction. For example, as recently as 28 February 2020, ASIC Commissioner John Price told a parliamentary hearing that the Sterling Group was promoting real estate, therefore “unless there’s some sort of investment structure around it so that we can get a jurisdictional anchor, we don’t have the jurisdiction.”

However, Denise Brailey testified that “ASIC knew from the advertisements and promotional ads this was a call to sign up tenants. … The financial product warranted a trust account, had a PDS [Product Disclosure Statement, a legally-required document for investment products] and therefore fell under ASIC’s jurisdiction.”

Niall Coburn confirmed: “You don’t look at the cat, you look at the legs and the way it walks. What a fraudster does is to dress something up so that it looks good”, but looking behind it reveals what is happening with the money. “This was a pool fund and it was clearly within ASIC’s jurisdiction … it would have taken three days to work out … the idea that it was tenancy law and not within their jurisdiction—from a consumer protection point of view, I honestly can’t see why they saw it as outside their jurisdiction and a separate product.”

Notably, inquiry testimony from the Financial Planners Association revealed that schemes such as Sterling First had typical hallmarks, as “a highly leveraged property investment scheme that is sold through advertising and seminars”. The FPA suggested ASIC should look closer at these schemes, because “there is a consistent nature to these types of products losing significant amounts of investors’ hard-earned money, particularly retirement savings”.

‘ASIC doesn’t interfere with commercially flawed business models’

During the inquiry, Senators were baffled that although ASIC found serious material nondisclosures and defects in Theta’s PDS in June 2017, ASIC permitted the company to just re-write a new PDS and carry on with drawing elderly people into the scheme. A Federal Court would later find that Theta’s new PDS was also defective.

In the inquiry hearing, ASIC executive Dr Rhys Bollen admitted that in order to form a view about whether a PDS was defective, ASIC would need to conduct analysis of the underlying product and see how it would generate the returns it promised. Senator Louise Pratt was confounded that ASIC would regulate by just requiring Theta to re-write its PDS, when ASIC had “acknowledged that their business model is unviable”. Longo replied: “That’s how the system works though”, sticking to the same excuse ASIC has used for years when confronted with the disastrous consequences of its regulatory failure; according to Longo: “We don’t regulate the performance of managed investment schemes”. Longo claimed that the Sterling First scheme “just didn’t go to plan … What went wrong here was that the business model was far too ambitious. They were looking for returns that we now know were not achievable, and the costs of running this business were high.” Senator Paul Scarr, formerly a corporate lawyer, said that rather than “ambitious”, he viewed Sterling’s expected rate of returns as “totally unrealistic”. Niall Coburn described them as “misleading”.

In ASIC’s submission to the Sterling inquiry, it quoted itself fronting a 2009 Senate inquiry initiated after the catastrophic collapse of Storm Financial: “Consistent with the economic philosophy underlying the FSR [Financial Sector Reform] regime, ASIC does not take action on the basis of commercially flawed business models.” Senator Pratt repeated this quote to Niall Coburn, who said “With the greatest respect, that is actually incorrect. Whoever told you that has misled you.” When Pratt said she was reading from ASIC’s submission, Coburn answered: “Well, it’s just not true, because what you do as an investigator is you look at all the facts”, such as Sterling’s “material and serious non-disclosures to investors”. Coburn stated: “Whether you call it a model or whatever you call it, it’s all the same thing. It’s misleading and deceptive fraud. That’s it. So if someone tells you that we don’t do it because it’s the model or we don’t interfere with the firm, that’s not how it works. What works is what the investors are being told. You look at their complaints, you get the evidence and, if you need to kick in a door, then you kick in a door.”

By Melissa Harrison, Australian Alert Service, 24 November 2021