A Senate inquiry examining the current capability of the Australian Public Service (APS) has issued a scathing report on the destructive impact of outsourcing public sector work. The final report issued November 2021, “APS Inc: undermining public sector capability and performance”, notes the significant impact of the Coalition government’s 2015 introduction of a cap on public service employees, beyond the downshift in public service capability already in motion. In contrast with the report’s findings, the Coalition MPs on the Finance and Public Administration References Committee which conducted the inquiry, vowed in a dissenting report to continue the slash and burn “reform” that brought the public sector to this point in the name of fiscal sustainability. The inquiry was chaired by ALP Senator Tim Ayres.

The Senate investigation took aim at the impact of government policy on the public service, building upon the assessment of the 2018-19 Thodey Review of the APS, which found the service “ill-prepared” for the future challenges Australia would face due to long-running underinvestment— something which has been proven in spades throughout the pandemic crisis.

Labour hire

The outsourcing of public service roles, dubbed “privatisation by stealth”, is a major contributor to the collapsing capability of the public service, according to the final report of the inquiry.

Submissions from policy institutes, the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU), employee associations and many others, noted the adverse impacts of the Average Staffing Level (ASL) cap as a budgetary constraint. By capping the number of staff that can be recruited (measured as “full-time equivalent” employees to account for part-time staff), the cap was a “key driver” of the “explosion” in external labour hire and consultants.

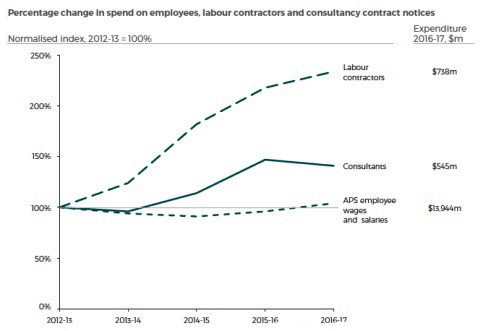

The Inquiry, like the previous Thodey Review which said the cap had “led to divestment in analytical capability”, recommended abolishing the cap. The CPSU noted that spending on external personnel contracts had increased by over 600 per cent from 2013 to 2020, while budget expenditure on public sector salaries increased by only 10 per cent.

No centralised figures of outsourced labour are kept, and there is very little transparency regarding the process. One submission to the inquiry indicated that one in five people working in federal government departments were employed on external contracts or through labour hire firms; almost 40 per cent of staff employed by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) in April 2021 were labour hire and contract workforce, with some teams being “fifty-fifty or more labour hire”, and in some sectors reaching two-thirds. At the DVA, a significant increase in claims, caseloads and backlogs has arisen since introduction of the ASL cap.

Many labour hire firms utilise “complex, transnational corporate structures that are designed to reduce and avoid taxes”, according to a submission from the Centre for International Corporate Tax Accountability Research (CICTAR).

Opaque ownership structures can create conflicts of interest. Firstly, when separate companies owned by the same parent company compete against each other for tenders there may be implications for agencies that must abide by Commonwealth Procurement Rules. CICTAR provided examples of multiple companies owned by the same multinational group, all used by the Department of Health and other government agencies. Secondly, there is a serious conflict of interest where an agency regulating certain entities is staffed by the same workhire cohort as the entity itself. For example, the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (ACQSC), which monitors the quality and provision of aged care, acquires a “significant portion” of its staff from the same labour agency that supplies the aged care facilities it is inspecting.

Publicly available data presented by submitters reveals that labour hire ultimately costs more than deploying inhouse capabilities, due to margins and “ticket clipping” by the contractor. But the workers themselves are paid less than public servants. Insecure work arrangements can cause serious problems, as seen with aged care workers deployed by agencies to multiple facilities at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers do not receive leave or benefits, resulting in declining efficiency.

The government is investing a lot of money into “a resource that is lost at the end of the contract”, wrote Professionals Australia. “[S]ignificant investment is made in staff who then leave for more secure jobs”, wrote the CPSU. Double handling, increased errors, declining customer satisfaction and trust or reputational damage often result. APS staff are wasting time training “a steady stream of new labour hire workers due to high turnovers, on top of their usual workloads”, according to CPSU member feedback. But the benefit of that investment ultimately goes to the private company engaging those workers. Public money is diverted on a large scale to for-profit companies, many of which pay little to no tax. Carving out the most difficult work for consultants “does not build skills for the future” within the public service; “[I]nstitutional knowledge has been lost”, CPSU members reported. There are gaps in training. Long-term capability and quality service delivery for Australians is being compromised.

External consultants

Gauged by population, Australia spends more than any other nation in the world on consulting! Our consulting industry (private and public) is the fourth largest in the world. The federal government spent almost $1.2 billion in one year with eight private consulting firms “in an entirely unaccountable way”, according to the report. At the start of financial year 2021 the government was set for a record spend on consultants, tracking at more than $2 million per day!

The CPSU reports “a tacit preference for privatised advice”. Of concern is the tendency of private advisers providing “the advice you want rather than the advice that perhaps should be given”, said CPSU National Secretary Melissa Donnelly. Further, consulting firms are likely to provide policy advice that leads to more outsourcing.

In addition to abolishing the ASL cap the committee report rightly recommends putting a cap on consultancies, rather than APS roles. Outsourcing should be a rare exception and when used, require full tracking of data and full transparency.

The blowback against outsourcing in the UK has been so withering, especially since the collapse of multinational contractor Carillion which dominated government work contracts, that a shift back to fostering adequate capacity within the public sector has been initiated. In May 2021, the Government Consulting Hub (GCH) was launched, aimed at upskilling the Civil Service and reducing reliance on external consultants. In an Australian version, such a proposed agency would be responsible for assessing and approving all requests for use of external consultants. The Jobs and Skills Exchange of the Victorian Public Service, established in July 2019 as an online platform providing access to a pool of talent internal to the public service, is also cited by the report as a potential model. Note that over the last two years, the federal government had no choice but to “temporarily” recruit thousands of additional public sector workers to work with the National COVID-19 Coordination Commission, Services Australia, the Tax Office or Department of Health.

Bipartisan consensus on cuts

Liberal Opposition Leader Tony Abbott had spelled out in 2010 a Coalition target of slashing 12,000 public service positions by not replacing retirees for two years, saving $4 billion. But Labour Treasurer Wayne Swan’s 2013-14 budget, four months before Abbott was elected, included unpublicised reductions in public service staffing by 14,500 jobs. The new Liberal government slashed a further 2,000 jobs in the first Abbott government budget, bringing the total to 16,500. In his 13 May 2014 budget appropriations speech, Treasurer Joe Hockey declared: “A smaller, less interfering government won’t need as many public servants.” This was the infamous budget after which Hockey and Finance Minister Mathias Cormann were photographed celebrating by smoking cigars.

The Average Staffing Level (ASL) cap was formally ushered in with the 2015-16 budget, aimed at permanently reducing the number of public servants to 2006-07 levels.

In December 2013, after his election as PM, Abbott had convened a National Commission of Audit, which recommended new benchmarks to limit pension increases and tighten eligibility requirements; a slower roll-out schedule for the National Disability Insurance Scheme; healthcare reform to make health services “more efficient and competitive”, and “policy interventions aimed at restraining expenditure”; “rationalising and streamlining government bodies”; and “Reform and restructure of the Australian Public Service”.

A Finance Ministry statement in response to the Audit declared that government spending was on an unsustainable trajectory, proposing an all-round gutting of government functions at all levels, including reduction in the number of boards, committees and councils; “consolidation” of various services, from border protection to healthcare; new privatisations and additional outsourcing; increased competitive tendering and procurement; and various public sector “efficiency” measures.

As documented in “Outsourcing government is a corporate takeover” (AAS, 23 Sept. 2020), this Audit was one of a series of Royal Commissions, Commissions of Audits and Budget Reviews conducted since the mid-1970s which recommended a barrage of economic reforms, dictated by the Australian think tanks associated with the British neoliberal Mont Pelerin Society, that savaged government capabilities and funnelled money into private coffers.

The governing Coalition has already made clear it will stick with the reform process, but will the Labor Party really have the guts to bust up the bipartisan economic consensus if they depart the safety of the Opposition benches?

Public servants face burnout, demoralisation; vets impacted

The following anecdotes from public service employees and union representatives were cited in submissions to the inquiry or summarised in the final report.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs: There are some areas in DVA that require a bit of training. It’s demoralising to see months of training leave with a contractor, because they have gone somewhere else for a permanent position or a longer contract….

National Disability Insurance Agency: I have trained eight people in the last 18 months who have all left before they were skilled enough to be useful. We still don’t have these positions filled and are about to do it all again. I am facing burnout due to the increased workload and the extra work of training staff who ultimately do not contribute to the team.

NDIA: We have had entire teams made entirely of contractors quit and all that skill and knowledge is lost in an instant. I have had to pick up the work of three additional people with no notice, these positions (still going to labour hire) have not been filled almost 12 months later, four labour hire [workers] coming and going in the meantime.

The CPSU also cited feedback from members in the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission warning that the agency’s “long-term regulatory capability” was not being retained as contracted staff, many of whom had developed good skills, either did not last their full contract term or were “head-hunted” into permanent positions by aged care providers.

Ms Fiona Duffy, Workplace Delegate, CPSU: …we’re constantly training and losing people and training and losing people. Because we can’t offer them any security and people are leaving, we’re spending a huge amount of time and resources training people, and it actually has a negative impact on productivity. … It takes six to 12 months for a [veterans] claims delegate to learn the [three pieces of complex] legislation, and we lose about a quarter of all labour hire in the first six months anyway. We’re constantly fighting to keep staff. The good staff move off to permanent jobs, so it doesn’t really have the impact on the backlog that you would hope. Just throwing more labour hire at it isn’t necessarily going to get through the claims because of the cost on the ground of having to manage a large cohort of labour hire in the claims space.

The CPSU submitted that the excessively high caseloads and lack of staff contributed to delays in claims processing, which led to frustration and anxiety for veterans. … a “direct line” could be drawn between the use of labour hire by DVA and increased waiting times and reduced services for veterans. … The CPSU referenced the poor mental health facing many veterans in Australia as reported in the media, and pointed to research commissioned by DVA showing that delays to processing compensation claims directly impacted the mental health of claimants. … The CPSU stated that two thirds of the staff working in CCS [Coordinated Client Support] were employed on short term labour hire contracts. It emphasised that CCS provides assistance to “the most vulnerable and complex cases”, and due to high staff turnover, veterans must constantly re-tell their story to a new case manager, at the risk of exacerbating their trauma.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 2 February 2022