The extraordinary cover-up of the Sterling First rent-for-life scandal reaches to the highest levels of government. The dubious involvement of the regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), its lies to parliament and inexplicable protection of Sterling’s predatory schemers raises serious questions—what is really going on behind the Sterling scandal? A Senate inquiry into ASIC and the Sterling Group is urgently needed to expose this sophisticated whitecollar crime operation involving the government, the banks, a Big Four auditor, experienced Ponzi scheme artists, and ASIC.

Sterling schemers go way back

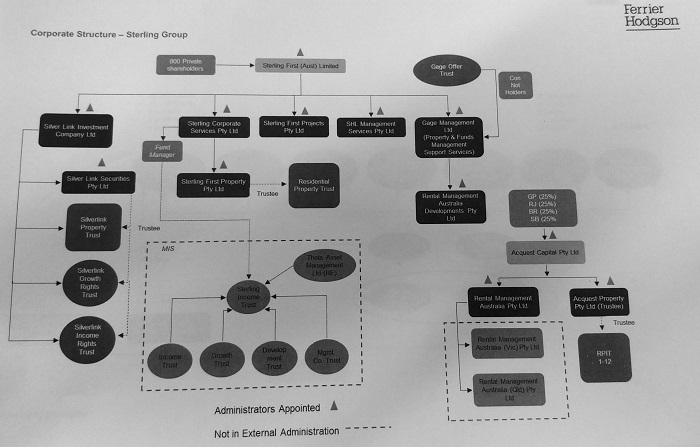

The ringleaders of the Sterling First scandal are experienced Ponzi schemers and appear to have friends in high places. Ray Jones, founder of Sterling First, is a former bankrupt and has been a key figure in financial scandals such as the 1990s Rural Property Trust (RPT). A central character in Jones’s scheme was Ken Court, brother and son of former Western Australian Premiers Richard and Charles Court. Financial mogul Kerry Packer held a one-time controlling interest in Ascot, the parent company of Jones’s RPT. The Australian Securities Commission (later ASIC) quietly dropped charges against Jones and other RPT directors in 1995, claiming there was not a realistic prospect of conviction.

Another Sterling director was Simon Bell, a key figure in the disastrous Westpoint property development Ponzi scheme. Big Four global accounting firm KPMG, appointed by ASIC to audit Sterling, came under fire for its role as Westpoint’s auditor and its former association with a Westpoint director. Advocate for Sterling victims and founder of the Banking and Finance Consumers Support Association, Denise Brailey, warned ASIC about Westpoint in 2001, but the regulator’s inaction permitted the scheme to continue until it collapsed in 2006 with total losses of $680 million. The Sterling First collapse can be traced back to the Westpoint disaster, as the instigators were all known to each other. Simon Bell and other Westpoint directors served alongside key Sterling personnel, including founder Ray Jones, as directors of Western Australia’s Settlers retirement villages during the period of 1998-2012.

ASIC’s protection racket

Sterling’s directors, including Jones and Bell, were well known to ASIC because of their involvement in Westpoint and numerous other financial Ponzi schemes which included a fake bank and failed property development projects.

In 2010, Bell and Jones set up Heritage, an investment company which raised $15 million from 600 investors by falsely claiming it was going to be listed on the ASX. Brailey reports that although ASIC was aware Heritage had fleeced millions in its fake share scandal, the regulator permitted the company to change its name to Sterling in 2013.

Brailey reports that in 2014-15, ASIC’s lawyers were assisting Sterling’s directors to rewrite their defective “Product Disclosure Statements” (PDS), legally required documents disclosing risks to investors, as they breached numerous corporate laws. In parliamentary hearings, ASIC commissioners would later claim that they had believed Sterling was outside their purview, because they thought it was a real estate business model. However, ASIC’s earlier assistance to Sterling directors proves that when the Group’s rent-for-life scheme was initiated in 2015, ASIC was well aware it was a financial product and under ASIC’s regulatory jurisdiction.

Brailey has evidentiary documentation proving ASIC was also aware that the Sterling Group’s scheme enticed elderly retirees to sell their homes and use their life savings to pay forty years’ rent in advance. In 2015, ASIC contacted WA Consumer Protection (CP) to notify them that Sterling’s original 99-year lifetime leases were illegal under state law, and asked CP to ensure Sterling corrected the oversight by splitting up the leases into five-year lots. ASIC’s handy compliance tip-off enabled Sterling directors to keep their scheme going.

Brailey reports WA Consumer Protection continued to communicate their concerns about Sterling to ASIC, including an invitation to join CP in observing a Sterling seminar in December 2016, which ASIC refused.

Despite their evident knowledge to the contrary, ASIC continues to insist that Sterling First victims were not tenants, but investors. ASIC commissioners have lied in parliamentary hearings, claiming that they first became concerned about Sterling’s activities when alerted by the Western Australian Department of Commerce in March 2017.

ASIC waited until August 2017 to issue a stop order on Sterling’s products. However, the regulator just looked on as Sterling side-stepped the order and continued to sign up retirees under a different company name. A further $11 million was taken from retirees in the period after ASIC’s stop order until Sterling’s collapse in May 2019.

Sterling victims have been given the run-around by regulators and the government. As revealed in a 19 March 2021 parliamentary hearing, ASIC had insisted that Sterling victims should go to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) for help. However, a court case later revealed that it is legally outside of AFCA’s jurisdiction to investigate these complaints. Moreover, the government had not provided AFCA with any funding to even investigate complaints! Brailey reports that Sterling victims have been cruelly misled by the government’s promises of an eventual compensation scheme, which has dragged on for two years. On 16 July 2021, Treasury released draft legislation for the muchpromised Compensation Scheme of Last Resort, but Sterling victims do not fall within its scope.

Sterling scandal is far-reaching

The Sterling scandal is far-reaching and goes beyond the rent-for-life scheme. Financial professionals such as mortgage brokers, settlement agents, property consultants and financial advisors were involved in every step of drawing unsuspecting landlords into buying a Sterling investment property. There are indications of coordination between Sterling ringleaders and all the major banks in a mortgage debt scandal. Financial engineering designed by Sterling director and actuary, Simon Bell, convinced landlords to pay the banks’ inflated values for their investment properties. (AAS, 14 July 2021.)

In addition, there are serious questions over the role of KPMG. ASIC gave KPMG $440,000 to investigate the directors of Sterling, despite the fact that KPMG and Sterling director Simon Bell were both involved in the Westpoint Ponzi scheme. KPMG has still not produced a report or interviewed a single landlord or tenant.

In August 2018, ASIC sent door knockers around to Sterling tenants, asking them if everything was alright with their rental agreement. One was an ASIC lawyer/investigator who went to work for KPMG several months later. Brailey reports that curiously, KPMG has not permitted Sterling’s tenants or landlords to be deemed creditors.

When Sterling collapsed in May 2019, an administrator from Ferrier Hodgson was appointed, named Martin Bruce Jones. Shortly afterward, KPMG swooped in and acquired Ferrier Hodgson, appointing themselves Sterling’s liquidators. Curiously, Martin Jones has been appointed administrator for numerous companies which KPMG advised or audited prior to their collapse. This includes Great Southern, a massive agri-investment scheme, for which KPMG had provided an “independent expert” nod of approval only a few months before its catastrophic collapse. Martin Jones was also the administrator for Westpoint, and was recently holding creditor meetings for Westpoint subsidiaries at the same time as acting as Sterling’s administrator.

Macquarie Bank’s involvement

The Sterling Group had a convoluted business model involving not only the rent-for-life scheme, but also property development, investment and management. ASIC has confirmed that the Sterling Group “pioneered” the concept of a long-term residential lease “coupled with the business model of property investment involving the aggregation of rent rolls.” As well as operating the Sterling rent-for-life scheme, the Group had acquired a rental property management or “rent roll” business, which grew to 3,500 properties at its peak.

Sterling directors boasted to their staff that it was a certainty that their rent roll would eventually encompass a third of all rental properties in Australia. Brailey observes that the ambitious project would have required politically-connected backers, and would have been highly lucrative if it had succeeded. Notably, the well-known financial alchemists at Macquarie Bank had been the Group’s lender from 2014, which gave Macquarie a first ranking security over all present and future rent rolls. One of Sterling’s ringleaders, Robert Marie, was a former state manager for Macquarie and managed the bank’s Cash Management Trust.

After Sterling’s collapse, Macquarie Bank, as the Group’s secured creditor, sold the valuable rent roll at a bargain price to Yolk Property Group in November 2019. Several weeks prior to the sale, Yolk established a new property investment arm which offers mezzanine finance products, a type of investment which was key in the Westpoint Ponzi scheme. Sterling ringleader Robert Marie was also a key player in a fractional property investment scheme which is still operating, BrickX. BrickX was founded at the same time as Sterling, reportedly “worked closely with ASIC” to launch its product, and also involves mortgages financed by Macquarie.

Rent-for-life scheme brought to you by the government

Brailey reports the Sterling rent-for-life scheme was the first of its kind in Australia. Sterling insiders reported the ringleaders claimed to have an “in” with Treasury, boasting that they were the “only” ones who would be allowed to run the scheme in Australia.

According to Brailey, the rent-for-life scheme originated in the United States, and was allowed into Australia by Joe Hockey towards the end of his term as Treasurer. The scheme had ruined many retirees in the USA, and Brailey says “they knew what they were letting in”.

Hockey was then appointed Australia’s ambassador to the USA, where he helped to drum up business for Macquarie Bank, spruiking it as a “flag-bearer” in international markets and inviting its CEO and top managers to prestigious events, including the Washington state dinner for Scott Morrison in 2019. In May 2020, several months after resigning his ambassadorship, Hockey was appointed the Macquarie Group’s US frontman.

Scott Morrison succeeded Hockey as Treasurer in September 2015. As Treasurer, Morrison had regular meetings with ASIC, where he was briefed on upcoming and concerning issues. According to Denise Brailey, this would have included the Sterling Group’s activities pioneering a controversial financial scheme, particularly as the directors were well known to ASIC. As Treasurer, Morrison, who was formerly of the Property Council of Australia and worked briefly at KPMG, is therefore responsible for allowing the scheme to continue.

After his August 2018 appointment as Prime Minister, Morrison was succeeded as Treasurer by Josh Frydenberg. Frydenberg presided over the supposed wind-up of the Sterling Income Trust in August 2018, when the company continued spruiking Sterling products using different entities and company names until its May 2019 collapse.

Not only did Frydenberg fail to protect consumers from Sterling’s financial predators, he has continued to ignore hundreds of letters from elderly Sterling tenants who have been fleeced of their life savings and face imminent eviction from their homes.

This is unsurprising, as Frydenberg and Morrison serve the corrupt financial system and not the Australian public. When former ASIC Chair James Shipton and Deputy Chair Daniel Crennan attempted to follow the recommendations of the Financial Services Royal Commission by litigating against the banks, Frydenberg instigated a contrived expenses scandal which threw them out of office, although both were cleared of wrongdoing.

The catastrophic collapse of Sterling, which fleeced the life savings of vulnerable pensioners, is a predictable outcome of deliberate government policy. The Morrison government has determined that financial dealings must be governed under the principle of caveat emptor—Latin for “let the buyer beware”— because neoliberal politicians like Morrison and Frydenberg don’t believe in regulation. ASIC is supposed to be operationally independent, but it takes policy direction from the government. Decades of “buyer beware” policies have resulted in a weak and ineffective financial regulator which has been captured by the banks. The Australian public pays dearly for these “buyer beware” policies, while the regulator and government protect predatory scammers and the corrupt banks.

The Citizens Party has documented Frydenberg’s sweeping structural changes at ASIC, which have furthered hobbled the regulator. Frydenberg replaced Shipton with a former lawyer for scandal-wracked Deutsche Bank, Joe Longo, whom the 3 June 2021 Australian Financial Review called “the ‘business-friendly’ regulator craved by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg”.

The Sterling scandal is being hushed up at all levels of government. Shortly after Sterling’s collapse, Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Housing Michael Sukkar said he believed there were “red flags” about ASIC’s regulatory inaction and promised to act on any findings, but has evidently been silenced—there has been no further comment since. Assistant Defence Minister Andrew Hastie refuses to help his Sterling constituents, who have reported that Hastie “hides” from them. On 9 July 2019, over one hundred Sterling tenants gathered at then-Finance Minister Senator Mathias Cormann’s office to report the crime to him. They asked Cormann to take the elevator down from the top floor to meet with them, but Cormann called the Australian Federal Police on the pensioners!

The Sterling cover-up goes all the way up to Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who, as Treasurer, was responsible for ASIC permitting Sterling’s predatory rent-for-life scheme to fleece elderly pensioners of their life savings. We must expose the rot at the core of the financial system and reveal the true cost of the government’s “buyer beware” policies— Australians must urgently demand a Senate inquiry into ASIC and the Sterling Group!

KPMG’s dubious track record

The 18 February 2020 AFR reported that a parliamentary grilling from Greens Senator Peter Whish-Wilson had revealed that Big Four auditing company KPMG failed to raise concerns about companies it audited shortly prior to their collapse. KPMG had also been the subject of extensive litigation for its audit quality and advice given to collapsed companies, but denied that the level of litigation was a metric for its audit quality, instead suggesting that litigation funders and class action law firms were to blame. Conveniently for KPMG, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg recently introduced controversial legislation which has made it difficult, if not impossible, for non-profit organisations to bring class actions. (AAS, 7 July 2021.)

When the Sterling Group collapsed in May 2019, an administrator from Ferrier Hodgson was appointed, named Martin Jones. Shortly afterward, KPMG swooped in and acquired the company, appointing themselves Sterling’s liquidators. Curiously, Jones has been appointed administrator for numerous companies which KPMG advised or audited prior to their collapse. This includes Forge, Mirabela Nickel, Arrium, Gunns, Allco, and Great Southern, a massive agri-investment scheme for which KPMG had provided an “independent expert” nod of approval only a few months before its catastrophic collapse. Martin Jones was also the administrator for Westpoint, a catastrophic property Ponzi scheme which involved Sterling Director Simon Bell, and KPMG as Westpoint’s auditor. Martin Jones, now of KPMG after Ferrier’s acquisition, was recently holding creditor meetings for Westpoint subsidiaries at the same time as acting as Sterling’s administrator. Ferrier Hodgson has audited numerous companies which KPMG advised or audited prior to their collapse, some of which have been the subject of legal action against KPMG, including Nylex, CP1, Equititrust and Octaviar.

By Melissa Harrison, Australian Alert Service, 21 July 2021