As Australian and New Zealand banks prepare for the seemingly inevitable introduction of central bank negative interest rates, Sweden—the first nation to implement negative rates at a central bank level following the global financial crisis—is labelling the experiment a failure.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) kept its rate at 0.25 per cent at its monthly meeting on 2 June, but a number of economists had made a last-minute push for a move into the negative domain. Westpac chief economist Bill Evans told the Sydney Morning Herald that the RBA board should consider going into negative territory. If the economy “is deteriorating even more than is currently expected”, negative rates would become thinkable, allowing banks to cut lending rates and enabling households and borrowers to take cheap loans, along with improving the “competitiveness of the currency”, i.e. currency devaluation. These so-called benefits have been refuted by the Swedish experience.

Chief economist at RBC Capital, Su-Lin Ong, suggested that a new pandemic wave or some other shock would likely force the move into the negative rate domain. The RBA continues to insist it is “extraordinarily unlikely” but will not rule it out.

Sweden

An 8 May article by Lund University economists Fredrik Andersson and Lars Jonung, titled “Don’t do it again! The Swedish experience with negative central bank rates in 2015- 2019”, published by the Centre for Economic Policy Research, concluded that the policy did not have a substantial impact on reviving inflation, which was its main aim, and in fact increased financial vulnerabilities.

The academics documented that: an increase in inflation was more closely correlated with the shifting European business cycle than with central bank interest rates; the Swedish currency depreciated by 20 per cent under the negative rate regime, impoverishing households; property prices rose by close to 50 per cent in relation to disposable income (over 2012-16) and efforts to counter this resulted in increased economic inequality; and household debt reached record levels.

The authors suggest that had negative rates been avoided, the central bank (Riksbank) “would have faced a better-balanced economy today, better balanced in the sense of less asset price inflation, less financial imbalances, and more room for the Riksbank to react to the next downturn.”

The costs of negative rates outweighed the benefits, the authors wrote. “In our opinion, the clear message from the Swedish experience of negative policy rates is: ‘don’t do it again’.”

Some Australian economists seem to be paying attention. As reported by the Australian Financial Review on 1 June, HSBC economist Paul Bloxham said the RBA was conscious of the damaging economic impacts of negative rates, and MLC senior economist Bob Cunneen reckoned the failure of negative rate policy overseas gave it a “very low chance” of being adopted here.

New Zealand

The Reserve Bank of NZ (RBNZ) is reportedly in discussion with NZ banks to prepare them operationally for negative rates at some point in the future, due to the building economic crisis. A survey of 3,000 New Zealanders reported by Stuff News on 27 May revealed that the majority of NZ households are in financial crisis or on the brink; one in ten households have missed a mortgage or rent payment.

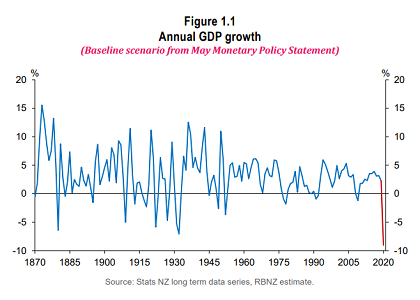

The RBNZ’s Financial Stability Report for May 2020 states that NZ, which had a very strict lockdown to combat the coronavirus, has suffered “an unprecedented decline in economic activity”; even taking an expected recovery into account, it now faces the largest projected decline in annual GDP in at least 160 years, bringing with it “financial distress for a significant number of households and businesses” (graph). Under severe scenarios, such as a second virus wave and lockdown, “the viability of banks would come into question”. Gaming out the NZ Treasury’s third-worst economic scenario saw “unemployment rising to nearly 18 per cent and house prices falling by almost half”. Under this scenario, “banks would fall below minimum capital requirements” and would “have to undertake significant recovery responses such as raising new capital from shareholders to avoid resolution options”, said RBNZ. (Emphasis added.) “Resolution” refers to New Zealand’s overt bail-in regime, which allows the regulator to confiscate deposits and junior bonds to recapitalise a collapsing bank. RBNZ is currently conducting a review of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1989 which includes “in-principle decisions” to enhance and clarify the crisis resolution framework, and insure $50,000 worth of deposits for each depositor, per institution. This demands closer scrutiny.

Negative rates and banning cash

Throughout the European Union, negative interest rates have wiped out small banks and eroded the savings of large or new account holders. The IMF has made clear that for negative rates to function as an effective arm of monetary policy, restrictions on cash are required to prevent people and businesses using it to avoid being taxed via their bank account. Though famously a near-cashless society, Sweden does not have statutory cash restrictions; but 17 EU nations do, with limits ranging from €500 to €15,000.

Former IMF economist Kenneth Rogoff, who is outspoken on the “need” to phase out cash to make negative interest rates work, reiterated the importance of negative interest rates in a 17 April paper, “Negative interest rate policy in the post COVID-19 world”, in which he declared: “By far the biggest obstacle is to forestall wholesale cash hoarding”. This objective, however, is “becoming politically easier over time as cash is marginalised”, adding that it is plausible that “COVID-19 will lead to a sharp reduction of cash use even in the last bastion of small transactions”.

The “heroic central bank response to the recent pandemic” has not obviated the need for interest rate policy, he said, lamenting the fact that “no country yet has taken the simple but necessary steps to prevent wholesale cash hoarding by financial firms, insurance companies, and pension funds, necessary for ‘whatever it takes’ deep negative rate policy to be effective.”

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 3 June 2020