The combined government-Reserve Bank financial package in response to coronavirus is $320 billion (one third of which is a blatant bank bailout). This is an eyewatering sum of money, especially as total Commonwealth government debt is $571 billion, which is around 30 per cent of gross domestic product. Imagine if in this crisis, or even before coronavirus, a politician proposed to spend $300 billion on a single infrastructure project. What political leader would be game to hang their reputation on a project of such enormous cost?

For instance, there are presently two major infrastructure projects under discussion in Australia, both with widespread support and opposition. They are the Bradfield Scheme to divert North Queensland floodwaters to inland Queensland and down into the Murray-Darling Basin; and the high-speed train from Melbourne to Brisbane through Canberra and Sydney. The Bradfield Scheme is supported by Bob Katter’s party, One Nation, the Citizens Party, a new party called the Bradfield Party, and has significant support in the National Party, including from the leader of Queensland’s LNP, and even the support of former Queensland Labor premier Peter Beattie. Its main opponents are environmentalists who don’t want “nature” touched in any way, and neoliberals who oppose public investment in infrastructure, insisting that only privately-funded projects are legitimate.

The Melbourne to Brisbane fast train is supported by people in all parties, including the Greens, and federal Labor leader Anthony Albanese has championed the concept as a nation-building project to revive the economy from its current crisis. Its main opponents are the neoliberals in the major parties.

Both projects would be very expensive. The full Bradfield Scheme is a very large project. First proposed in the 1930s by Dr J.J.C. Bradfield, the engineer who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Bradfield Scheme has gone through multiple feasibility studies over the years, the most recent by the Queensland government in 1984. That study estimated the cost would be $2.49 billion, but in 2020 dollars 36 years later it would be much more. The Bradfield Party estimates its version of the scheme would be $15-$17 billion; critics have insisted that it would have to be much more than that.

As for the Melbourne-Brisbane fast train, the last feasibility study conducted by the Gillard government in 2013 assessed it would cost $114 billion, making it nominally the most expensive infrastructure project in Australian history.

How could we justify such expensive projects at this time of economic depression and spiralling government debt?

As it happens, the Melbourne-Brisbane fast train would actually not be the most expensive infrastructure project in Australian history, not even close. We once did build the equivalent of a $300 billion project—the Snowy Mountains Scheme. And we did it at a time when Australia had the greatest level of government debt in its history.

At the end of WWII, Australia’s Commonwealth government debt was 120 per cent of GDP. Today’s 30 per cent government debt to GDP pales into insignificance in comparison. In 1949, Prime Minister Ben Chifley launched the Snowy Mountains Scheme as the centrepiece of his government’s vision for postwar economic development, to “win the peace” just as Australia had won the war. Opposition leader Robert Menzies, who opposed the project, didn’t bother to attend the launch. Chifley had legislated that the Snowy Mountain Scheme should be funded with national credit from the Commonwealth Bank, but because he lost the election later that year, Menzies put a stop to funding it through national credit, and insisted on funding it out of the government budget, from which funds were provided to the Snowy Mountains Authority as a loan.

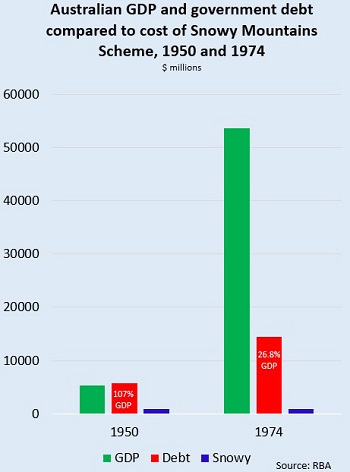

At the time, the government estimated the project would cost the equivalent of $820 million. In 1950, this was an enormous sum of money. According to Reserve Bank statistics, Australia’s GDP in 1950 was the equivalent of $5,301 million, and Commonwealth government debt was $5,694 million, or still 107 per cent of GDP. The $820 million price tag for the Snowy scheme was a whopping 15 per cent of GDP! Today 15 per cent of GDP would be a $300 billion project.

Did Australia’s political leaders choke on this cost, and not proceed? While Menzies likely would have, Chifley thought big, and by the time Menzies took office the scheme had become very popular, so he soon recognised he should get on board. Amazingly by today’s standards, and to sceptics of government projects, the Snowy scheme was completed in 1975 on time and on budget—$820 million. By then, the investment in the Snowy scheme and the economic growth it helped to drive, including through immigration growth, had transformed Australia. As the graph shows, the economy had grown ten-fold in nominal terms (not completely accurate as it doesn’t factor in inflation, but enough to illustrate the point), government debt was nominally greater but had fallen to 26.8 per cent of GDP, and the cost of the Snowy was then 1.5 per cent of GDP.

In deciding on policies to get Australia out of its current economic and unemployment crisis, infrastructure projects should not be looked at purely as costs, but as investments in growing the economy and national wealth. That’s how political giants of the past built the Australia we enjoy today, and that’s how we’ll turn this crisis into an opportunity to create prosperity for future generations.

By Robert Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 13 May 2020