The government is preparing to introduce legislation in the last week of November to fulfill the recommendations of the RBA Review, according to Treasurer Jim Chalmers (box). If not stopped, that legislation will elevate unelected bankers at the Reserve Bank above the elected government when it comes to the nation’s finances.

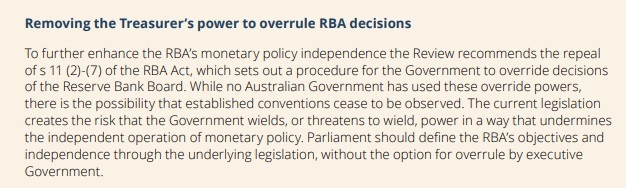

The number one reform demanded by the RBA Review is removal of the government’s power to override decisions of the Reserve Bank. Its recommendations were handed down in March. Treasurer Jim Chalmers declared in a 20 April press conference: “We intend to introduce legislation to reinforce the independence of the RBA by removing the government’s right to veto its decisions; we intend to introduce legislation to strengthen the RBA’s mandate”. Since July, Chalmers has been consulting with the opposition on adopting those recommendations, including by changing the legislation which governs the RBA.

The extensive changes to the RBA governing legislation, which the Review wants enacted by July 2024, require bipartisan support. The RBA Review panel itself specified that if bipartisan support were not forthcoming, the government should decline to take the legislative pathway, in order not to jeopardise the full suite of changes. In that case, the Review panel suggested a non-legislative pathway to informally clarify proposed changes in a new Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy—the compact between government and RBA—“including a statement that the Government will not use its overrule power and the RBA will not use its power to determine the lending policy of banks”.

But if the Leader of the Opposition is anything to go by, it looks like bipartisan support is in the bag. Peter Dutton gushed over the need to protect the RBA’s independence on 13 July: “The Reserve Bank governor has the independence because they need to make tough calls in our country’s interest, even if they’re unpopular calls”, the Opposition Leader said. “We don’t want somebody there who’s been involved in the political process at a senior level, and I think that’s a very important point to make, and we’ve made that clear to the government as well.”

The Australian reported on 14 July 2023: “Dr Chalmers will also be seeking bipartisan support for amendment of the Reserve Bank Act in line with the Review’s call for repeal of the power of government to override decisions of the RBA.”

“This power detracts from the independent operation of monetary policy and the credibility of the monetary framework”, it said.

The Australian restated that the Review called for the policy agreement between government and RBA, the Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy, to be refreshed— notwithstanding the numerous revisions made since it was first composed in 1996. The last Statement was signed by Treasurer Scott Morrison and past RBA chair Philip Lowe in 2016. In a 12 July speech Dr Lowe said he expected a new statement to be finalised before the end of the year. Chalmers said the new statement would “reaffirm the government’s commitment to the independence of the Reserve Bank and support for the inflation targeting framework”. This Statement will be the back door for recommended changes if legislation proves difficult.

Carney protégé leads the Review

Two months after winning government, Treasurer Jim Chalmers in July 2022 initiated the RBA Review panel. Its remit was to assess the RBA’s objectives, particularly its “inflation targeting framework”, its policy tools, as well as its governance, culture and financial infrastructure. Fighting inflation has come to indicate a commitment to enacting austerity, a code which covers a range of policies that gouge ordinary people to subsidise the collapsing financial system.1 The RBA Review was also empowered to examine increased coordination of monetary and fiscal policy, something for which Lowe has recently been pushing, also as a means to prop up the existing financial system. (“Rethinking the financial matrix: two pathways”, AAS, 20 Sept.)

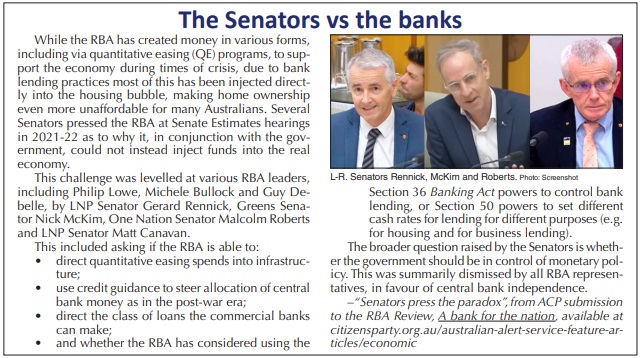

The real purpose of the Review, however, was to block the push by several Senators from various parties, to compel the government to use the RBA for the benefit of the nation by directing its quantitative easing and other monetary injections into desperately needed infrastructure, and guiding the interest rate and lending policies of commercial banks to prevent financial bubbles. (See “Senators press the paradox”, subsection of ACP submission to RBA Review, “A bank for the nation”.)

The RBA Review was led by Canadian economist Professor Carolyn A. Wilkins. Wilkins was the former Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada (2014- 20) for all but a year of the Governorship of Mark Carney (2013-20), but from late 2013 was Advisor to the Governor. Carney has been the central figure, from his top jobs at the Bank of Canada, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)-run Financial Stability Board (FSB) and Bank of England, in engineering monetary regime change, by: signing nations up to the post-2008 “bail-in” policy, which steals people’s money to save banks; and pushing for central banks to direct the fiscal (budget) policy of governments as well as monetary policy decisions.

Earlier Wilkins led a financial derivatives unit at the Canadian central bank and was Managing Director of the bank’s Financial Stability Department in 2011-13, at the same time Carney was heading the Financial Stability Board at the BIS. Wilkins oversaw the Bank of Canada’s COVID quantitative easing program. She is currently an external member of the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee, which is committed to protecting “financial stability”, code for protecting private banks at any cost (i.e. at the cost of the average family), and represented Canada at the FSB, both at the Plenary and Standing Committee on Assessment of Vulnerabilities. She represented Canada on the BIS’s Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and co-chaired the BCBS Working Group on Liquidity. Canada was cited as a model for the RBA Review panel to judge the RBA against, along with the BoE.

The panel also included Professor Renée Fry-McKibbin, a leading Australian economist, primarily employed in university roles, and Dr Gordon de Brouwer, who has held senior Australian public service roles including at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Treasury and RBA.

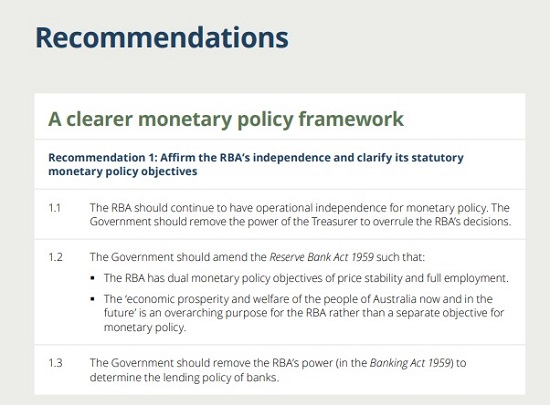

What the Review recommended

The first point alone of the RBA Review recommendations, seen in the image at right, would strip any government oversight of the RBA as well as any RBA control over the private, commercial banks. It would strengthen the RBA’s independence to act free from the interference of elected authorities and remove the mandate that the bank act in the interests of the “economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia”, designating it instead an “overarching purpose”. Making it an “objective” “provides too much discretion to the RBA”, stated the Review panel. The RBA’s objectives, as stated in the RBA Act, should be simply a dual mandate of achieving price stability and full employment.

Apart from addressing governance and transparency issues, all of which are aimed at ensuring greater independence from government and deference to external expert advice, the Review also recommends a legislative mandate for the RBA to protect “financial stability” and proposes to reinforce cooperation between various agencies that promote financial stability.

The battle for power over private banking

The powers which the RBA Review is recommending for removal are a relic of the era prior to financial deregulation. The Australian Citizens Party stated in its report on the RBA Review immediately after release: as the Review admits, those “hangover” powers have never been used2, but indications that they might be utilised under crisis conditions by a government responding to necessity and popular demand, was enough: The task of the RBA Review was to pre-emptively crush those powers.3

These powers stemmed from fights during the Great Depression, between the Labor government which wanted to expand credit to build the economy and the government-owned Commonwealth Bank, which prevented new credit issues under the pretext of smothering inflation, at the instruction of the Bank of England.

Commonwealth Bank Governor Sir Robert Gibson thus defied the government, blocking the credit required for economic recovery, but the matter was so controversial that a banking royal commission was convened to determine whether the government or the central bank had the final say on matters of finance.

In its final report the 1937 Royal Commission on Banking declared that “The Federal Parliament is ultimately responsible for monetary policy, and the Government of the day is the Executive of the Parliament.” It recommended that if conflicts arose between the government and the board of the bank, the government should assure the board it accepts full responsibility for the decision but “it is the duty of the bank to … carry out the policy of the government.”

The recommendation was not adopted by the government of the day, but when John Curtin and Ben Chifley4 came to power in 1941, they immediately used their war-time powers to deploy the Commonwealth Bank to lend directly to the government for the war effort which included mobilisation of the economy. Curtin and Chifley embedded the recommendations of the royal commission in the 1945 Commonwealth Bank Act, which remained in the successor legislation, the 1959 Reserve Bank Act, in the clause that empowers the Treasurer to override the decisions of the bank which Chalmers now intends to remove.

A refresher on RBA powers

A review of the unused powers that remain in law today, makes crystal clear why the RBA Review wants to rewrite the legislation underpinning the Australian banking system.

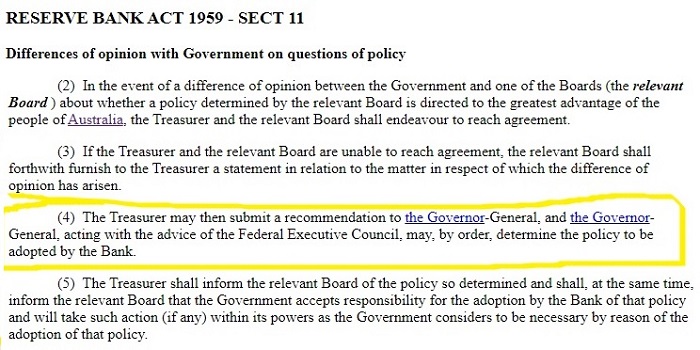

Section 11, RBA Act 1959: Gives the government the ultimate power over monetary and banking policy. It states that under dispute resolution processes the Treasurer can make the call via the Governor General:

This is also set out in the Statements on the Conduct of Monetary Policy from 1996 to 2010 (the language disappears thereafter), which state that Section 11 of the Act “allow[s] the Government to determine policy in the event of a material difference”, however it adds, “the procedures are politically demanding and their nature reinforces the Bank’s independence in the conduct of monetary policy”.

Section 36, Banking Act 1959: Gives the RBA the power to direct lending (advances) into specific areas of the economy.

Section 50, Banking Act 1959: Another clause in the Banking Act allows the Reserve Bank to exercise control of interest rates.

By a combination of these powers it is still possible for the government to direct credit into the economy to revive our infrastructure, industry and agriculture. The government can dictate to the RBA, and the RBA can dictate to the private banks—acting to channel credit into productive pursuits utilising bespoke lending and interest rate policies by economic sector. The international banking mafia led by the BIS that currently has Australia under its boot will not tolerate such a move towards sovereignty; but it has not yet won this fight!

Footnotes:

Even experienced neoliberals warn against prescriptions of RBA Review

Even prominent Australian veterans of the neoliberal government and banking reforms of the 1980s and 1990s have condemned the arch-neoliberal changes to Australian banking legislation proposed by the RBA Review as “risky”, “radical” and “uncertain”.

Former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating warned that the Australian government must be able to overrule the RBA if necessary, telling the ABC on 28 April: “Political power, its management and employment in office, must, in a working democracy, take precedence over any subordinate bureaucratic structure.” He insisted that the legislation to remove the government’s override power must not be waved through parliament; some democratic check on its power must remain in place.

Former Liberal Treasurer Peter Costello said there was “no reason to leap into a new system that is untested and uncertain”. The nation’s longest-serving treasurer warned the changes could result in “less focus and less accountability from the RBA in the area where it really should be held responsible”. He argued that if the proposed changes had been in place during 2020-22 it would not have “helped the bank avoid the mistakes” that were made.

Similarly, former RBA Governor (1996-2006) Ian Macfarlane warned the authority of the governor, including over interest rate decisions, would be diminished by the rise of external members positioned on a new Monetary Policy Board. He described the Review’s proposals as “radical changes” and an “untried experiment” which would shift the balance of power away from the governor “to six part-timers we know little or nothing about”.

Macfarlane was scathing about disappearing democratic processes. The Australian reported: “Mr Macfarlane said it was ‘inexcusable’ that the federal government had agreed to implement all the recommendations of the review panel on the day its report was released, without any public discussions.” He noted that “Treasury officials wrote the report for the review panel. ... It was as though Canberra has decided (and) the rest of the country has to accept it. The rest of the country only got to see it after it had been signed, sealed and delivered in Canberra.”

Former prime minister John Howard backed Macfarlane’s assessment according to the Australian: “I do agree with Mr Macfarlane very strongly. He was an excellent RBA governor.”

In March, ahead of the release of the RBA Review report, another former RBA chief (1989-96), Bernie Fraser, noted that changes in government policy, ranging from housing policy to taxation, had undermined the RBA’s ability to rein in inflation. Noting neoliberalism as a factor, he warned that increased independence from government could lead to less independence from the dictates of financial markets.

Economist Ross Garnaut likewise put RBA difficulties in the context of changed economic structures, making clear that changes to the RBA alone would not solve the problems faced. In a 3 May speech, he pointed out that an over-reliance on monetary policy to manage inflation had actually worsened inflation by driving up rents and other costs.

Senior Lowy Institute fellow and past RBA board member (2011-16) John Edwards warned that the changing RBA leadership composition represented a shift to an “expert board rather than an advisory board of the kind we have now”, calling for more debate on the Review’s recommendations.

Other leading economists have warned that the RBA risked “losing control of the cash rate” under the RBA review panel’s “radical” proposal to have voting external experts outnumber central bank officials on a new board that will set the country’s monetary policy, according to The Australian on 29 May.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 15 November 2023

Supporting material is available at our Australian Alert Service - feature articles - economic page, including:

RBA Review submission – Australian Citizens Party

Read the Citizens Party's submission to the RBA Review (PDF)

Supporting material: