The sacking of Australian Labor Party Prime Minister Edward Gough Whitlam on 11 November 1975 by Governor-General Sir John Kerr is for good reason regarded by many Australian patriots as the death-knell for the nation’s pretensions to democracy and sovereignty. The final decision to dismiss him undoubtedly lay with Queen Elizabeth II, without whose imprimatur no vice-regent, let alone as notoriously insecure a lickspittle as Kerr, would have dared risk such a momentous act. What ultimately decided the Crown upon such drastic action, however, remains a matter of conjecture. As the Australian Alert Service has reported, the Whitlam government’s “buy back the farm” campaign to wrest Australia’s vast mineral and energy wealth back from foreign, mainly US- and British-owned corporations1 was itself a sufficient threat to Anglo-American imperial interests that the Crown and its agents had been prepared for months to remove him by decree, should more conventional means fail.2 In a series of articles published 8-12 November in the online journal Pearls and Irritations, however, former Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet division head Jon Stanford makes a convincing case that the final decision to do so was triggered by Whitlam’s policy, first announced in 1974, that for Australia to attain independence in foreign policy it required that all foreign military and intelligence personnel and installations be removed from its soil. This was to start with the supposedly “joint” but entirely US-controlled signals intelligence base at Pine Gap in the Northern Territory, the lease on which was to expire in December 1975. For reasons which Whitlam himself appears not to have fully understood—principally because senior Australian officials conspired to keep Pine Gap’s true functions and capabilities secret from him—this would have been such a strategic and geopolitical disaster for the USA and Britain that its prospect would undoubtedly have united those countries’ governments, and more importantly their intelligence establishments, in a determination to remove Whitlam from government by any means necessary, whatever the cost.

When the ALP under Whitlam won government in December 1972, it included “a significant [left-wing] faction that had little sympathy for the American alliance and was hostile to the presence of US bases on Australian soil”, Stanford wrote. “Although Whitlam himself was by no means anti-American, he opposed Australia’s military involvement in Indochina [Southeast Asia] that had ‘placed the American alliance firmly in the context of a foolish and futile war’. While still supporting the ANZUS [Australia-New Zealand-United States] alliance, he sought to develop a more independent foreign policy with less of a Cold War focus.” But “Having announced the withdrawal of the last Australian troops from Vietnam”, wrote Stanford, “the Prime Minister’s first major foray into foreign affairs had unfortunate consequences.” Like many other world leaders, Whitlam wrote officially to US President Richard Nixon “criticising intense American bombing raids on North Vietnam at Christmas 1972. However, his proposal to engage with other countries in a call to both the US and North Vietnam to return to the conference table caused Nixon to take ‘great offence’ and enraged Henry Kissinger”, Nixon’s National Security Advisor and later (and from 22 Sept. 1973 to 3 Nov. 1975, concurrently) Secretary of State, who “branded it as ‘being put by an ally on the same level as our enemy’. Consequently, Nixon characterised Whitlam as a ‘peacenik’ and placed Australia on his ‘shit list’ of countries, ranked number two behind Sweden.”

The build-up

Soon thereafter, the Nixon Administration began making what look like preparations to roll Whitlam should he continue to make a nuisance of himself—starting, in July 1973, with the appointment of Kissinger confidante Marshall Green as US Ambassador to Australia. Stanford describes Green merely as a “very senior official in the State Department” and an “accomplished career foreign service officer”, whose appointment “reflected … the Administration’s concerns” about Whitlam’s policy direction. Renowned Australian journalist John Pilger, writing 23 October 2014 in the Guardian, more aptly described Green as “an imperious, sinister figure who worked in the shadows of America’s ‘deep state’. Known as ‘the coup-master’, he had played a central role in the 1965 coup against President Sukarno in Indonesia—which cost up to a million lives.” He was also involved in the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) -backed coups in South Korea in 1961, and Cambodia in 1970. Green, Stanford wrote, “went to Canberra with a clear agenda. In a meeting with Kissinger in July 1973, he stated that the first priority in his mission in Australia was ‘preserving our defence installations’.”

Whitlam was “philosophically opposed to hosting foreign bases”, wrote Stanford, but “he was willing to accept the American facilities on the grounds of Realpolitik so long as the Australian government was fully apprised of their purpose. He was justifiably concerned they could be instrumental in launching a nuclear attack and thereby may cause Australia to become a nuclear target. As soon as he took office, Whitlam was briefed on the US facilities by Sir Arthur Tange, Secretary of the Defence department. While Tange emphasised the need for complete secrecy over the facilities, he was economical with the truth as to their true purpose. Most importantly, he neglected to tell Whitlam that the Pine Gap facility supported a massive CIA espionage operation over which Australia neither had any control nor access to the intelligence the facility produced. For nearly three years, the Prime Minister continued to believe that Pine Gap was a communications facility operated by the Pentagon in liaison with Australia’s Defence department, and that it monitored compliance with the strategic arms limitation agreements.” (Emphasis added.)

When he eventually learned the truth about Pine Gap in September-November 1975, Whitlam was furious, and the decision to shut it down was cemented. The Nixon Administration, however, had been on high alert since April the previous year, when “just before the May election and with no warning to the Americans, Whitlam announced a radically different position” to that he had heretofore espoused: “‘that there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour extensions or prolongation of any of those existing ones.’ With the Pine Gap lease due to expire in December 1975, Whitlam’s statement caused reverberations in Washington. Green told Alan Renouf, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, that it ‘represent-ed a grave threat to the global western balance against the Soviet Union, and ANZUS would be called into question’.”

In July 1974, Nixon via Kissinger ordered that a top-secret National Security Study Memorandum (NSSM) be prepared on US policy toward Australia. “Our traditional close friendship with Australia has been under pressure for several years”, the study concluded, “because of Australia’s desire for greater independence in foreign affairs and because of Prime Minister Whitlam’s style.” (Emphasis added.) Stanford cites analysis published in 2005 by Stephen Stockwell, a professor of journalism at Griffith University, which shows that following a multi-agency meeting convened by Kissinger to discuss the NSSM, in August 1974 primary jurisdiction over the US relationship with Australia was transferred from the State Department, to National Security Council (NSC) at the White House. Notes Stanford: “if his objective was to destabilise the Whitlam government, Kissinger would have more options available at the NSC, including involving the CIA.”

The CIA would not, of course, be alone. Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), or MI6 as it is better known, was also actively working against Whitlam, in collaboration with its American counterpart.

Enter the spooks

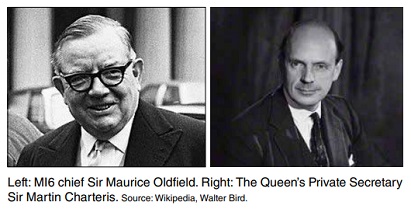

Presuming the NSC did decide upon covert action against the Whitlam government, Stanford asserts, “there is no question that [MI6 chief] Maurice Oldfield would have been fully informed and, indeed, consulted. There is no way that the Americans would have undertaken covert action in a significant Commonwealth country, particularly a member of Five Eyes, without involving the British.” For reasons outlined at the beginning of this article, the implicit assumption that Britain acted against Whitlam only at America’s behest is flawed; but otherwise, Stanford’s logic is sound—not least because the British are never ones to turn down an opportunity to have someone else do their dirty work. Or as Stanford puts it, “Oldfield would not have wanted to break protocols by running a MI6 operation in Australia or involving ASIS [the Australian Secret Intelligence Service] against its own government. It could also cause problems with his own political masters from the British Labour party. … [He] would be more likely to leave the ‘spooky fiddling’ to the CIA, while cautioning them not to get caught.” In all its 114 years of existence, MI6 has never declassified a single document, record or item of correspondence, not that either it or the CIA would be likely to keep records of their operations against an allied country’s government in any case. What is a matter of public record, as Stanford notes, is that “top secret signals traffic between MI6 and ASIS increased by 74 per cent in 1975” (emphasis added).

It also happened that one of Oldfield’s top contacts in Australia was Justice Robert Hope—the man Whitlam had appointed in August 1974 to head the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security. “According to Oldfield’s biographer (and nephew), Martin Pearce”, wrote Stanford, “Oldfield communicated frequently with Hope and even had his home telephone number. Eventually this persistence paid off when Hope advised Oldfield that [Whitlam] was encouraging the Royal Commission to recommend a significant reduction, if not cessation, of the ties between the Australian security agencies and their American and British counterparts.” Whitlam had already ordered domestic intelligence agency the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) to cease cooperation with the CIA the previous month. “This was a red flag”, wrote Stanford, “and Oldfield saw it as a threat to Pine Gap and the other facilities. He informed [CIA Director] Bill Colby immediately. Noting the closeness of this relationship between the agencies, Pearce states ‘what united MI6 and the CIA in particular was their concern that Whitlam might close down the joint satellite tracking station at Pine Gap near Alice Springs. … [And] as it was Whitlam who’d been driving the matter, in the view of the intelligence agencies something needed to be done’.” (Stanford’s emphasis.)

And thus we return to the role of the Crown—which, as Stanford puts it, “has a long history of a close connection to the covert world. … Although members of the civil service, MI6 officers were officially classified as Crown servants, and they took the distinction seriously.” As if to reinforce how laughable is the notion, lapped up by naïve monarchists (and, it must be said, by Whitlam himself, who insisted to his dying day that the queen had nothing to do with his sacking), that the king or queen is a mere figurehead and “above politics”, Stanford reports: “For over 70 years, Queen Elizabeth took a keen interest in intelligence matters. Even before she became Queen, with the support of her new assistant private secretary, Colonel Martin Charteris, she began receiving classified material. Charteris’ previous job had been in British military intelligence in Jerusalem, where he had worked closely with an owlish, clever young Major called Maurice Oldfield. … Following Whitlam’s statement in Parliament in April 1974, the Queen’s red [intelligence dispatch] boxes would have contained an analysis of his intention not to renew the leases on the US facilities and the implications for the strategic balance.” Having been promoted to Private Secretary in 1972, it was Charteris whose correspondence with Kerr on the queen’s behalf—the infamous “Palace Letters”—proved upon their public release in 2020 that she had indeed been an active participant in the plot to sack Whitlam.3

Still, as Stanford points out, “While Oldfield and Charteris would have discussed the possibility of Whitlam’s dismissal, it would not have been the preferred option unless absolutely necessary. … If he were to be forced out due to covert action and then won an election on an anti-foreign bases ticket, it would be a disaster. If he found out the Crown was involved as well, it would be the worst of all worlds.” And as Stanford reports, Ambassador Green, in a February 1975 discussion with US Defence Secretary James Schlesinger, had opined that notwithstanding Whitlam’s statement in Parliament the previous April, the US bases in Australia seemed secure provided the CIA’s operations at Pine Gap remained secret. But “If Whitlam should discover the truth about Pine Gap, all bets were off. In the first week of November that is exactly what happened, and the Prime Minister was on a rampage. Now he had to go.”

Footnotes:

By Richard Bardon, Australian Alert Service, 22 November 2023