In the escalating drive to transfer power from elected governments to independent agencies, new legislation is headed for a vote in the Australian Parliament to consolidate International Monetary Fund (IMF)/Bank for International Settlements (BIS) directives to sacrifice citizens to save the banking system. If approved, the bill will hand greater power to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), allowing them to join the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) in taking drastic action in the event of a new financial crisis.

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Financial Market Infrastructure and Other Measures) Bill 2024 follows similar legislation, including the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018, a.k.a. the “bail-in” law, and proposed amendments to laws governing the RBA, the Treasury Laws Amendment (Reserve Bank Reforms) Bill 2023.

The bail-in law gave emergency powers to APRA, which allow global banking authorities to dictate the confiscation of Australians’ savings and investments to avert a banking meltdown. The attempted RBA amendments are aimed at removing the government’s control over the RBA for the same purpose, but the legislation has stalled after a Senate inquiry raised outrage.

The new bill concerns financial infrastructure which could rupture during a financial crisis. In particular, it addresses a weakness introduced in the effort to prop up the financial system after the 2007-08 global financial crisis, in the form of Central Counterparties (CCPs) which provide post-trade clearing and settlement of speculative financial transactions in order to manage counterparty risk centrally.

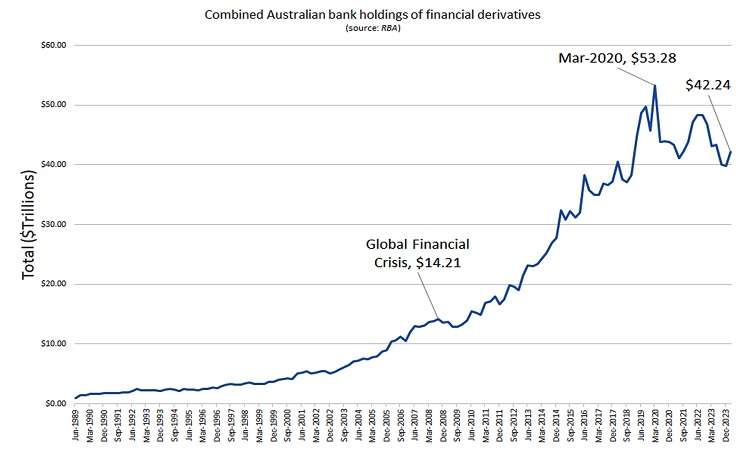

Rather than regulators actually regulating the multi-quadrillion dollar global derivatives bubble, they devised new too-big-to-fail institutions. The BIS soon admitted that these middlemen in speculative financial trades had become “systemic players” that could cause “a destabilising feedback loop, amplifying stress”, as indeed occurred in the March 2020 market crunch. (“CCP scheme can crash the entire banking system”, AAS, 27 May 2020.)

Recommended by regulators

It was the regulators who proposed this redistribution of power—to themselves. The new bill to rescue CCPs and related market infrastructure is the result of recommendations made in 2020 by the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR), the coordinating body for Australia’s main financial regulatory agencies, which comprises APRA, ASIC, the Australian Treasury and the RBA, which chairs the Council.

A leading factor in the CFR’s analysis was the derivatives trade. In the first paragraph of its introduction, the CFR report noted that “FMIs [Financial Market Infrastructures] in Australia support transactions in securities with a total annual value of $18 trillion and derivatives with a total annual notional value of $185 trillion. A disruption to the orderly provision of FMI services could cause a disruption to the wider financial system, which may have large economic costs.” The figures cited are the notional value of derivatives trades for the year to 31 December 2019. “These markets turn over value equivalent to Australia’s annual GDP every three business days”, the report revealed.

The CFR admits that its proposal cues off the international agenda led by the IMF and BIS, which gives bankers the final say during a financial crisis. This is the only way to guarantee that the collapsing global financial system survives, the concern being that politicians who are answerable to voters could stand in the way of drastic measures to save the system.

The report stated: “The resolution regime put forward by the CFR in this recommendation is designed to be consistent with the Key Attributes wherever appropriate to the Australian environment.” The 2013 “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes”, produced by the BIS’s Financial Stability Board, first laid out the global push for bail-in regimes, whereby the savings and investments of citizens would be absorbed by banks to recapitalise themselves and remain solvent, so as not to threaten the “system” as a whole. (“Resolution” means restructuring a troubled financial entity without recourse to bankruptcy or liquidation, to ensure continuity of its “systemically important” functions.)

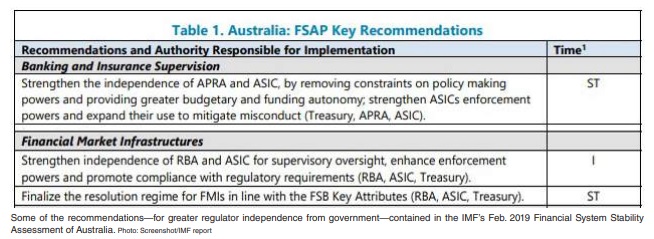

After the Australian Parliament passed bail-in laws to resolve banks in 2018 with just eight Senators present, the IMF told Australia to get with the program of financial market infrastructure reform. In various of its 2019 reports the IMF declared finalisation of a resolution framework for FMIs “a priority”.

The CFR lambasted “current arrangements, where the Minister has responsibility for a number of operational decisions” as “inconsistent with this approach [separation of responsibilities between the Government and regulators] and out of step with comparable international regimes”. It recommended the transfer of powers relating to clearing and settlement facilities to the RBA and ASIC. Regulators “need strong and dependable powers to carry out their mandates and mitigate the risk of disruption to FMI services”, especially “with the current heightened global risk environment”, it insisted.

What’s in the FMI bill?

While the bank bail-in power went to APRA, the new bill implements the CFR recommendations by creating a new “crisis management and resolution regime” for market infrastructure run by ASIC and the RBA. (It will not be lost on the politically aware that a parliamentary inquiry into ASIC has just reported that ASIC already has too wide a field of responsibility which it cannot manage—see ACP media release 10 July.)

Just as APRA can do with a bank per bail-in laws, the new legislation will allow the RBA to intervene to save a clearing and settlement (CS) facility, our equivalent of a CCP, that has failed or is at risk of failing and may thus threaten the stability of the financial system.

The resolution powers allow the RBA to take control of a distressed entity in order to resolve it, appoint new management or shift its activities to a third party, and issue directions to it. During the resolution period stays can be put on contractual rights and moratoria on enforcement or litigation actions. Actions to recapitalise the entity can be taken or its functions transferred to another entity.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum for the new bill, recapitalisation involves: issuing, cancelling or selling shares, or rights to acquire shares; reducing share capital by cancelling any paid-up share capital not represented by available assets; and varying or cancelling rights or restrictions attached to shares in a class of shares in the body corporate.

“Compulsory transfer of shares and business is an important tool in the package of resolution options available to the RBA”, it states. “This power enables the RBA to transfer a failing or insolvent CS facility to a solvent body corporate to continue providing critical CS services.” This could include forming a bridge institution to migrate functions of the entity.

The legislation also provides crisis prevention powers. “The RBA will have a suite of increased general powers that may be used at any time” to prevent a financial crisis, the Explanatory Memorandum states.

RBA and ASIC regulatory powers will also be enhanced:

- Certain supervisory and licensing powers for market facilities previously controlled by the Minister will be transferred to ASIC, or the RBA. These include actions such as issuing directions and suspending or cancelling licences. There are 51 licenced market operators in Australia which are supervised for licensing and conduct. The RBA oversees the systemic risk aspect of their operation.

- ASIC can make emergency rules without consent of the minister or consultation with the RBA, or the public, regarding FMI entities, to protect the financial system.

- The threshold for ministerial approval for acquiring interests in financial market bodies is raised from 15 to 20 per cent. The ASX, which was in its own category where ownership greater than 15 per cent could be permitted by regulation, will be aligned with other market bodies in this respect. Under the new system, ASIC can approve voting power of more than 20 per cent of non-market bodies such as a clearing and settlement facility or derivative trade repository.

- There are also provisions whereby local regulators can assist in international operations to limit systemic risk.

Also in the RBA’s “crisis resolution toolkit” is a facility whereby the Treasurer can appropriate up to $5 billion (per event) for actions to maintain a CS facility during a crisis, if recovery and resolution tools are insufficient alone. This is “intended to be a last resort option”, says the Explanatory Memorandum, but this provision is not subject to disallowance (i.e. being overruled) by the parliament.

The Explanatory Memorandum includes several appendices in the form of papers justifying the bill’s proposals. Among them are earlier IMF reports demanding greater independence for APRA and ASIC and completion of the bail-in regime. A 2019 IMF technical note points to a 2015 government report pushing for the FMI resolution regime, indicating the long-term project this legislation reflects— yet another example of the commitment to the bipartisan economic consensus both parties are wedded to. The original resolution blueprint, the oft-cited FSB “Key Attributes”, proposed the resolution regime in 2011, thirteen years ago! An excerpt of the final report of the 2014 Financial System Inquiry, conducted by former Commonwealth Bank boss David Murray, reminds us also of the commitment by both sides to resist actual solutions, or anything encroaching in that direction: “The Inquiry does not recommend pursuing industry-wide structural reforms such as ring-fencing. … Neither APRA nor the RBA nor the banking industry saw a strong case for these reforms.” Indeed.

Ring-fencing is a Claytons version of the 1933 US GlassSteagall banking separation law, which banned deposit-taking banks from using speculative instruments such as derivatives. Only by domiciling commercial banks with deposits safely outside the domain of speculation, can the most important financial infrastructure be protected from a new financial meltdown. The period from Glass-Steagall’s inception to its takedown in 1999, during which there were no major banking crises, is testimony to the fact that it’s a regulatory framework that actually works.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 10 July 2024

For more on bail-in, see our "Stop 'bail-in'" campaign page.