Across the nation, businesses, farms and the hospitality sector are crying out for staff while nearly 790,000 Australians are unemployed (according to official figures which vastly underestimate the true labour force underutilisation).

The lack of international students, backpackers, and incoming skilled migrants is revealing long-term structural weaknesses in our economy, with hundreds of thousands of jobs that cannot be filled. A few days into Victoria’s fourth pandemic lockdown on 28 May, Council of Small Business Australia CEO Peter Strong told Sky News that a lot of business were already looking at closing because they can’t find staff. In fact, across the entire country businesses are reducing opening hours for lack of workers. With no competition for jobs, it is the best time to be an unskilled worker in Australia, said Strong. “There are around 600,000 fewer people in Australia than pre-COVID and around 227,000 of those people had the right to work”, chief executive of national industry association Restaurant and Catering Australia Wes Lambert told SBS on 22 May.

We have jobs and we have workers—all that is required is organisation. Contrary to the typical laissez-faire non-action, a hands-on approach is called for. As, for example, when Christine Holgate became CEO of Australia Post. Before even starting the job, she conducted extensive field research around the globe, quickly determining that the future of postal services lay in their widespread retail network—an indispensable advantage for banking. After consulting with every level of the company, from executives to licensed post office providers, posties and unions, she rolled up her sleeves and got her hands dirty, negotiating with banks and politicians to pull off the Bank@Post deal which saved the post office from declining profitability, and therefore the threat of privatisation. That was just a stepping-stone to the goal of transformation to a full postal bank. Where there was an obstacle, Holgate found a way around it; when superiors told her it wasn’t possible, she made it happen.

Unfortunately, when external consultants are deployed to do a job, there is invariably a different outcome. The performance of Australia’s unemployment services, privatised in the late 1990s, provides yet another polemic against outsourcing. The Guardian on 28 May reported on a review of the Disability Employment Services sector by Boston Consulting Group (as yet unpublished—surprise!) which revealed recent reforms had increased the revenue of providers but not the chances of employment. “Providers told the review they spent 40-50 per cent on administrative tasks such as monitoring jobseekers’ compliance with their job search”, reported the paper.

Peter Strong, who once worked as an employment counsellor for the Commonwealth Employment Services (CES), decried the failure of ideology-driven changes to employment services, which “created some millionaires ... on the back of the long-term unemployed”, and called for a new version of the CES. A solution requires that “politicians and policy makers will have to confront the real world not the textbook world”, he demanded, ending with “a message for laissez-faire economists: you are a bunch of shallow intellects who have failed all of us due to your lazy pomposity: end message.”

Examples from history—including the World War II period and China’s successful emergence from poverty in the last forty years—show the level of commitment and organisation required to get the nation back to work.

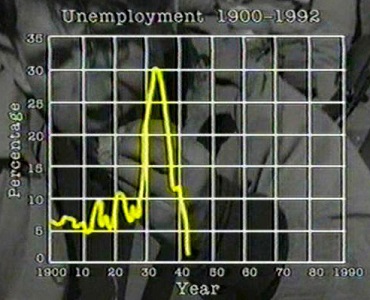

With the advent of WWII an expansion of government credit to fund the war effort saw unemployment disappear within months (graph). The credit fuelled a huge expansion of manufacturing, turning what had been our single greatest weakness into an economy-boosting strength.

A key part of the economic turnaround was putting an innovator in charge. In 1939, BHP General Manager Essington Lewis was given the post of Director-General of Munitions. Dubbed “industrial dictator”, he took charge of building adequate national defences, from planes to ships, arms and ammunition, with all the steel, manufactures and machines tools required for the process. While fully embracing the extraordinary powers provided him, he emphasised that bureaucrats like him were the servants of the toolmakers, fitters and munitions workers. Although it was argued that some of the envisioned projects were beyond the skills of Australians—four of every five workers engaged in aircraft production had no industrial experience— Lewis carried it off. His effort built upon the work of A. E. Leighton and the Munitions Supply Laboratories, set up in 1922, which began to develop the industrial and scientific capacities required. (“How Essington Lewis pulled off an industrial miracle”, AAS, 25 Mar. 2020; “Lessons of the Munitions Supply Board (1921-39)”, AAS, 13 May 2020.)

This tradition was alive more recently. Commenting on the final report of the Aged Care Royal Commission in March, National Seniors Australia Chief Advocate Ian Henschke discussed the transformation of education and healthcare during the 1970s baby boom, which included rapid training programs for teachers and nurses, much of which was “on-the-job”. He proposed 6-month training courses in cities and large regional centres to ready thousands more aged care workers. But you can’t leave it to the market, he told Sky News—government must play a role: “Market forces have got us to where we are today”, he declared. (There are many other factors, which can all be solved, such as ensuring decent, growing wages and incentives to relocate people to where the work is.)

After the onset of the Great Depression, US President Franklin Roosevelt oversaw a tailored approach to getting people back on their feet. Nearly a third of the nation was ill-housed or homeless by 1932; a year later half of all mortgages were in default. In addition to drastic reform of the banking system and massive public infrastructure programs, FDR created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. Not only did it refinance existing mortgages at lower rates and flexible terms, and provide additional cash loans, its agents personally visited all clients to help them find work, reorganise finances, access public assistance or even locate foster children. (“Lessons From FDR’s Handling of the Housing Crisis”, Executive Intelligence Review, 6 Apr. 2007.)

Bearing striking similarity to this program is China’s ongoing Targeted Poverty Alleviation scheme, which assigns a member of its taskforce to every family in targeted provinces. Participants are personally assisted with training courses and finding a job, starting a local business or engaging in a local initiative. A vital component is the massive investment in infrastructure opening new job opportunities and connecting remote regions with markets and services. Expansion of free education, promotion of classical and traditional Chinese culture and accessible health care are also critical components of the program.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 2 June 2021