Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 1)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

If the reader has heard of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China, it is likely through lurid news media headlines about the alleged abuse and enslavement of the area’s Uyghur ethnic inhabitants. In this issue of the Australian Alert Service, we begin a new series of articles, aimed at demystifying what is going on in and around Xinjiang, and why.

This first article in the series briefly sketches the history of the region of which Xinjiang is part, and its position as the westernmost frontier area of modern China. Its place within China and astride the New Silk Road makes Xinjiang a target for Anglo-American strategists eager to destabilise China and wreck Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. Subsequent articles will explore the history of “geopolitical” manoeuvring around Xinjiang, from the British Imperial “Great Game” in the 19th century, through the Anglo-American “Arc of Crisis” policy against the Soviet Union during the late Cold War, and up to the present. We will show that human rights concerns have been weaponised against China by outside intelligence agencies who care little for the population living in Xinjiang, but are using the age-old imperial techniques of fomenting ethnic and religious conflicts, separatism and terrorism to disrupt the society of a presumed adversary nation.

On the southern side of the Eurasian landmass, about halfway across it from West to East, the Indian tectonic plate of Earth’s crust is gradually moving northward, subducting under the Eurasian plate. Over the past 40 or 50 million years, this collision has thrust up what are now the highest mountain ranges on Earth: the long arc of the Himalayas, reaching from far northeast India, westward to Afghanistan; west and northwest of the Himalayas are the Karakoram Range in China, India and Pakistan, Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush, and the Pamirs centred in Tajikistan; and extending eastward from the Pamirs is the Tian Shan Range (Chinese: Mountains of Heaven), in Kyrgyzstan and western China. Between these towering mountain ranges are a few fertile valleys and several high plateaus, some of which are steppe (unforested

grassland) and others large deserts.

These mountains and plateaus have been called High Asia, or the Roof of the World. Located there are small Himalayan countries like Bhutan and Nepal, Afghanistan, three of the four nations of Central Asia proper (former Soviet republics Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and part of Uzbekistan), parts of India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Russia and Mongolia, and two provinces of China—Tibet, and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Xinjiang is bisected east-west by the Tian Shan mountains, with the steppe area to their north called Dzungaria or “Northern Xinjiang”, while to the south are the Tarim River Basin and the 337,000 km2 Taklamakan Desert.

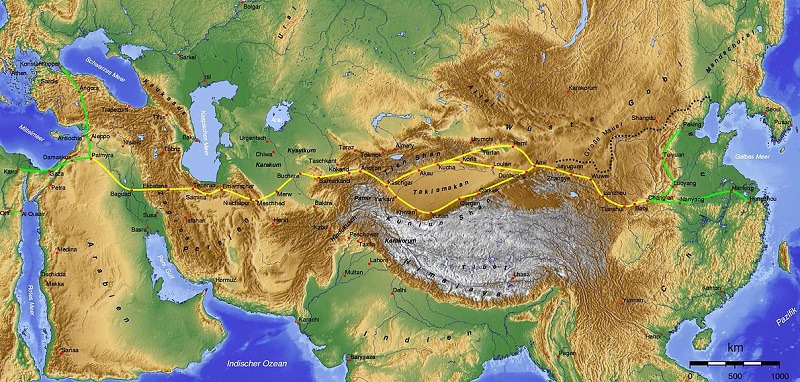

Though sparsely populated, this region has played an important role in the economic and cultural history of the planet, as well as being fiercely contested by major powers—Eurasian ones, and outsiders like Britain and the USA—over the most recent several centuries. The ancient Silk Road trade routes between China and Europe skirted the Taklamakan Desert along both its northern and southern edges.

Xinjiang, like adjacent Central Asia, has been populated by various peoples over the ages. Two thousand years ago an ancient Indo-European people called the Tocharians, their language akin to many Indian subcontinent and European tongues, developed agriculture around oases in the Taklamakan Desert. For a thousand years, various nomadic tribes, larger powers based in Mongolia, and Chinese dynasties successively controlled parts of the area. Around AD 1000, Turkic peoples professing Islam moved in, and dominated until the Mongol Empire, having conquered China, began to rampage westward across Eurasia in the 13th century. (As a forerunner of international imperial meddling in central Eurasia, the financier-run city-state of Venice, ancestor of the City of London and Wall Street, provided banking, a slave market, and intelligence services for the Mongol Khans.) In 1209 a small state centred near modern Urumqi in northern

Xinjiang and ruled by ethnic Uyghurs, a Turkic people, swore allegiance to the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan.

In 1759, with the Qing Dynasty’s conquest of the Dzungar Khanate, a remnant of the Mongol Empire, the area became a lasting part of China and was named “Xinjiang”, meaning approximately “new borderland”.

The Great Game and Mackinder’s ‘Heartland’

As the Qing Dynasty weakened in the 19th century, including under the pressure of Britain’s Opium Wars against China, it experienced various uprisings. In Xinjiang, the clashes were not only between the Chinese central government and Turkic ethnic groups, but also among the latter. The Dungan Revolt of 1862-77, for example, was led by Yaqub Beg from the Khanate of Kokand in modern Uzbekistan; establishing a breakaway state around Kashgar (Kashi) at the western end of the Taklamakan Desert, he had some Xinjiang Uyghurs in his army, while other Uyghurs allied with the Qing and fought against him. Clashes between different Muslim Sufi brotherhoods were another factor in the uprising. The British and Ottoman Empires both recognised Yaqub Beg’s regime and sent their intelligence liaisons to him.

In the 19th-early 20th-century period, another strategic confrontation on the Roof of the World came into play, between the British and Russian empires. Britain was forever trying to expand its control over the continent from its staging ground in India, while British strategists were always fearful about real or imagined Russian designs on India, the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire. The struggle between England and Russia to dominate this strategically important and resource-rich region became known as the “Great Game”.1

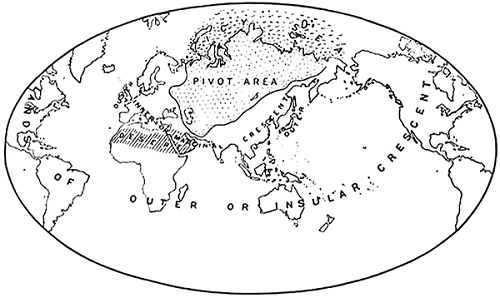

In 1904 Halford Mackinder, the British geographer and father of so-called “geopolitics”, presented The Geographical Pivot of History to the British Royal Geographical Society. He proclaimed Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Russia to be the “pivot area” of world geopolitics, also calling it the “Eurasian Heartland”. Mackinder declared that whoever controlled the Heartland would command the world.

Mackinder’s Heartland theory was highly influential on successive geopoliticians, including American national security advisors in the Cold War like Henry Kissinger (under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford in 1969-75), the man who later said he had “kept the British Foreign Office better informed and more closely engaged than I did the American State Department”, and Zbigniew Brzezinski (1977-81 under President Jimmy Carter).

Brzezinski was a Polish-American geostrategist, diplomat, and co-founder of the Trilateral Commission international policy group. As Carter’s advisor, he escalated US hostility towards the Soviet Union, including covert Central Intelligence Agency funding and arming of Afghan mujaheddin (anti-Soviet militants). In 1978 he called for stepped-up American activity along an “Arc of Crisis” on the Soviet Union’s southern perimeter. Academic allies of Brzezinski churned out books on the potential of Turkic and other Islamic insurgencies to slash up the “soft underbelly of the Soviet Union”; The Islamic Threat to the Soviet State, for example, appeared in 1983 from Sorbonne Prof. Alexandre Bennigsen, one of Brzezinski’s mentors.

Kissinger, in his 1994 book Diplomacy, insisted that the USA remain focussed on Eurasia even after the Cold War had ended, warning in a mixture of Mackinder’s doctrine and the 19th-century European “balance of power” politics he himself adores: “Geopolitically, America is an Island off the shore of a large landmass of Eurasia, where resources and population far exceed the United States. The domination by a single power of either of Eurasia’s two principle spheres—Europe or Asia—remains a good definition of strategic danger to America…. For such a grouping would have the capability to outstrip America economically, and the end, militarily.”

In The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (1997), Brzezinski wrote that after 500 years as the centre of world power, Eurasia was still “the chessboard on which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played…. It is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges, capable of dominating Eurasia and thus also of challenging America.”

On the centenary of Mackinder’s influential paper, British historian Paul Kennedy wrote in the Guardian (19 June 2004) that Soviet domination of the “Heartland” during the Cold War had revived Mackinder’s theories. Now, he added, “with hundreds of thousands of US troops in the Eurasian rimlands and with an administration [of President George W. Bush] constantly explaining why it has to stay the course, it looks as if Washington is taking seriously Mackinder’s injunction to ensure control of ‘the geographical pivot of history’.”

From Silk Road to Land-Bridge

The ancient Silk Road network of trade routes connected China and the Far East with Europe and the Middle East, starting around 130 BC when China found a link to the Mediterranean Sea via the Fergana Valley in the Pamir Mountains. The caravan routes would develop and fall out of use repeatedly, with the succession of empires at both ends, always traversing vast expanses of difficult terrain. They facilitated world-altering exchanges of art, religion, science and language.

In the 19th century, a major reason for the Great Game and Mackinder’s geopolitical doctrine was that American economists and their followers in Russia and elsewhere had begun infrastructure-building projects to revive and modernise these ancient trade routes. If railways were built across Eurasia, that modern, fast means of transport would challenge “Britannia Rules the Seas”—Britain’s supremacy in international trade as a maritime “Rimland” power, in geopolitical terms.

Henry C. Carey, economic advisor to American President Abraham Lincoln, promoted such railway construction. Lincoln himself had advocated economic opportunity for all citizens, government-funded infrastructure projects, protection for industry and family farmers, and the first American Transcontinental Railroad (completed in 1869, four years after his assassination). Carey and his circle of American nationalists championed cooperation among sovereign nations on ambitious infrastructure projects, driving the transformation of other countries into powerful industrial nation-states which could improve the lives of their citizens. He envisioned world-wide electrification, industrialisation of Russia and China with thousands of railway lines, and Germany becoming a superpower and America’s partner in world development. Carey denounced British imperialism, in particular Britain’s policy of destroying China with opium and Britain’s “work of annihilation”—the occupation and devastation of India.

Carey’s circle directly influenced policy-making in Russia, then led by Lincoln’s Civil War ally Tsar Alexander II. A Carey ally proposed to secure the Tsar’s support for a Russian-American joint project to construct a railway from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean.2 By participating in international railway projects, Russia itself would be strengthened and unified.

Alexander II was assassinated in 1881, but Finance Minister Count Sergei Witte, a student of the American System of productive credit,3 got the Trans-Siberian Railway built in 1891-1916, with a spur into northeastern China added in 1897-1902 under a concession from the Qing government of Imperial China. These projects, together with German plans for the Berlin-to-Baghdad Railway, were Mackinder’s nightmare. They helped motivate Britain to instigate provocations and diplomatic manoeuvres, leading to World War I.

But the genie of Eurasian economic development was out of the bottle, and it inspired the best thinkers in China, as well.

The father of modern China, Sun Yat-sen, studied in America in his youth and was inspired by Abraham Lincoln’s practical political and economic policies. Dr Sun’s 1924 book Three Principles of the People was inspired not only by Confucian teachings, but also by the concept of “government of the people, by the people, for the people”, presented in Lincoln’s famous 1863 Gettysburg Address. This was a connection that “Sun never failed to present, proudly, to any audience”.4

In the 1920s Sun proposed an immense infrastructure program of railways, roads and river projects for rapid agroindustrial and manufacturing development of all China. He advocated constant improvement of citizens’ livelihoods though public infrastructure, scientific progress, and technologically advanced transportation and agriculture, saying, “We must use the great power of the state and imitate the United States’ methods.”

Like Carey, Sun staunchly opposed British imperial policies, correctly predicting in his book The Vital Problem of China (1917) that if China joined the Allies in World War I, “whether the Allies will win or not, China will be Britain’s victim.” Britain, which financed loans to support Sun’s adversaries,5 divided China up as spoils of war at the post-WWI Versailles Conference.

Reflecting the nation-building beliefs of Lincoln and Carey, Sun wrote: “If we want China to rise to power, we must not only restore our national standing, but we must also assume a great responsibility towards the world. … If China, when she becomes strong, wants to crush other countries, copy the Powers’ imperialism, and go their road, we will just be following in their tracks. … Only if we ‘rescue the weak and lift up the fallen’ will we be carrying out the divine obligation of our nation.”

Today’s China continues Sun Yat-sen’s nation-building projects. In 2016 Chinese President Xi Jinping honoured Sun Yat-sen, declaring that Communist Party of China (CPC) members were faithful successors of Sun’s revolutionary undertakings, in pursuit of a “rejuvenated China that he had dreamed of”.

The new Great Game

In the 1990s China revived the idea of a “New Silk Road” or “New Eurasian Land-Bridge”, made up of ambitious rail and transportation projects. The Anglo-American powers reacted just as furiously against the prospect of sovereign nations cooperating to industrialise the Eurasian Heartland, as when the British Empire had conspired against Carey’s nation-building goals a century prior.

A pivotal conference took place 7-9 May 1996 in Beijing, themed “Economic Development of the Regions along the New Euro-Asia Continental Bridge”. Chinese speakers were joined by leading specialists from Iran, Russia and other Eurasian nations to discuss proposals for cooperation on ambitious infrastructure projects of high-speed railways, ports and agro-industrial corridors. Helga Zepp-LaRouche, founder of the international Schiller Institute, spoke on “Building the Silk Road Land-Bridge: The Basis for the Mutual Security Interests of Asia and Europe”, emphasising that the Land-Bridge could be the backbone of “a grand design for peace through development” and a cultural renaissance.

Also present at that event was Sir Leon Brittan, the former UK Home Secretary under Margaret Thatcher who was then the European Union’s commissioner for foreign relations. Eyewitnesses observed Brittan’s distress at Zepp-LaRouche’s speech and reported that he violated normal diplomatic behaviour in his zeal to disrupt the conference, threatening the Chinese with retaliation if they dared operate outside the global financial markets and the policy parameters of international agencies like the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organisation. In November 1996 former PM Thatcher herself travelled to Beijing for a conference on economics, where she inveighed against China for alleged human rights violations and provocatively referred to Taiwan as an independent county.6

As China’s Land-Bridge policy began to be realised, Gerald Segal of the UK’s flagship think tanks, the International Institute for Strategic Studies and the Royal Institute of International Affairs, campaigned against it. In a 1994 article for the New York Council on Foreign Relations journal Foreign Affairs, Segal presented a map of China reduced to about half its current size, dividing the rest into independent states of Tibet, East Turkestan (Xinjiang), Mongolia and Manchuria. (Similarly, Brzezinski’s 1997 Chessboard projected a break-up of Russia into three chunks.) The pompous Segal’s favourite theme was China’s coming irrelevance; his last article before dying in 1999 was “Does China Matter?” in Foreign Affairs. But shortly before the 1996 Eurasian Land-Bridge event in Beijing he came to Canberra to chair a conference, where he demanded a new Asia-Pacific “balance of powers” alliance to contain China.

In September 2013, speaking in Kazakhstan, Xi Jinping further developed the Eurasian Land-Bridge concept, unveiling his plan for “an economic belt along the Silk Road”. With the addition of the “Maritime Silk Road” concept, which he presented the next month in Indonesia, Xi’s initiative was named “One Belt One Road”, and then the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In the spirit of Henry Carey’s vision, it involves cooperation among more than sixty countries. Following Sun Yat-sen, it entails a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, ports, and other infrastructure in China, connecting to and developing the economic potential of Central Asia. No longer would this area of the continent be Mackinder’s geopolitical “Heartland”, as it would become a linchpin of the “Silk Road Economic Belt”.

China experts can recognise the BRI’s impact as a momentous shift towards new geoeconomic realities, absent in the old Great Game geopolitics. The authors of a 2018 paper, for example, discussed this shift in terms of a “New Great Game”, in which China shapes regional ties that influence the geopoliticians’ “Heartland” region in a primarily geoeconomic strategy—promoting trade, securing energy supplies and building cross-border infrastructure. China has become the largest trading partner of the Central Asia republics, the key region to reconnect Europe and larger Eurasia along the old Silk Road. These authors wrote: “China has built more highways, railroads, and bridges than any other country over the past two decades. Armed with this engineering expertise and construction experience, China has been building an extensive transport and municipal infrastructure projects in some of its Asian neighbours and faraway African countries. … While the original ‘Great Game’ carried a negative connotation regarding the territories controlled by both the British and Russian Empires, can a new ‘Great Game’ featuring China as the key player produce a different set of outcomes for all parties concerned?”7

The Xinjiang fulcrum

As a crossroad of the ancient Silk Road, Xinjiang has been a meeting place of many different cultures and faiths. It still is, with an ethnically mixed population of diverse religious background: as of the 2010 census, it was approximately 45 per cent Uyghurs, 40 per cent Han Chinese, 6.5 per cent

Kazakhs, and 2.5 per cent Hui. The Uyghurs and Kazakhs are Turkic peoples with a centuries-long religious tradition of Islam. “Hui Muslims” is a broad category, covering people of various ethnic origin who generally speak Chinese.

The region is still thinly populated, despite significant in-migration of Han Chinese under economic policies of the past 40 years of reforms. Xinjiang’s territory of 1.66 million km2 has a population of about 25 million: 15 people per square kilometre. For comparison, 83 million people live in similarly sized Iran, a population density of around 50 per square kilometre—more than triple that of Xinjiang.

At the 1996 Beijing Land-Bridge conference, nearly two decades before announcement of the BRI, Chinese official Gui Lintao from the ancient Chinese capital city and Silk Road terminus Xian, set forth a perspective for Xinjiang’s development on the “modern Silk Road”: “The Chinese government has … enabled a large number of demobilised officials and soldiers, young students, government officials and professionals from coastal and inland areas, to join the economic construction in the West. As a result, the Xinjiang railway line has been built up and a number of outposts, buried deep under the desert along the ancient Silk Road, are now shining like dazzling pearls along the Continental Bridge.”8

Speaking on China Arab TV in July 2019, Xinjiang regional government official Zhang Chunlin termed Xinjiang “the core region of the Silk Road Economic Belt”. He reported on its infrastructure development: “We have opened 111 [road] routes connecting with five surrounding countries. … In terms of railways, Urumqi has been connected to the hinterland’s high-speed rail network. The Hami-Ejina and Karamay-Tacheng railways have both begun operation. At the same time, we are building three new railways—the Korla-Golmud, Altay-Fuyun-Zhundong and Hotan-Ruoqiang lines. These three railways will add 2,013 kilometres to the growing regional network. In the past five years, a total of 925 kilometres of lines have been built…. By 2022, the length of railways in Xinjiang will exceed 8,000 kilometres. … Seventeen cross-border optical cables have been put into service in Xinjiang, connecting China with neighbouring countries such as Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.”

Zhang went on to detail Silk Road “dry ports” for trade with Central Asia and Europe through Kazakhstan, and other cross-border cooperation in industry, people-to-people exchanges, and soft infrastructure like science, medicine, and education. Xinjiang has reduced poverty by nearly 20 per cent and added half a million urban jobs annually in the past decade, according to official figures.

Xinjiang is strategically situated as the main overland gateway to Europe and Central and West Asia, functioning as the BRI’s “fulcrum” and the largest logistical centre of all countries within the BRI. It is the gateway for economic development of the heart of Eurasia.

The current Anglo-American assault against Xinjiang uses relentless propaganda, intelligence-agency-backed “human rights” crusaders and separatist insurgents, with the grim objective of destroying this fulcrum of the Belt and Road Initiative. Just as the British Empire conspired against Henry Carey’s vision, international media today are running a propaganda campaign to justify public censure and economic sanctions against China. British, American and Australian China-hawks aim to derail Xinjiang’s development and threaten its viability as the Eurasian Land-Bridge gateway to sovereign nation-building. Prosperity threatens the obsolete doctrines of geopolitics and balance of power.

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim (1901) popularised the term “Great Game”. Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia (NY: Kodansha International, 1992) is a thorough history of these 19th-century military and intelligence-agency struggles.

2. Anton Chaitkin, “The ‘land-bridge’: Henry Carey’s global development program”, EIR, 2 May 1997, details these international efforts.

3. Robert Barwick, “The Hamiltonian Revolution”, in Time for Glass-Steagall Banking Separation and a National Bank! (Australian Citizens Party: 2018) introduces American System principles of national economy. Available at citizensparty.org.au/publications.

4. Michael O. Billington, “Hamilton influenced Sun Yat-Sen’s founding of the Chinese Republic”, EIR, 3 Jan. 1992.

5. “British interests and Chinese nationalism”, UK National Archives, The Cabinet Papers.

6. Jeffrey Steinberg, “The Thatcher gang is out to wreck Clinton China policy”, EIR, 11 Apr. 1997.

7. Xiangming Chen, Fakhmiddin Fazilov, “Re-centering Central Asia: China’s ‘New Great Game’ in the old Eurasian Heartland”, Nature, 19 June 2018.

8. Excerpted in The Eurasian Land-Bridge: The ‘New Silk Road’—locomotive for worldwide economic development, EIR Special Report, 1997.