Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 2)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

Part 1 of this series, in the AAS of 18 November, sketched the history of the area in central Eurasia that today is China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Sitting astride the New Silk Road, Xinjiang is a target for Anglo-American strategists eager to destabilise China.

For most of three decades beginning in 1990, and particularly 1997-2014, there was unrest in Xinjiang, ranging from the seizure of government buildings by separatists demanding independence for Xinjiang as “East Turkistan”, to thousands of acts of terrorism, including car and bus bombings, assassinations of government officials and non-terrorist leaders in the Uyghur ethnic and Muslim religious communities, and attempts to hijack and blow up aircraft. Who were the groups that took credit for these acts? Where did they come from? In Part 2, we trace the Xinjiang destabilisation’s relatively recent roots in Anglo-American policies since the 1970s.

The British Empire fought in the 19th century to control the “Roof of the World”—central Eurasia, north of the continent’s high mountain ranges. The area was of strategic and economic importance, being traversed by the ancient Silk Road trade routes and famous throughout centuries, even before the discovery of enormous reserves of the fossil fuels and mineral resources used in modern industry, for its deposits of gemstones like jade (Xinjiang) and lapis lazuli (Afghanistan) and precious metals, including gold. But an overriding motive for Britain’s engagement in Eurasia’s central interior between 200 and 100 years ago was to block extension of the Russian Empire southwards to British India. More than a century of this military and intelligence-agency skirmishing, known as the Great Game, culminated in British geographer Halford Mackinder’s doctrine of “geopolitics” and its on-the-ground implementation, World War I. Part 1 showed how the geopoliticians’ insistence on the need to control the Eurasian “heartland” was driven by fear that major powers like Germany and Russia—with China potentially joining in—could develop Eurasia through transcontinental railway construction, thus challenging the sea-trade-based economic power of the British Empire.

In the 1970s the Great Game underwent a modern re-branding as the “Arc of Crisis” doctrine.

Bernard Lewis and Zbigniew Brzezinski

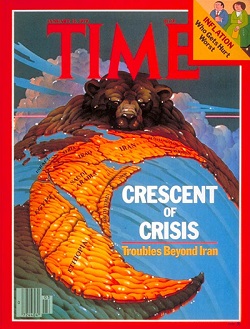

The new version of the old theory was officially launched by Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1978-79, as national security advisor to US President Jimmy Carter. The Islamic Revolution that would oust the Shah of Iran in 1979 was unfolding, but Brzezinski wanted to turn attention to Russia. Under the headline “Iran: The Crescent of Crisis” in Time magazine of 15 January 1979, he was quoted from a recent speech, warning that “an arc of crisis stretches along the shores of the Indian Ocean, with fragile social and political structures in a region of vital importance to us threatened with fragmentation. The resulting political chaos could well be filled by elements hostile to our values and sympathetic to our adversaries.”

The mastermind of the Arc of Crisis was a more shadowy figure: Bernard Lewis, a British historian of Southwest Asia and former intelligence officer.

After World War II stints in the British Army’s Intelligence Corps and then the Foreign Office, Lewis was based for 25 years at the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. In 1974, at age 57, he transplanted himself to the United States, accepting a Princeton University position with a light teaching load that allowed him maximum time for influencing American foreign policy. The October (1973) War between Israel and its Arab neighbours had just shocked the world, as an oil exports embargo by Arab oil producers sent prices skyrocketing.

Lewis churned out books on the history of Islam, with an emphasis on political aspects and potential conflict with the West. More and more, he promoted his vision of a fracturing of all the countries in the region from the Middle East to India, along ethnic, sectarian, and linguistic lines. Known as the Bernard Lewis Plan, this design was nearly identical to Brzezinski’s Arc of Crisis.

Lewis forced the Arc of Crisis onto the agenda of an April 1979 meeting of the secretive Bilderberg Group,1 just three months after the notorious Time magazine cover story. The meeting heard one paper titled “Implications for the West of Instability in the Middle East” and discussed the “arc of instability” from several angles.2 The presenter of the “Instability” paper cited ethnic tension as a major cause of it, enumerated ethnic minorities within countries across the region, and took note that many of these groups might seek autonomy. The behind-closed-doors discussants zeroed in on fears that the Soviet Union could obtain strategic advantages amid Eurasian instability, as well as such topics as how easy it is to induce American politicians to do something, if it appears to be standing up to Moscow. The aroma of Brzezinski’s scheme to turn Islamic ferment against the Soviet Union hung in the air.

In 1982 Bernard Lewis would be naturalised as a US citizen. In 1992 he updated the Bernard Lewis Plan for the post-Soviet period, foreseeing fragmentation and conflict throughout the Middle East and eastward into Eurasia.3 He was so closely identified with scenarios for American involvement in wars in this region, that he is also known as a “godfather of the neocons”, short for the “neoconservative” grouping that led the charge for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. On Lewis’s 90th birthday, in 2006, leading neocon warmonger Vice President Dick Cheney hailed him as the greatest living authority on the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire, and Islam.

Though not present at the 1979 Austrian meeting, Brzezinski was also a member of the Bilderberg Club, while simultaneously promoting his ideas through the Trilateral Commission (TLC). He had co-founded the TLC, which supplied several cabinet members to the Carter Administration. Both organisations are extra-governmental frameworks in which powerful financial interests and their political hangers-on regularly convene to thrash out strategies, which may then turn up as government policies in countries where they have control or leverage.

As noted in Part 1, Brzezinski also drew on the work of Sorbonne (Paris) Prof. Alexandre Bennigsen and other academics on the potential of Turkic and other Islamic insurgencies to slash up the “soft underbelly of the Soviet Union”. He was guided by his own ideology as a Polish émigré profoundly hostile to Russia, and as a follower of Mackinder’s geopolitics. Brzezinski’s fanaticism on these issues as a Carter Administration official made many Americans think he was crazy; average citizens called him Woody Woodpecker, while some analysts, alarmed by his geopolitical scenarios, dubbed him “Tweedledum” to his predecessor as national security advisor Henry Kissinger’s “Tweedledee”.

Later in 1979, Brzezinski would organise tangible American aid to Islamist fighters in Afghanistan—known as the mujaheddin—first against a Soviet-allied government that had seized power in April 1978, and then against Soviet forces directly, after they entered the country in December 1979. The weapons supplies and covert support from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) were code-named Operation Cyclone.

Geopolitics for the Cold War

The 1979 Soviet intervention in Afghanistan came at the end of a tumultuous decade. Its signature event was in August 1971, when US President Richard Nixon was induced by Wall Street interests to end the 1944 Bretton Woods monetary system, instituting floating currency exchange rates to replace the dollar reserve system with the US dollar’s value pegged to the price of gold. The new arrangement opened the floodgates to waves of financial speculation that haven’t ended since then, and the decoupling of finance from real economic development has provoked one economic crisis after another.

In 1973-74 the October War and subsequent oil price shock hugely boosted speculative flows in the so-called eurodollar market—American dollars circulating offshore, including through oil sales. In 1974 nearly every government in Western Europe fell, and President Nixon was forced out of office in the Watergate scandal. The United States was still extricating itself from more than a decade of war in Vietnam, which had caused turmoil at home and helped set the stage for Nixon’s ouster.

In this setting, the New York Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), little brother of the UK’s Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA or Chatham House), generated, out of its 1971-73 Council Study Group on International Order, a series of strategic studies named “Project 1980s”. One of its major themes was that the time had come for a strategic policy of “controlled disintegration”. Brzezinski’s Arc of Crisis and the Bernard Lewis Plan fit the bill.

What the CFR and allied strategists wanted to forestall above all was any bid to return to US President Franklin Roosevelt’s original conception of Bretton Woods and the post-World War II world: economic development of newly independent former colonies and peaceful relations with the Soviet Union, partner of the USA and its allies in the anti-fascist coalition. With the death of Roosevelt (FDR) in 1945, Winston Churchill and other leading British figures, with their henchmen in the USA, typified by the Dulles brothers (Secretary of State [1953-59] John Foster Dulles and CIA Chief [1953-61] Allen Dulles), engineered the Cold War.4 They fought viciously against any hint that a US President would revive elements of FDR’s legacy.5

Cold War anti-communism had landed the United States in Vietnam, the “land war in Asia”, against which Gen. Douglas MacArthur had sternly warned. The Cold War’s “red scare” hysteria, meanwhile, provided an excuse for Allen Dulles and his CIA, throughout the 1950s-1960s, to nurture certain long-term capabilities, which would be deployed decades later in Eurasia and elsewhere. These included a “stay-behind” network of former Nazi collaborators working under CIA and NATO control in Europe, called Gladio; it ran the period of coup plots and terrorism known as the strategy of tension, in 1970s Italy.6 Another set of organisations cultivated during these decades were ethnically defined “Captive Nations” and “Unrepresented Peoples”—groups of emigres from the Soviet Union and socialist Eastern Europe.

These capabilities came into play in the 1970s, when the Arc of Crisis policy frowned on any genuine East-West cooperation, like the huge deals West German leaders signed in Moscow in 1978 for the development of Siberia. The advocates of “controlled disintegration” preferred destabilising the Soviet Union, even at the risk of a global showdown and nuclear war. Zbigniew Brzezinski was the man for the job. There would be a “new and nicer” policy from the Trilateral Commission’s Carter Administration, dubbed “Project Democracy”, the forerunner of “colour revolutions” for regime change, and covert operations would be stepped up to subvert potential adversaries in the tradition of the Great Game, starting with Russia.

Operation Cyclone – Afghan Mujaheddin

The Soviet-allied People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, which carried out a coup in April 1978 against President Mohammed Daoud Khan (a cousin of the King of Afghanistan, whom they had supported Daoud Khan in overthrowing in 1973), was soon faced with resistance from various parts of the countryside, while faction fights and assassinations split the PDPA.

Chairing an October 1979 meeting with CIA officials, Brzezinski laid out the case for stepping up aid to these insurgents. According to State Department records, he “stressed the political importance of demonstrating to Saudi Arabian leaders that we were serious in opposing Soviet inroads in Afghanistan and the likelihood that a substantial commitment of assistance on our part would result in increased Saudi willingness to provide support.” The minutes report, “The committee concluded by endorsing unanimously a proposal for [amount not declassified] of additional aid for Afghan rebels, to be provided primarily through Pakistan and Saudi Arabia in the form of cash, communications equipment, non-military supplies and procurement advice.”7

On 26 December 1979, the day after Soviet Airborne Troops had landed in the capital, Kabul, and the day before Soviet ground forces moved into the country, Brzezinski wrote a memo to President Carter, motivating stepped-up weapons and other support to the insurgents. He argued explicitly that the USA must play the role Britain had played during the Great Game, to prevent fulfillment of “the age-long dream of Moscow to have direct access to the Indian Ocean”.8

Amid debate years later over whether or not the United States had deliberately lured the Soviet Union into Afghanistan, Brzezinski admitted that he had wanted to do exactly that. Asked by a French reporter whether the Carter Administration had wanted to “provoke” a Soviet intervention, Brzezinski replied, “It wasn’t quite like that. We didn’t push the Russians to intervene, but we knowingly increased the probability that they would.”

Asked if he regretted those actions, Brzezinski doubled down: “Regret what? That secret operation was an excellent idea.” This referred to a Brzezinski-inspired secret “finding” by President Carter in July, which served as the go-ahead for aid to the insurgents, six months before the Soviet intervention.

Said Brzezinski, “It had the effect of drawing the Russians into the Afghan trap and you want me to regret it? … [F]or almost 10 years, Moscow had to carry on a war that was unsustainable for the regime, a conflict that bought about the demoralisation and finally the breakup of the Soviet empire.”9

Operation Cyclone, lasting 1979-89, was financed at up to US$630 million a year. Often the funding was matched by Saudi Arabia, for a total of around $1 billion.10 Britain’s intelligence agency, MI6, engaged alongside the CIA’s Operation Cyclone in Afghanistan, in covert training and support for guerrilla operations and, increasingly, radical Islamist fighters.

‘He who sows the wind…’

From the middle of the Operation Cyclone period dates al-Yamamah, the $48 billion Anglo-Saudi oil-for-arms deal, Britain’s biggest arms contract ever, arranged in 1985 by former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan. Later stages of al-Yamamah were negotiated by Bandar’s close personal friend, Prince Charles. Under al-Yamamah, British defence contractor BAE Systems supplied fighter jets and infrastructure to the Saudi Air Force in exchange for 600,000 barrels of oil per day—one full oil tanker—for every day of the life of the contract, which as of 2005 had netted BAE Systems £43 billion. Beyond that declared profit, al-Yamamah generated a secret US$100 billion-plus off-the-books slush fund, which was used to finance coups d’état, assassinations, and terrorism—including the creation of the al-Qaeda terror network in Afghanistan and, ultimately, al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks in the USA.11

It is no secret that Anglo-American cultivation and backing of the mujaheddin in Afghanistan gave rise to al-Qaeda and, later, the so-called Islamic State (ISIS). British author Mark Curtis, in his 2011 book Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam (Profile Books: 2010), documented decades of British intelligence collusion with terrorists, including al-Qaeda.

The battlefield support against Soviet forces in Afghanistan was paralleled, and augmented, by a massive Saudi program to build mosques and Islamic schools worldwide, to promote a radical form of Wahhabism, the state religion in Saudi Arabia. This deliberate spread of Wahhabism became a major source of terrorists throughout the Middle East, the Caucasus region, and into Central Asia, as our Part 5 will describe.

Zbigniew Brzezinski didn’t mind. “Do you regret having supported Islamic fundamentalism, which has given arms and advice to future terrorists?” the French reporter asked him in 1998. Brzezinski replied, “What is more important in world history? The Taliban [Islamist radicals in Afghanistan] or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some agitated Moslems or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the cold war?” That is typical geopolitical thinking.

The detrimental outcomes of covert CIA support for terrorist insurgencies were well summarised by American Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard (Democrat of Hawaii) in a January 2017 speech: “Under US law it is illegal for any American to provide money or assistance to al-Qaeda, ISIS or other terrorist groups. If an American citizen gave money, weapons or support to al-Qaeda or ISIS, he or she would be thrown in jail. Yet the US government has been violating this law for years, quietly supporting allies and partners of al-Qaeda, ISIS, Jabhat Fateh al-Sham and other terrorist groups with money, weapons, and intelligence support, in their fight to overthrow the Syrian government. The CIA has also been funnelling weapons and money through Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Qatar and others who provide direct and indirect support to groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda.”12

In Part 3: Xinjiang becomes a target

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. “Bilderberg cult plots oil war: EIR publishes scheduled attendance at Austrian gathering”, Executive Intelligence Review, 24 April 1979. The participants’ list and information about Lewis’s intervention for the agenda change were conveyed to EIR by a source in Europe before the meeting took place.

2. A document labelled “Bilderberger Meetings: Baden Conference, 27-29 April 1979” is posted on wikispooks.com under the heading “Bilderberg Conference Report 1979”. Its authenticity is not verifiable from that source, but the participant list, texts and discussion summaries are consistent with what EIR had reported days beforehand.

3. Bernard Lewis, “Rethinking the Middle East”, Foreign Affairs (New York Council on Foreign Relations), Fall 1992.

4. The British Empire’s European Union, Citizens Electoral Council of Australia pamphlet (2016), gives a history of the Cold War’s launch.

5. Anton Chaitkin, “The coup, then and now”, Australian Almanac, Vol. 8, Nos. 14-18 (2017), tells this story.

6. Claudio Celani, “Strategy of Tension: The Case of Italy”, EIR dossier, March-April 2004; Allen Douglas, “Italy’s Black Prince: Terror War against the Nation-State”, EIR, 4 Feb. 2005.

7. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977–1980, Volume XII, Afghanistan, Office of the Historian, US Department of State.

8. Zbigniew Brzezinski, “Reflections on Soviet Intervention in Afghanistan”, Memorandum for the President, 26 Dec. 1979, held in the National Security Archive at the George Washington University.

9. Interview with Le Nouvel Observateur (Paris), 15-21 Jan. 1998, tr. by William Blum and David N. Gibbs. It is online at dgibbs.faculty.arizona.edu/brzezinski_interview.

10. Barnett R. Rubin, The Fragmentation of Afghanistan, Yale University Press, 1992.

11. To Stop a Near-term Terror Attack, Read the ’28 Pages’! (2016) and Stop MI5/MI6-run Terrorism! (2017) are Citizens Electoral Council pamphlets, containing detailed histories and consequences of al-Yamamah. At citizensparty.org.au/publications.

12. ”Stop Arming Terrorists”, 13 Jan. 2017, gabbard.house.gov.