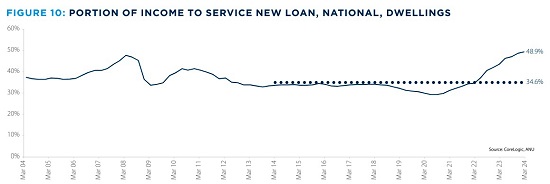

Australians are now spending a whopping 48.9 per cent of (median) income to service a home loan on a median priced property, according to the April 2024 ANZ CoreLogic Housing Affordability Report. In Sydney that figure has soared to just under 60 per cent; in regional NSW it is 55.4 per cent.

This number is at a record high, well above the average of the previous decade, of 34.6 per cent. With house prices still rising, despite “inflation-fighting” interest rate austerity, the “affordable purchase price [for most families] is below most actual dwelling values, with the median Australian unit price around $640,000, and the median house price around $834,000 across Australia”, says the ANZ Corelogic report.

And making light of the renter’s plight with the catchy title “30’s are the new 20’s”, the report says that “the portion of income required to service rents has shifted to the 30 per cent range from the mid-20 per cent range for median income earners in most parts of the country”. Some low-income earners are spending 54.3 per cent of income on rent.

Greens proposal

While there have been various offerings, no effective policy proposal has been made by the Albanese government to address Australia’s housing crisis, because they are all subject to the strictures of neoliberal dogma and are designed to work by incentivising private players under the market-based model. But the Greens have put up a more interesting idea. On 6 March, Greens MP Max Chandler-Mather announced the Greens housing policy for the next federal election, calling for “a public property developer that would build, sell and rent homes at a price that people can actually afford.”

The Greens say the public developer could build 360,000 homes in five years, and 610,000 over a decade. At a price “just above the cost of construction”, 30 per cent of the homes would be available for purchase by first home-buyers, and 70 per cent made available to rent, with rents capped at 25 per cent of household income, according to a tweet by Chandler-Mather.

The public developer would compete with private developers, breaking their monopoly and exerting downward pressure on prices. Renters would be saved around $5,200 per year on rent, wrote Chandler-Mather, with buyers saving an estimated $260,000.

The Greens will also scrap tax breaks for property investors. “The housing crisis is breaking people. But to fix it—we need to break the control the property industry has over our political and economic system”, said Chandler-Mather.

A model that works!

For this proposal to work, a proven model should be employed. AAS has previously written about the strategy utilised by South Australia, and nationally under Ben Chifley’s 1945 housing program, most recently in “Labor’s National Housing Accord is just another neoliberal fraud”, AAS, 16 Nov. 2022.

Notably, the South Australian housing program, commencing in the mid-1930s, was not the design of some socialist premier, but was brought into being by a conservative Liberal and Country League state government, and most effectively deployed by Sir Thomas Playford IV, premier of the state in 1938-65.

The vehicle for the program, the South Australian Housing Trust (SAHT), was established as a statutory agency in 1936. Effectively a state-owned company, it operated as a planning and development authority for the state, rolling out infrastructure from roads to playgrounds and even new cities. It built a third of all South Australian homes in 1945-70. At its peak, the SAHT became the state’s biggest property developer, generating its own revenue stream and costing the taxpayer nothing. It was also the biggest landlord to renters but charged only “economic rents” rather than market rates, fixed at one-fifth to one-sixth of income. Compare that to today’s 50 per cent plus proportion of income spent on rent.

The same approach to public housing was adopted by Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley, who used the Commonwealth Bank to fund the first Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement (CSHA) beginning in 1945. Loans were provided to State housing authorities to build housing for low-income families, but the program was gradually deconstructed by the Menzies Liberal government which took power in 1949.

The State Bank of Victoria

Even earlier than these examples came Victoria’s housing program. The State Bank of Victoria, owned by the state government, started off as the Savings Bank of Port Phillip in 1842. It was reconstituted in 1912 as the State Savings Bank of Victoria.

According to a speech given by Arnold Atkinson, at a Probus Club of Melbourne gathering in the 1990s, the bank was an innovator in a number of fields, including farm loans, and housing loans plus accompanying building standards. Atkinson started as a junior clerk at one of the bank’s branches and went on to become Deputy General Manager responsible for financial operations of the bank.

In the mid-1890s the bank established its Credit Foncier Department, he said, which allowed farmers to borrow for periods of up to 20 years and repay their loans in fixed halfyearly instalments at reasonable rates of interest. Credit foncier is a French term which refers to a fixed-period loan with regular repayments that include components of both principal and interest. Prior to that, farmers could only access trading bank overdrafts that were repayable upon demand, or short-term mortgage loans. “During this period there had been many foreclosures”, wrote Atkinson.

In 1910 the same principle began to be applied to housing loans, through the Credit Foncier Department. Atkinson described how the project evolved:

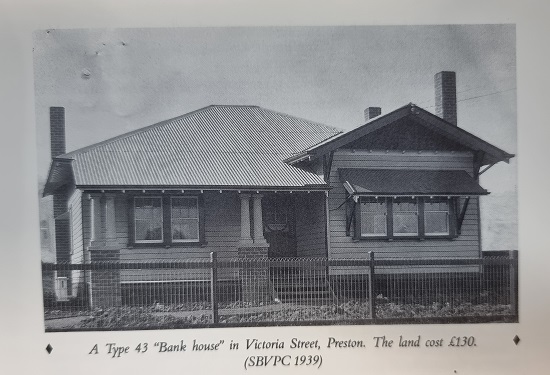

“In 1921, a Chief Architect was appointed to head up a Building Department, employing architects, clerks of works and valuers. By the mid-twenties the Bank had become the biggest home builder in the State. In the absence then of any building regulations, the bank set the standards for home building with its rigid specifications of the best materials and best supervision, carried out under supervision by its clerks of works.

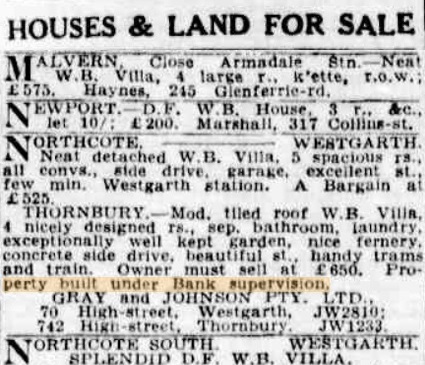

“Some of the suburbs developed in the twenties bear the bank’s imprint in every street. The most fetching line in the estate agent’s advertisement in those days was, ‘built under Bank supervision’. There was no need to ask ‘which bank?’ Everyone knew.

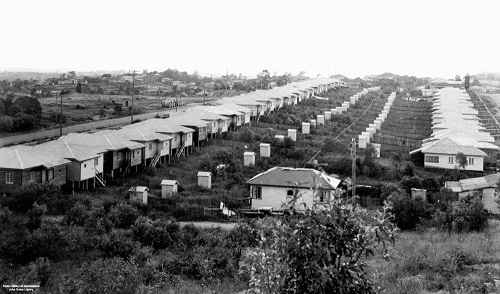

“Garden City, near Port Melbourne, was a major development completely carried out by the Bank in 1926 as an experiment in community living after the style seen by the Chief Architect in England.”

The bank already had some experience in this area, administering Victoria’s War Service Homes scheme for returned servicemen after the close of WWI. Now, “the Bank effectively became a builder in its own right, issuing standard designs and selecting building contactors for many of the houses it financed”, wrote the authors of A bank for the people, Robert Murray and Kate White (Hargreen, 1992). “A ‘Bank home’ became an affordable goal”.

With the 1920 Housing and Reclamation Act, the bank no longer solely provided finance for homes, but supervised construction from start to finish. Based on the findings of the 1914 royal commission into housing conditions, the Act empowered the Bank to purchase land and to erect homes for disadvantaged citizens, at a capped cost. General Manager of the Bank, George Emery, travelled to England—as would others from the bank—to inspect public housing projects, to “ascertain the best and most economical methods of supplying dwellings to people of small means”, as instructed by the bank’s commissioners.

A bank for the people noted: “The act used the simple financing device of giving a government guarantee to the extra debentures required to expand the existing credit foncier services. They thus had a status equivalent to state bonds.” Funding also came from the expanding deposits in the Savings Bank Department.

In 1922-23 the Credit Foncier Department built nearly 5,000 homes; thousands more would be built in the ensuing years. All were occupied by their new owners whose home loans drew around one-fifth to one-quarter of their average weekly income. According to A bank for the people, there was a marked improvement in the quality of materials utilised and workmanship, even in these cheaper homes. Previously they had been constructed by “speculative builders”, so dubbed by head of the Bank’s Building Department, Burridge Leith. Now, “large numbers of public houses are being turned out rapidly to meet an urgent public need”, Burridge, an architect, told the Herald (Melbourne) in February 1924, but “the term ‘jerry-built’ does not apply to these structures. All the houses must pass a rigid test and we know that they will stand the further test of time.”

Despite the postwar shortage of building materials, and other problems including wood borers, houses popped up all over Melbourne. The Bank experimented with different building materials and methods. So successful was the program that “By 1924 the Bank’s funds could not match the demand”, summed up A bank for the people.

Victoria most advanced ‘in world’

A major initiative of the Bank was Garden City, a residential housing scheme modelled on English examples, built at Fisherman’s Bend, near Port Melbourne, so that wharf workers and their families didn’t have to crowd into dingy single rooms or the men cycle home at midnight in darkness when there was ample potential land for housing.

“The basis of the Victorian scheme is home-ownership for the people, and here it has probably been developed further than in any other part of the world, and there is not the slightest doubt that it gives a great sense of security and domestic responsibility to the people as a whole”, the Herald of 23 December 1925 relayed Bank Manager George Emery’s comments after returning from a world tour to examine home-building methods abroad. The Fisherman’s Bend project, with architect-designed homes, road layout, fencing and sewerage all contracted by the bank, was overwhelmed with applications.

Sir William McBeath, chairman of the bank’s board of commissioners, noted the new era of town planning it represented, saying every man “should try to possess a home. It made for the stability of the country generally, and made people take an interest in the Government and finance of the country.”

For the Victorian government, this marked a “transition from laissez-faire to interventionist attitudes in housing Victorians”, noted the book, which would be continued during and after the Depression. “The Bank’s role in the 1920s preceded and foreshadowed that of the Housing Commission and the private enterprise estate builders, which both emerged after the 1930s Depression.”

After a decade of successful home loans, the bank began to issue other concessional loans for lower income workers and veterans. It was becoming a useful instrument of the government’s social policy, according to the authors of A bank for the people. Unfortunately, the neoliberal economic notions that increasingly took hold in the 1970s and ’80s included the mania for financial deregulation which swept the State Bank into increasingly risky banking activity. This financialisation—documented in “Financial deregulation propels Kennett’s rise”, AAS, 17 April—sounded the death knell for the bank, and crucial economic functions such as building housing.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 1 May 2024