In the last two years the realisation of how crucial public services are to a functioning economy has hit like a tonne of bricks. We were found severely lacking in numerous capacities such as basic public health functions. State governments hustled to pick up the slack, but all the federal government was able to do was “sign cheques and send in the military”, in the words of University of Queensland Economics Professor John Quiggin. After allowing a slight uptick in public service jobs at the height of the pandemic, the Morrison government immediately returned to its downsizing. What gives? As usual, economic ideology.

Among the Labor Party’s election promises was its “Plan to Improve the Public Service”. It pledged to abolish arbitrary caps on staffing levels, reduce the reliance on external contractors, consultants and labour hire companies, converting them into permanent public service jobs, and target the “scourge of insecure work”.

As part of this, an audit will be conducted, Labor said, to reveal the composition of employment in the public sector. Currently there is no database tracking the use of labour hire or contracting services at the federal level, but a 2021 review of the Australian Public Service revealed the destructive impact of outsourcing public sector work. (“Senate inquiry slams sabotage of public service”, AAS, 2 Feb.)

The ALP claims it will reduce spending on external workforces by $3 billion over four years, cutting by 10 per cent in the first year. It will invest $500 million to rebuild public service capabilities, creating over 1,000 new positions at service delivery agencies including the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the National Disability Insurance Agency.

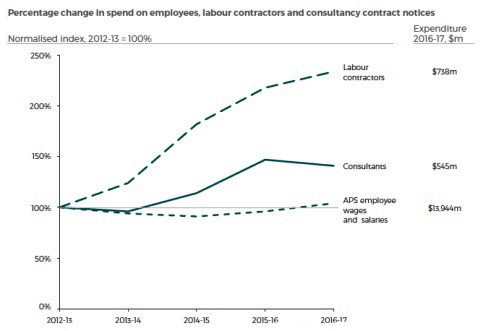

Reviews of the federal public service by the government and National Audit Office show that spending on consultants alone more than doubled since 2013; external labour usage by the federal government doubled in just the last five years at a cost of more than $5 billion per year. The 2019 Thodey Review of the public service recommended removal of staffing caps to reduce reliance on external labour. Former Australian Public Service Commission boss Andrew Podger endorsed Labor’s plan to remove the staffing cap, saying “the excessive use of consultants has been a contributor to the loss of strategic policy advising within the public service”.

Labor expects to save money from its reduction in outsourcing, but will maintain the “efficiency dividend” required of the public service at the current level of 1 per cent. The efficiency dividend is an automatic annual budgetary reduction based on the expectation of greater efficiencies including automation and digitalisation of services. Just prior to the election the Morrison government announced it would increase the dividend by 0.5 per cent—i.e. deepening the annual budget cut— to save an extra $2.7 billion from the budget over four years.

According to the Australian Parliamentary Library, the efficiency dividend, adopted by Prime Minister Bob Hawke in 1987, incentivises the public service to be more efficient, given that “the public sector does not face the same incentives as the private sector to pass on gains from increased productivity in the form of lower prices”. A specialist in government service delivery in both New Zealand and Australian governments, Pia Andrews, has noted that a lot of outsourcing is done “just to meet an efficiency dividend”.

Ideological shift required

Restoring the public service will take more than what Labor is promising. With the rise of neoliberalism came propaganda that the private sector is infinitely more efficient than the public sector, blocking out the reality that the functions of government are oriented to the public good over the extremely long term, not profit motives and other short-term measures of success.

A push to delegate public policy making began in earnest in the 1990s. It originated with a doctrine known as New Public Management, which had started to form in the late 1970s, driven by efforts, particularly under the Prime Ministership of Margaret Thatcher, to reverse the growth of government and increase privatisation and globalisation. According to a definitive 1991 paper, “A public management for all seasons”, by Oxford Professor of government and public administration Christopher Hood, businessstyle “managerialism” was to be applied to the public sector, with the policy shift most coherently elaborated in the New Zealand Treasury’s 1987 Government Management report. This is not surprising—New Zealand was a model for the post-war free market revolution planned by the British-crown funded global economic warfare unit, the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS).

In Australia a series of Royal Commissions, Commissions of Audits and Budget Reviews from the mid-1970s recommended a barrage of economic reforms, dictated by the Australian think tanks associated with the neoliberal MPS. (“Outsourcing government is a corporate takeover”, AAS, 23 Sept. 2020). Within that framework, New Public Management was essentially privatisation of government itself, by stealth, delivered directly by outsourcing and indirectly, by implanting a private sector mentality into the public service. It was designed to have universal appeal to both sides of politics and to be applicable to all fields of governance.

With NPM came “performance indicators”, playing upon public concerns regarding waste of public resources. As Hood wrote, it also brought “‘just-in-time’ inventory control systems (which avoid tying up resources in storing what is not currently needed”, implemented “paymentby-results reward systems”, and “administrative ‘cost-engineering’ (using resources sparingly to provide public services of no greater cost, durability or quality than is absolutely necessary for a defined task”.

Drowning out the voice of citizens

There was a commensurate shift, Hood wrote, to “new machine politics”, that is, “making public policy by intensive opinion polling of key groups in the electorate, such that professional party strategists have greater clout in policy-making relative to the voice of experience from the bureaucracy”.

The human capabilities of the public service, required not only day-to-day but in the event of an emergency, were stripped. (See for example “Lismore community fights for effective flood management”, AAS, 23 March. The skill and knowledge of Lismore locals was superseded by centralised authorities with no connection to events on the ground. The more efficient and cheaper “market” approach is clearly not always more effective.) Outsourcing means the loss of vital capabilities of people who comprise a crucial part of governing the nation. As public service expert Pia Andrews wrote in “New Public Management: the practical challenges, remedies and alternatives” (The Mandarin, 21 Nov. 2019), social workers helped develop the NZ Social Service Act “because it used to be normal practice to have what we’d now call cross-functional experts be part of the policy development process”. Andrews bags the notion that because it provides the right incentives, “the free market can solve all problems and that government should just get out of the way”. The development of legislation—the rules upon which society depends—”is clearly a public sector role”, she states.

The public sector is crucial to ensure the long-term thinking required to secure the future of the nation, Andrews wrote, “because [the public service] can do so at a scale, and can deal with a high level of system complexity, for increasingly diverse needs, can do so sustainably and are motivated by a public good imperative. Taking a duty of care approach means necessarily taking a systems approach, and long term in public sector terms means decades or centuries and public sectors can provide a platform upon which the whole society and economy can thrive. Of course, when public sectors acted more and more like private sectors, this became difficult to discern.”

The shift associated with NPM has pushed community out of governance, outsourcing functions that have impacts beyond the economy, including on social cohesion, protective standards and safety nets, and, says Andrews, “we lose the public sector voice of sustainable public good, and we lose the possibility of ensuring policy positions that are codeveloped with citizens”. Public servants, comprising a diverse group of a couple of million experts with valuable practical experience, have thereby been effectively silenced from public participation in policy.

Private sector managerialism and its adherence to financial bottom lines, benchmarking, economic outcomes and “customer” metrics has destroyed real world outcomes for real people; marketing doublespeak has destroyed communications with the public, especially crucial in times of crisis. Patients, students and veterans, all “customers” under the new framework, do not receive the specialised support they require. A focus on competition in the marketplace has led to the hollowing out or outright loss of vital structures such as the original TAFE (Technical and Further Education) system. Reliance on external consultants has led to a dangerous loss of institutional memory and expertise. Writing about recent failings of the federal government encapsulated by Morrison’s “I don’t hold a hose” attitude, in a September 2021 piece published by The Monthly, “Dismembering government”, Professor Quiggin noted that efforts to impose external “management” on the public service were doomed to fail because management of services cannot be separated from delivery of services: “Much of the knowledge required for policy management is tacit and shared by the professional and vocational employees who actually do the work.”

Undo the sabotage!

Think of the kind of expertise required to manage a hospital and its day-to-day functions. New Public Management has infected the public health system, leaving our hospitals in a dangerous position. On 13 May a senior trauma doctor at Melbourne’s Alfred Hospital, and outgoing president of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Professor John Wilson, quit his position in protest at Victoria’s deteriorating healthcare system. He forecast a mass exodus of burnt-out doctors and nurses unless there is dramatic change. Professor Jan Carter of Deakin University, who was involved in the Victorian Department of Health reviews conducted by Victorian state governments under Premiers Cain, Kennett and Bracks, has reported how New Public Management caused this disaster.

It has no doubt affected emergency service functions. A just-completed review of the Emergency Services Telecommunications Authority (ESTA), the statutory authority that connects people to emergency services, has demanded change to governance structures, oversight and the funding model. But true to form, the independent “expert” advisor engaged to assist the review was private Big Four consultancy firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC).

Another neoliberal weapon against the public service is National Competition Policy. Designed by Macquarie Bank executive Fred Hilmer in 1991, NCP determined to take away the government advantage in service provision, to ensure a level playing field for private competitors. Academic research says “competitive neutrality” forces government agencies, including hospitals, to bear the same costs and obligations “as if they were in private ownership”—to induce competition and improve internal efficiency. This approach is inspired by “economic theories” that move the public sector “towards market principles”, to “lower costs, and to ensure that public sector instrumentalities become smaller, more efficient and more productive”. (“Outsourcing and benchmarking in a rural public hospital: does economic theory provide the complete answer?”, Suzanne Young, Deakin University.) The financial statements of hospitals even reference the policy, such as that of Peninsula Health, Frankston Hospital, 2003: “The aim of the competitive neutrality policy is to ensure that where government’s business activities involve it in competition with private sector business activities, the net competitive advantages to accrue to a government business are offset.”

As seen in other fields, from retail to banking, this mentality has in fact eroded competition, whereas a cheaper government competitor would force the private sector into line. In reality competition has also meant higher costs and lower efficiency, as seen in PM John Howard’s decision to align Australian fuel prices with higher prices overseas, for no good economic reason. (“John Howard’s ideological scam in 1978 that gouges Australian drivers to this day”, AAS, 27 April.) This is not the free market, but rigging in favour of the private sector!

Anthony Albanese has said he will take his lead from Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. But it was they who ushered in these neoliberal policies after Whitlam was dismissed and the Labor Party succumbed to the same ideologies that had swept the Liberal party at the hand of the Mont Pelerin Society. If Labor wants to restore the public service it has some soul-searching and realignment of ideology to do.

By Elisa Barwick, Australian Alert Service, 25 May 2022