Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 5)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

Parts 1–4 of this series appeared in the AAS of 18 November and 2 and 9 December 2020, and 20 January 2021. References to those articles are given in parentheses in this one.

The “Pan-Turkic” movement promoted by British Intelligence in the 19th century (Part 4, section “The Young Turks”) included a “Pan-Islamic” element, as it sought to turn the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, as “caliph”—the steward of Muhammad, into a rallying point against Russia in Eurasia. In 1869 the Young Ottoman newspaper Hurriyet (Liberty) criticised the Ottoman Empire’s leaders for failure to defend the Islamic Turkic peoples of Central Asia.

In the Pan-Turkist revival of the early 1990s after the break-up of the Soviet Union (Part 4, “Post-Soviet Pan-Turk revival”), the radical Islamist component was greatly amplified by the results of Anglo-American cultivation and backing of the mujaheddin guerrillas, fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan in 1979-88 (Part 2, “Operation Cyclone—Afghan mujaheddin”).

Wahhabite education, jihadist training

Besides money and weapons, support to the mujaheddin had an organisational side: training camps, negotiation of political alliances, and education. Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, which were co-funding the mujaheddin, had major input into all of these aspects. Anything that would feed violent action against the Soviets was fair game, including violent jihad—struggle against those identified as enemies of Islam.

The international sponsors supplied religious literature to schools in 1980s Afghanistan: millions of US government dollars funded textbooks for schoolchildren that were filled with anti-Soviet text, violent images, and promotion of jihad and militant Islamic teachings. The books were designed by the Centre for Afghanistan Studies (CAS) at the University of Nebraska-Omaha, which received US$51 million in government grants for education programs in Afghanistan in 1984-94.1 (Another one of its funders, the oil company Unocal, was evidently looking forward to contracts in post-war Afghanistan.) Religious textbooks in languages spoken in Afghanistan also went to madrassas (religious schools) located in Pakistan.2

Saudi Arabia, a major partner in funding the mujaheddin, had begun in the previous decade a worldwide program of proselytising with its brand of Islam, called Wahhabism. The deadly consequences of this Saudi campaign are no secret, as is expressed in the title of a report commissioned by the European Parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs in 2013: “The Involvement of Salafism/Wahhabism in the Support and Supply of Arms to Rebel Groups around the World”.

Saudi Wahhabism dates back to the 18th century, when ancestors of the founding prince of the House of Saud, Abdulaziz Ibn Saud (1876-1953), allied with Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, who claimed to preach a pure doctrine of return to the fundamentals of Islam. Today Wahhabism is considered a branch of the Salafi movement, which emerged in Egypt and elsewhere in the 19th century as a fundamentalist tendency within Sunni Islam. Many Salafists have been peaceful and apolitical, but there is a fanatical Wahhabite interpretation of the obligation to kill non-believers and apostates that fits neatly into campaigns to promote violent jihad.

The House of Saud has been interwoven with British Intelligence since its inception. In 1922 then-Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill put Ibn Saud on the payroll at £100,000 a year, later writing that “my admiration for him was deep, because of his unfailing loyalty to us”. In 1927 King Saud ceded to Britain control over the emerging state’s foreign policy. Meanwhile, the King struck a pact with the Al ash-Sheikh clan, descendants of al-Wahhab, giving them the power to administer and oversee religion and law in the Kingdom. This alliance remains in effect. The powerful Saudi Ministry of Religious Affairs, de facto headquarters of the Wahhabites in Saudi Arabia, has poured billions of dollars, through ostensible charities and other religious institutions, into establishing Wahhabite madrassas and mosques, and cultivating influence, around the world.3

The spending spree began in the mid-1970s, when Saudi Arabia was awash in “petrodollars”, proceeds of the manipulated oil-price rise of 1974. It got a big boost in 1985 from the al-Yamamah oil-for-arms deal between Saudi Arabia and UK weapons maker BAE—a personal project of Prince Charles, alongside then-PM Margaret Thatcher—which created a US$100 billion slush fund for off-the-books operations (Part 2, “He who sows the wind…”). Estimates of Saudi spending to promote Wahhabism in the three decades after 1975 run as high as US$75 billion.4

The Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation, a Saudi NGO, was banned worldwide by the United Nations in 2004 for “participating in the financing, planning, facilitating, preparing or perpetrating of acts or activities by, in conjunction with, under the name of, on behalf or in support of al-Qaeda” and other terrorist organisations. According to the above-cited Europarliament report, al-Qaeda operatives sitting in leadership positions in such Islamic charities diverted 15-20 per cent of their funds to finance terrorists; in the Philippines, this figure reached 60 per cent.

Tens of thousands of Saudi-financed madrassas were built in Pakistan. During the period of Operation Cyclone, the CIA’s covert funding of the mujaheddin (Part 2), Pakistan was ruled by Gen. Zia ul-Haq, who had overthrown PM Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1977 and had him executed in 1979. Pakistan received US$3.2 billion in direct aid from the USA, as it became the conduit for Operation Cyclone operations.

Inside Afghanistan in the 1980s, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) helped to set up several mujaheddin groups, known as the Peshawar Seven after a city in Pakistan near the Afghanistan border, for combat with the Soviet troops. At the same time, Pakistan served as a logistical base for the mujaheddin.

The Saudi-sponsored madrassas in Pakistan operated as anti-communist recruitment centres for jihad against the Soviets, which fed into an array of new operations in Afghanistan and abroad after the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Part 3, “Mujaheddin fan out”). Some of them were Arabs, recruited through Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK, a.k.a. “Afghan Services Bureau”), an organisation with offices in Peshawar and close ties to the ISI. MAK had been founded in 1984 by a group including future al-Qaeda leaders Osama bin Laden (Saudi) and Ayman al-Zawahiri (Egyptian) to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.5

The Central Asia blueprint

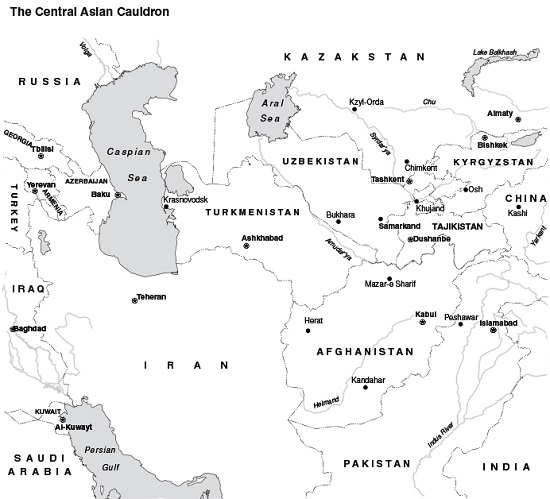

After 1991, the Anglo-American powers turned their attention to the former Soviet republics of Central Asia, as well as the North Caucasus region of Russia itself, seeking to disrupt Russian and Chinese influence in the region and clear the way for foreign control of its energy and other resources. The utilisation of the ex-mujaheddin in these efforts is acknowledged even by Washington insiders like Yossef Bodansky, former director of the Congressional Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare. In a 2000 article, Bodansky wrote that Washington was conducting “yet another anti-Russian jihad … seeking to support and empower the most virulent anti-Western Islamist forces”. He described “Washington’s tacit encouragement of both Muslim allies (mainly Turkey, Jordan and Saudi Arabia) and US ‘private security companies’... to assist the Chechens and their Islamist allies to surge in the spring of 2000 and sustain the ensuing jihad for a long time.” Sponsorship of “Islamist jihad in the Caucasus” would be a way to “deprive Russia of a viable [oil] pipeline route through spiralling violence and terrorism”.6

Afghanistan in the 1990s also became a major source for the world’s narcotics trade and the associated cash flows, which have become an integral part of the global financial system. It took over from Southeast Asia the status of number one supplier of heroin. The money could be used for financing terrorism as well.

Battle-hardened mujaheddin fighters engaged in coups, massacres of civilians and terrorist operations in Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Balkans throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. Radical Wahhabite ideology ran rampant, spread through Saudi financing of Wahhabi mosques in Bosnia and Kosovo, and through al-Qaeda and other successor organisations to the mujaheddin.

By 2000, President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan would complain, “Afghanistan has become a training ground for terrorists. If the Afghans themselves were allowed to settle their problems, there would have been peace long ago. Geopolitical and strategic centres are continuing to add fuel to the fire of this war [he was referring to “bandit” attacks in the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan-Tajikistan border area] and the end is not in sight.”7

The radical Islamist Taliban militia, which seized and held power in Afghanistan in 1996-2001, arose from the Anglo-American-Saudi-supported mujaheddin and their training camps and schools in Pakistan. So did the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), a terrorist group operating in Central Asia, though its founders in 1998 were Uzbek-ethnic veterans of the Soviet intervention force in Afghanistan. The radical fundamentalist group Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT), operating throughout the Middle East and Central Asia from its base in London, supplied much of the manpower for the IMU.8

Several nations have moved to restrict Salafism, because of its serving as an ideology for terrorist groups. In 2013, a Russian court banned a Salafi interpretation of the Qur’an (although other versions are permitted), designating it illegal for promoting extremism by asserting the superiority of Muslims over non-Muslims, positive evaluation of hostile actions against non-Muslims, and incitement to violence. Kazakhstan moved to ban Salafist activity after a series of terrorist attacks in 2016. In Germany, Salafist mosques were banned after members were found to be planning terrorist attacks and preparing to travel to Syria to fight for the Islamic State (ISIS).

Pakistani madrassas recruited Xinjiang Uyghurs

American diplomats, meeting in the 1980s in Pakistan with representatives of the Peshawar Seven, saw a map on the wall of their office, on which Soviet Central Asia and Xinjiang were labelled “Temporarily Occupied Muslim Territory”.9

According to Graham Fuller, the CIA officer working on Turkey, Afghanistan, and Xinjiang (Part 3), “As early as 1999, a Chinese academic specialist on Xinjiang … estimated that as many as 10,000 Uyghurs had travelled to Pakistan for religious schooling and ‘military training’. In May 2002, the Chinese government claimed that over 1,000 Uyghurs had been trained in Taliban camps”.10

Several events amid the turmoil of the 20th century in both China and the Soviet Union helped set the stage for a relatively small, but significant, number of ethnic Uyghurs—within Xinjiang or living in the Uyghur diaspora—to be pulled into the spreading radical jihad movement after Soviet forces left Afghanistan in 1989. These factors included:

• Cross-border population flows between Soviet Central Asia and Xinjiang, which borders Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Russia. In 1966-76, thousands of Uyghurs fled China to avoid the harsh domestic policies of the Great Cultural Revolution (GCR). The Uyghur population in Kazakhstan, which had been more than 50,000 a hundred years ago, ballooned to above 200,000. The Uyghur diaspora in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (the population of Tajikistan is not Turkic), as well as in Turkey, numbers tens of thousands in each country. In the other direction, so to speak, Central Asian ethnic groups are heavily represented in the population of Xinjiang; around 2 million Kazakhs live there, for example, despite the fact that Kazakhs, too, emigrated en masse from Xinjiang in the tumultuous 1930s and again during the GCR. The Uyghur diaspora became a platform for various types of agitation in and around Xinjiang.

• As Deng Xiaoping consolidated his power as China’s leader in and after 1978, he instituted an Open Door policy, under which many restrictions to both religious activity and foreign travel were relaxed. Beijing saw benefit in encouraging investment from the Middle East (again, this was in the decade of Saudi Arabia’s fabulous oil revenues), while it had a shortage of imams and religious teachers for China’s Muslims, among whom are not only Uyghurs, but also the just as numerous Chinese-speaking Hui Muslims.

It is also noteworthy that Chinese leaders did not perceive the Afghanistan mujaheddin as a problem for them in the 1980s. With the Sino-Soviet split still in effect, and armed clashes between China and the USSR only a decade in the past, Beijing cooperated with the United States during Operation Cyclone. Claudia Zanardi, an academic researcher, reported that Beijing “subsidised mules and US$200–400 million worth of weapons to the Mujahidin and the PLA [People’s Liberation Army—the Chinese military] had facilities in Peshawar and near the Pakistani border with Afghanistan where it employed 300 military advisers. In 1985, the PLA opened military camps in Xinjiang to train the Mujahidin with ‘Chinese weapons, explosives, combat tactics’, etc.”11

Largesse from none other than the Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation, the Saudi NGO soon to be banned by the UN, financed mosque construction, schools and scholarships in China in the 1990s. These programs increased the influence of Saudi-brand Salafism and Wahhabism among Chinese Muslims. These fundamentalist ideologies proliferated through Saudi NGOs and preachers who arrived in China, facilitated by a handful of the hundreds of Chinese people who had returned home after studying on scholarship at Saudi universities.12

Professor Rohan Gunaratna, a specialist at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, summed up the results 30 years later: “The ideological footprint of Salafism in China is growing. Salafism is an ideological spectrum from the peaceful to the violent. Like elsewhere in the world, the Muslims most susceptible to recruitment by extremist and terrorist groups are those who have embraced Salafism.… Although most Salafists in China are peaceful, increasingly the version of Salafism influencing a growing minority of Chinese is of both religious and security concern.”13

Gunaratna says that radical ideology in China is reinforced by an increasingly influential online version, “Cyber Salafism”: “Also called ‘cut and paste Islam’, Cyber Salafists selectively take passages out of context from religious texts and drive Jihadism and Takfirism, a departure from classical Salafism.”

Continuation next week: ‘Afghan’ jihadist terrorism comes to Xinjiang

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. Joe Stephens, David B Ottaway, “From US, the ABC’s of Jihad”, Washington Post, 23 Mar. 2002.

2. Ely Karmon, “Pakistan, the Radicalisation of the Jihadist Movement and the Challenge to China”, Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia), No. 3, 2009.

3. Glen Isherwood, “Who Is Sponsoring International Terrorism?”, March 2015 Citizens Electoral Council conference presentation, online at http://cec.cecaust.com.au/2015conference/.

4. Paul M.P. Bell, “Pakistan’s Madrassas—Weapons of Mass Instruction?”, Naval Postgraduate School thesis, March 2007, online at www.hsdl.org.

5. Ramtanu Maitra, “Foreign-Backed Taliban Armies Threaten Central Asia”, EIR, 8 Sept. 2000.

6. Yossef Bodansky, “The Great Game for Oil”, Defense and Foreign Affairs: Strategic Policy, June/July 2000.

7. See Note 5.

8. Ramtanu Maitra, “Look Who Created the Taliban”, EIR, 2 Oct. 2009.

9. Marvin Perry, Howard E. Negrin (eds.), The Theory and Practice of Islamic Terrorism: An Anthology (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

10. Graham E. Fuller, Jonathan N. Lipman, “Islam in Xinjiang”, in S. Frederick Starr, ed., Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland (Routledge, 2004).

11. Claudia Zanardi, “The Changing Security Dimension of China’s Relations with Xinjiang”, 31 Mar. 2019, online at www.e-ir.info, citing other academic studies.

12. Mohammed Al-Sudairi, “Chinese Salafism and the Saudi Connection”, The Diplomat (www.diplomat.com), 23 Oct. 2014.

13. Rohan Gunaratna, “Salafism in China and its Jihadist-Takfiri strains”, 18 Jan. 2018, online at www.mesbar.org. 2018. Takfiri are Muslims who accuse other Muslims of being infidels.