Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 4)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

Parts 1-3 of this series appeared in the AAS of 18 November and 2 and 9 December 2020. Our second and third articles recounted the “Arc of Crisis” policy of the 1970s-80s, which was the underpinning of US and British support for the mujaheddin guerrilla groups in Afghanistan, in their war against the Soviet forces that intervened there in 1979 and stayed until 1988. From among the tens of thousands of US- and UK-backed mujaheddin in Afghanistan came a core of radical Islamist terrorists, who formed the al-Qaeda and Islamic State (ISIS) terrorist organisations.

In Part 3 we cited an officer of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), who considered the Arc of Crisis approach a success, stating in 1999: “The policy of guiding the evolution of Islam and of helping them against our adversaries worked marvellously well in Afghanistan against the Russians. The same doctrines can still be used to destabilise what remains of Russian power, and especially to counter the Chinese influence in Central Asia.”

Two apostles of the Arc of Crisis doctrine highlighted in previous articles of this series were Bernard Lewis of British Army Intelligence, the University of London, and Princeton University, and Graham Fuller of the CIA, the State Department, and the Rand Corporation. Lewis was, and Fuller still is, an expert on Turkey. They were writing about modern Turkey and its predecessor state, the Ottoman Empire (1453-1922), even while concentrating on the Middle East and then Afghanistan in the 1970s-80s.

When the world’s power blocs and the political map of Eurasia shifted with the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, their attention turned to ways of keeping post-Soviet Russia weak and, slightly later on, of weakening China. Turkey-based organisations professing the ideology of Pan-Turkism (or Turanism, or the Pan-Turanian idea), a notion of uniting all Turkic language speakers into a single state, activated across central Eurasia with the encouragement of these Anglo-American intelligence specialists.

Fuller proclaimed in 1993 that “A huge Turkish belt has now revealed itself, stretching from the Balkans across Turkey, Iran, and Central Asia, up into the Russian heartland of Tatarstan and into western Siberia, deep into western China, and to the borders of Mongolia, comprising in all some 150 million people”, who he said were guided by “the concept of a shared sense of Turkishness”.1 That characterisation of Turkic ethnic populations implies the dismemberment not only of the USSR, but of Russia itself, and China and Iran—a prospect in line with the “one-empire” or “unipolar” world, which the so-called neoconservative grouping in Washington and London proclaimed at that time.

Bernard Lewis, who had been promoting Turkey’s rise as a major regional power since the 1960s, would tell a January 1996 conference of bankers in Ankara, Turkey’s capital, that there now existed a “vacuum in the region which Turkey should and must fill”.2

Some of the Pan-Turkist networks activated in the post-Soviet years had existed in dormant or semi-dormant form since the end of World War II, when British and American intelligence co-opted fighters from guerrilla groups, of various ethnicity, that had been allied with the Nazis. Their ideology of Pan-Turkism was rooted in the power games of the British Empire.

The 19th-century British Foreign Office’s fostering of “Pan-Turkic” and “Pan-Islamic” movements in Turkey had even older precedents, for the Ottoman Empire had been manipulated by outside oligarchical interests ever since its consolidation in the mid-15th century. The Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople (Istanbul), putting an end to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire (330-1453), thanks to Venice, the world’s financier centre of that time. Byzantium and Venice had been closely allied and interwoven for centuries, but the Venetian authorities ignored their pledge to defend Constantinople, and stood by as Sultan Mehmed II besieged and captured the city in 1453. The Venetians had their reasons, in the framework of wanting to disrupt the unification of the Roman and Eastern Christian churches, reached by the Council of Florence (1437-39) on a basis conducive to the development of the Renaissance and nation-states, which would challenge Venetian power. Venice did not, however, relinquish its influence and power in Istanbul; for centuries, the Ottoman Empire’s banking, intelligence and administrative apparatus—starting with the dragomans, or court interpreters—remained under the control of Greeks and others from Venice and the areas under its control.

The centuries-long relationship of foreign oligarchical operatives to Ottoman Turkey was well captured by Emmanuel Carasso, one of the organisers of the so-called Young Turk insurgency that took over the Ottoman Empire in 1908 and ran it during its final decade. As reported by British journalist Henry Wickham Steed, Carasso was asked at a meeting on the island of Prinkipo in 1913, when the Young Turks were up to their ears in the Balkans conflicts that would soon precipitate World War I, “what he and his like were going to do with Turkey.” Carasso replied, “Have you ever seen a baker knead dough? When you think of us and Turkey you must think of a baker and of his dough. We are the bakers and Turkey is the dough. The baker pulls it and pushes it, bangs it and slaps it, pounds it with his fists until he gets it to the right consistency for baking. That is what we are doing. We have had one revolution, then a counter-revolution, then another revolution and we shall probably have several more until we have got the dough just right.”3

The Young Turks

In the 19th century, the “Young X” movements of reformers and revolutionaries, starting with Giuseppe Mazzini’s Young Italy in the 1830s, enjoyed the patronage of the British Foreign Office and other London circles, for whom they served as useful tools to destabilise the continental European powers or set them against each other. Lord Palmerston, in charge of the Foreign Office for most of the time from 1830 to 1851, much appreciated the London-based Mazzini and his projects. The “Young X” groups, typically, aimed to build up an identity based on ethnicity and territorial aspirations (“blood and soil”). Their complaints against the continental monarchies may often have included legitimate ones, but above all they were pawns in British geopolitics.

The Young Ottomans first appeared in 1865 in Paris, soon to ally with Mazzini’s European Revolutionary Committee. By this time the Ottoman Empire, in decline, was known as the Sick Man of Europe. The group achieved a short-lived success with Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s adoption of a constitution in 1876, only for him to restore absolute rule and drive the Young Ottomans underground the next year.4

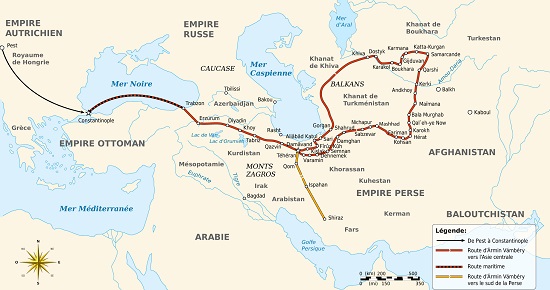

Throughout the last third of the 19th century, a Hungarian Turcologist named Arminius Vambery, on hire to the British Foreign Office, campaigned for Eurasia-wide Turkic solidarity. Vambery briefed Lord Palmerston, during the latter’s last prime ministership and near the end of his life, on the “collision between England and Russia in the distant East”.5 Vambery had just completed a three-year (1861-64) tour of Turkey, Iran and Central Asia, the territory of the Great Game of Eurasian geopolitics (Part 1). He received honours for his work from the Austrian Emperor and, in 1902, from King Edward VII of England, who hailed his services to England.

Vambery advocated a Polish-Hungarian-Ottoman alliance against Russia (Hungary being part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while Poland was divided between Austria and Russia). A subsumed scheme was that the entire multiethnic Ottoman Empire, including Arabs, Armenians, and various Slavic peoples, should consolidate around a Turkish chauvinist identity, to which the Turkic peoples of Central Asia should also be recruited. This was Pan-Turkism. In 1869 the Young Ottoman newspaper Hurriyet (Liberty) fell into line with Vambery’s idea, criticising the Ottoman Empire’s leaders for failure to defend the Islamic Turkic peoples of Central Asia. (These Central Asians spoke Turkic languages, but had never been under Ottoman rule.)

After the Young Ottomans, two decades later, came the Young Turks, who seized power in the Ottoman Empire in 1908, keeping the Sultan on as a figurehead. Key leadership for the Young Turks came from the above-mentioned Carasso, with backing from his friends like Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata, the Venetian financier and political operator who would later become Mussolini’s finance minister.

Also on the scene in Constantinople as the Young Turks movement took shape was Aubrey Herbert, a British aristocrat and intelligence officer. A member of London committees campaigning for the rights of various national entities in the Balkans, Herbert held that “democratic rule” by the Young Turks was the best hope for his beloved Albania (Herbert at one point was offered the throne of Albania).6 The hero of John Buchan’s 1916 novel Greenmantle, a British spy aiding the Young Turks, was modelled on Herbert. T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”) identified Herbert as the actual head of the Young Turk insurrection.7

The Young Turks launched a policy of “Turkification” of the Empire. Within a few years, the resistance they provoked from Slavic and other provinces touched off the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, which, in turn, served as the short fuse by which World War I was ignited.

Central Asia between the Wars

People who grew up during or after the four decades of the Cold War (c. 1950-90) internalised a notion of East and West, hermetically sealed off from each other by Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” for that entire time, and even earlier—ever since the Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917. That picture of the world is misleading, since in reality there was a constant intersection of political processes and institutions inside and outside the Soviet Union. Since the Russian Revolutions (one in 1905 and two in 1917) themselves had been heavily manipulated by British Intelligence, in particular, even some of the institutions of the new Soviet state were organised by Russian revolutionaries who would work with whatever foreign intelligence agency they found it convenient to do so at a given moment, or even by foreigners directly. The founding of Soviet military intelligence (the future GRU) in 1918 by British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) Captain George Hill, then acting as an aide to Bolshevik War Commissar Leon Trotsky, is an outstanding case.

The implications of such relationships were immense in Central Asia, the scene of constantly shifting borders, power alignments, and intelligence agency attempts from all sides to gain the upper hand.

The Young Turks began to split already during the Balkan Wars. Under Enver Pasha as Minister of War, the Young Turk government brought the tottering Ottoman Empire into World War I on the side of Germany, a move Enver saw as an opportunity to wage Pan-Turkist offensives into areas east of Ottoman territory. His campaign through eastern Turkey towards the Caucasus Mountains and Armenia in 1914 ended in disaster at the Battle of Sarikamish, when tens of thousands of Turkish soldiers froze to death in the mountain snows.

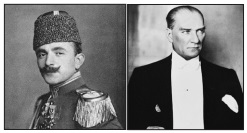

Enver nonetheless went ahead to form an Islamic Army of the Caucasus in 1918—already after the Bolsheviks had taken power—in hopes of seizing southern Russia. When the Ottomans capitulated to the Allies in October 1918 (Russia had already withdrawn from the war), Enver was fired and fled to Germany. The other main faction of the Young Turks, a nationalist but not Pan-Turkist tendency led by Mustapha Kemal Ataturk, waged a war of resistance against the Anglo-French occupation, culminating in creation of the Republic of Turkey under his leadership in 1923. Ataturk and his “Kemalists” came to embody a nationalist, but secular and non-expansionist model for modern Turkey. He was its President until his death in 1938.

While in Germany, Enver Pasha sought allies (or useful tools) for his Pan-Turkic vision. One of these was Karl Radek, a Bolshevik figure with an unparalleled record of hob-knobbing with foreign intelligence agencies, who in 1923 would propose to ally with the young Nazi Party against France’s occupation of Germany’s industrial Ruhr region. In 1919-20, Radek was imprisoned in Germany. As some in Berlin toyed with conjuring up an alliance of countries wounded by the British and French in the war—Germany, Russia and Turkey—Radek was allowed a visit from Enver Pasha. Upon Radek’s release from jail, he returned to Moscow and promptly was assigned as secretary of the newly formed Communist International, or “Comintern”.

One of Radek’s first projects was to organise the Congress of Peoples of the East, held in Baku, Soviet Azerbaijan in September 1920. With the failure of the working class to rise up in a revolution in Germany, Lenin and the Bolsheviks had proclaimed the need for anti-imperialist struggle across Eurasia. The Baku conference keynote speaker, Georgi Zinoviev, thundered out an appeal for Islamic jihad, Holy War, against the imperialist oppressors. The 1,800 delegates were representatives of political groups (and foreign intelligence agencies) from all over the world, among them Enver Pasha.

Of course, the Soviets had in mind an anti-imperialist struggle against British colonies, not the areas the Russian Empire itself had subsumed during the 19th century. Initially, Moscow kept Central Asia organised as a single Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Turkestan, using the name Central Asia had acquired under the Tsarist regime. Only in 1924 did Moscow shift to an administrative division of the region into separate, ethnically defined republics: Kazakhstan, Kirghizia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This line of Soviet thinking, marked by the influence of Mazzini’s model, became known as “Stalin’s nationalities policy”; it set the stage for troublesome incidents of ethnic separatism in the USSR’s and Russia’s future.

In 1921 Enver Pasha offered his services to Lenin, to drive into Turkestan and suppress the basmachi (“bandit”) movement that had been fighting against the Red Army in Central Asia in the just-ended Russian Civil War. Then, Enver promised, he would establish a Muslim Republic of Turkestan and break through to India to touch off an insurrection against British power there.

Enver Pasha proceeded into Central Asia, but joined the basmachi instead of suppressing them. He was killed by the Red Army in August 1922, near modern Dushanbe, Tajikistan.8

British Intelligence had its own agents in post-World War I Central Asia, monitoring and meddling in these processes. Lt. Col. P.T. Etherton was posted at Kashgar (western Xinjiang) as “British Consul-General and Political Resident in Chinese Turkistan”, 1918-24, observing and reporting on the course of the Russian Civil War in Central Asia. He also “co-operated with the anti-Soviet Basmachi guerrillas in Western Turkestan while working to limit the spread of Soviet influence in southern [Xinjiang]”.9

Rule over Xinjiang itself was in flux between the wars. The Chinese province’s governor from 1907 to 1928 (bridging the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912), based at Urumqi in northern Xinjiang, was a Han Chinese named Yang Zengxin, who was knowledgeable about Islam and had strong connections with Turkic ethnic families in the region. Recipient of an honorary British knighthood from the British Indian Government, Governor Yang waged cautious diplomacy with Soviet representatives who would show up in Xinjiang; he sought chiefly to keep defeated White Army forces from fleeing into the province with the Red Army in pursuit.

Greater turmoil in Xinjiang followed the assassination of Yang in 1928, as warlords and rival Sufi brotherhoods clashed. In November 1933 one Sabit Damolla proclaimed the short-lived Turkish-Islamic Republic of East Turkestan (TIRET), based in the far west at Kashgar. It lasted until May 1934. J.W. Thomson-Glover, the contemporary British Consul-General in Kashgar, noted that one of TIRET’s five fundamental policies was “To seek friendly relations with the British Government and to obtain its aid as far as was possible”.10 Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Republic of China’s Kuomintang government, believed that Britain was behind TIRET as a separatist project against China. Just two years earlier, in 1931, Britain had looked on without lifting a finger, when Japan invaded Manchuria, at the other end of China.

Sheng Shicai, a Han warlord who governed Xinjiang after the collapse of TIRET, was more amiable in relations with the Soviets, setting the stage for a second “East Turkestan Republic” (1944-49), situated in the north by the Soviet borders and enjoying Soviet support.

Nazi Germany sought to build its own presence in Central Asia and Xinjiang. When the war broke out, Nazi leaders ordered the formation of a Turkistanische Legion, comprised of Red Army POWs of Central Asian ethnicities, captured during Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. One of its organisers was Nuri Killigil, a Pan-Turkist former Ottoman general, who happened to be a younger half-brother of Enver Pasha. The Turkestan Legion was deployed primarily in Italy. Several of its veterans were to play an important role in interaction with Anglo-American intelligence agencies after the war.

The ‘Gladio’ template

A document titled “The Pan-Turanian Idea” was filed in the CIA’s archives in 1948, the first year of the Agency’s existence, and declassified only in 2005, after fifty years of secrecy.11 A dissertation by an unnamed German Turkish expert, the paper discussed the Nazis’ desire to establish contact networks and alliances in the Turkic areas of Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Balkans, motivated by a plan to dissolve the Soviet Union and replace it with a Pan-Turkic federation, loyal to the Nazis. It asserted that Turanism “remain[ed] alive among all Turkic peoples. The small number of active advocates … would, if permitted free activity, be of a surity [sic] able to convert the majority of the population for a union of all Turkic states.” The document includes a “Map of Projected Federation of Turanian States”, stretching from Turkey to Outer Mongolia, which included “East Turkestan”—China’s Xinjiang.

Such close attention to abandoned Nazi schemes was typical of British Intelligence and the (future) CIA after World War II, and it extended to personnel. Allen Dulles, the future first CIA head, made a deal with SS Gen. Karl Wolff at the end of the war, “to recycle Nazi and Fascist networks into post-war military and intelligence structures.” These came to be called “stay-behind” networks, not because they were Nazi leftovers, but because scenarios called for them to conduct operations under Soviet occupation, were the Soviet Union to invade Western Europe, on the model of British Special Operations Executive (SOE) guerrilla warfare in Nazi-occupied Europe.12

The classic version of this plan was “Operation Gladio” in Italy, whose existence was exposed in 1990, when Italian parliamentarians revealed that the network had been responsible for the horrific terrorist attacks and assassinations that ravaged Italy in the 1970s. That period was known as “The Strategy of Tension”.13

Coinciding with the height of Gladio’s activity in Italy, Turkey in the 1970s was rocked by terrorism at the hands of an organisation called the Grey Wolves. This was, together with the military institutions protecting it, essentially the Turkish arm of Gladio. It was the paramilitary branch of the Nationalist Movement (or “Action”) Party (Turkish acronym MHP) and operated under the protection of Counter-Guerrilla, a section of the Turkish Army’s Special Warfare Department, set up in collaboration with the CIA.14

Alparslan Turkes and the Grey Wolves

Col. Alparslan Turkes (1917-97) founded the MHP in 1969, on the base of the Republican Villagers Nation Party, which he had joined in 1965. MHP’s Grey Wolves arm also dates from the late 1960s. By that time, former Nazi-sympathiser Turkes had been an agent of influence of the Cold War-era USA for two decades. The roots of both Turkes and the Grey Wolves run back to before World War II.

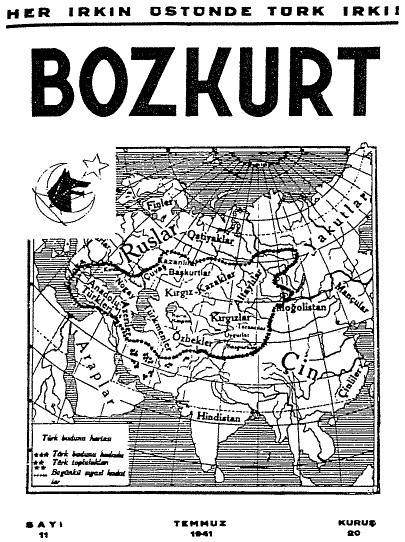

The young Turkes admired racist Pan-Turanian adversaries of the Kemalist state in 1930s Turkey. He especially favoured Huseyin Nihal Atsiz (1905-75), who published Orhun: A Pan-Turk Journal in 1933-34 and again in the late 1940s, featuring articles on particular areas that should be part of a single “Turkish” state, like Azerbaijan and East Turkestan (Xinjiang). “All of Turkestan and all the Turkish lands are ours!” he proclaimed, alongside theories of “racial unity” based on purity of blood.

Reha Oguz Turkkan, a younger Pan-Turanian who was a great-nephew of Fakhri Pasha, the last Ottoman Commander of the Army, used “grey wolf” imagery as Pan-Turkist symbolism in his journals Ergenekon (1938; named for a mythical Turkic homeland in the Altay Mountains of southern Siberia, Kazakhstan and Mongolia) and its 1939-42 successor, called explicitly Bozkurt (Grey Wolf). Turkkan’s magazines featured the slogan, “The Turkish race above every other race”.15 The Pan-Turkist writer and publisher Atsiz took up the “grey wolves” theme in a popular trilogy of post-war novels. Death of the Grey Wolves (1946) was the tale of a failed attempt by a 7th-century Turkic prince to kidnap an Emperor of China. This was followed by The Grey Wolves Return to Life and Mad Wolf.

In the meantime, Atsiz agitated at the end of the war against any cooperation with the Soviet Union, which was about to defeat the Nazis. In 1944, after fomenting large anti-Communist demonstrations, he was arrested on charges of plotting “to overthrow the government in order to form a state based on racist and Turanist principles.”16 Rounded up with him, jailed and court-martialled was the young Army Capt. Alparslan Turkes. President Ismet Inonu, who had succeeded Kemal Ataturk in 1938, denounced the conspirators: “We are Turkish nationalists, but we are the enemy of the principle of racism in our country… The idea of Turanism is also a harmful and diseased phenomenon of recent times”.

Several Turkish authors have described Turkes as an admirer of the Nazis with a network of Nazi contacts, although the Pan-Turanists had their own viciously racist doctrines without having to borrow them from German fascists.

With the death of President Franklin Roosevelt in 1945 and the proclamation of the Truman Doctrine in 1947, whereby President Harry Truman committed the USA to confrontation with its wartime ally the Soviet Union, Turkey quickly occupied a central place in the Cold War. Denial to the Soviets of free passage through the Turkish Straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean was an issue by 1946. In 1951, Greece and Turkey were cleared for membership in NATO, the new Atlantic alliance directed against the USSR.

Now that the Soviet Union was defined as an adversary, Turkish anti-Communist detainees like Turkes were released from prison. In 1947, military cooperation with the USA began, some of it kept secret. In 1948, Turkes was one of 16 Turkish officers sent for military training in America. He completed further officer training back home, graduating from the Turkish Military Academy in 1955. He then served in various capacities, including as a member of the Turkish General Staff delegation to the NATO Standing Group in Washington.

Turkes co-organised and was spokesman for a violent military coup in 1960. His radio-broadcast speech announcing the takeover emphasised that Turkey’s commitment to NATO would not change. He then fell out with fellow junta members on the issue of returning power to a civilian government (he was against it), and was banished to a diplomatic posting in India, returning to Turkey in 1963 to launch a new political career. By 1969 he had founded the MHP, based on his racist Pan-Turkist beliefs now of 30 years’ standing. In 1981 it was described by the New York Times (accurately, for once) as a “xenophobic, fanatical nationalist, neofascist network steeped in violence”.

One project of that first delegation of Turkish trainees in the USA had been to set up a unit called the Tactical Mobilisation Group, which was succeeded in 1965 by the Special Warfare Department and in 1992 by a Special Forces Command. Counter-Guerrilla was subordinate to these agencies, and the Grey Wolves operated under the wing of Counter-Guerrilla.

In the late 1970s, Grey Wolves death squads launched urban guerrilla warfare, committing terror attacks and shootings in a campaign against leftists. Civilians and public officials were among the approximately 6,000 people killed.17 In 2008 the Turkish news agency Zaman reported that Grey Wolves documents, submitted in a court case, showed that Turkey’s National Intelligence Organisation (MIT) had paid regular salaries to Grey Wolves operatives carrying out illegal operations, including violence and political assassinations. Former Turkish Supreme Court Justice Emin Deger opined in the late 1970s, that there was a close working connection between the Grey Wolves, Turkish intelligence, the Turkish military’s Counter-Guerrilla, and the CIA.18

The Grey Wolves achieved international notoriety in 1981, when its member Mehmet Ali Agca tried to assassinate Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square. Estimates of Grey Wolves membership ranged as high as 200,000 registered members and one million supporters, at its peak around 1980.

Post-Soviet Pan-Turk revival

Active as the Pan-Turkists had been on the Turkish political scene since World War II, they and their international support networks went into overdrive when the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991.

In May 1992, a New York conference of the World Turkic Congress heralded the idea of a revival of a “neo-Ottoman” or Pan-Turkic empire. Two hundred participants, including representatives from Turkey, Central Asia and Xinjiang, heard speeches by Heath Lowry, the successor to Bernard Lewis as the premier Turcologist at Princeton University, and Lowry’s own mentor, Justin McCarthy of the University of Kentucky. McCarthy gave a keynote straight out of Lord Palmerston’s propaganda handbook from 130 years earlier, claiming that Turkey and Turkic peoples must be avenged against Russia for inflicting massacres and genocide against them. A map of the projected Empire of “Turkestan”, handed out at the conference, encompassed all of Central Asia and Xinjiang Province, renamed on the map as “Uighuristan”.

Additional international organisations advocating the mobilisation of Turkic peoples again Russia were formed in the 1989-91 period of break-up of the Soviet bloc:

The Quincentennial Foundation, inaugurated in 1989 in Istanbul, held a gala in April 1992 in New York, to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Ottoman Empire’s acceptance of Jews who had fled Spain. Its organiser, Steve Shalom, from a prominent Ottoman family, said that the Foundation’s goal was to foster a strategic deal between Turkey and Israel against common enemies in Eurasia. Quincentennial was founded by Jak Kamhi, a wealthy electronics industrialist who had a business partnership with Tugrul Turkes, son of Alparslan.19

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) was founded in 1991 by Lord Ennals, a former UK Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and activist for Tibetan independence from China, and Dutch international lawyer Michael van Walt van Praag. The UNPO promptly launched support missions to separatists in the Russian North Caucasus. By 1995, its list of 43 “peoples” who needed more representation included the Uyghurs of “East Turkestan”, as Xinjiang Province was labelled on UNPO maps. The UNPO’s inaugural president was Erkin Alptekin, son of the Uyghur separatist Isa Yusuf Alptekin.20

In December 1992, the first East Turkestan World National Congress convened in Istanbul, chaired by Isa Yusuf Alptekin himself. He declared that the dissolution of the Soviet Union indicated that “the time for collapse and dissolution has arrived for the Chinese empire. We expect help from our beloved Turkey, our new republics [in former Soviet Central Asia], co-religionists, and mankind in general, to put a check on China.” Alptekin’s remarks met with enthusiasm from Turkish government representatives. The Grey Wolves leader, Alparslan Turkes, attended, telling the audience that “Chinese imperialism’s repression of East Turkestan must not be tolerated.”21

In the years 1992-2004, at least eight international congresses, associations, and governments-in-exile were established in pursuit of East Turkestan or Uyghur independence from China. Fifteen or more underground radical organisations, some of them violent, came into being in approximately the same years; they will be discussed in our next articles, in conjunction with the “Islamisation” of East

Turkestan separatism.

Alptekin had maintained ties with Turkes for many years. The website of the World Uyghur Congress, formed in 2004 as a successor to the 1992 conference’s efforts, continues to celebrate Turkes and promote endorsements of East Turke-stan separatism by current leaders of Turkes’s MHP party and the Grey Wolves.22 A 2017 article reposted by the WUC described Turkes as the “immortal leader of the MHP and the Nationalists”, “the legendary leader … who want[ed] to stop the Chinese immigration to East Turkistan”. The article claims that “East Turkistan” (Xinjiang) is part of the Turkic world—the “bleeding wound of Turkishness”.

Next: Islamisation of the “East Turkestan” campaign

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. Graham E. Fuller, “Conclusions: The Growing Role of Turkey in the World”, in Turkey’s New Geopolitics: From the Balkans to Western China (Westview Press, 1993). A co-author of this Rand Corporation study was Paul Henze, who had been the National Security Council notetaker at a key meeting of CIA and State Department officials with National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski in October 1979 (Part 2 of this series), on escalating military aid to mujaheddin fighters in Afghanistan as an anti-Soviet force.

2. Joseph Brewda, “The neo-Ottoman trap for Turkey”, EIR, 12 Apr. 1996.

3. Henry Wickham Steed, Through Thirty Years, 1892-1922 (Doubleday, 1924). That future Times of London editor Steed, a notorious anti-Semite, was rubbing elbows with Carasso, a member of the Donmeh community, shows how geopolitical priorities make strange bedfellows. The Donmeh (“converts”) were descendants of Jews who had fled into the Ottoman Empire upon expulsion from Spain in the 1490s; in the 17th century many became followers of Sabbatai Zevi, a Jewish mystic, and created a syncretic belief system out of Zevi’s kabbalism and Islamic Sufi mysticism. Several leaders of the Young Turks’ core group, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), were Donmeh from Carasso’s hometown of Salonica in Ottoman Macedonia (modern Thessaloniki, Greece). Carasso was also grandmaster of the Macedonia Risorta (Macedonia Resurrected) freemasonic lodge of Salonica, which was under the wing of the powerful Grande Oriente d’Italia (Grand Orient of Italy) lodge.

4. Joseph Brewda, “David Urquhart’s Ottoman legions”, EIR, 12 April 1996.

5. Arminius Vámbéry, His Life And Adventures Written by Himself (T. Fisher Unwin, 1889).

6. Daut Dauti, “Britain, the Albanian Question and the Demise of the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1914”, University of Leeds dissertation, 2018.

7. Jeffrey Steinberg, Allen Douglas, Rachel Douglas, “Cheney Revives Parvus ‘Permanent War’ Madness”, EIR, 23 Sept. 2005.

8. Peter Hopkirk, Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin’s Dream of an Empire in Asia (John Murray, 1984) relates the post-World War I conflicts in Central Asia highlighted in the preceding four paragraphs.

9. Andrew Forbes, Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang, 1911-1949 (Cambridge U. Press, 1986).

10. Ibid.

11. The Pan-Turanian Idea, 1948.

12. Claudio Celani, “Swiss Think-Tank Exposes ’NATO’s Secret Army’”, EIR, 7 Jan. 2005.

13. Claudio Celani, “Strategy of Tension: The Case of Italy”, EIR, 2004.

14. Daniele Ganser, NATO’s Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe (London: Frank Cass, 2005).

15. Jacob M. Landau, Pan Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation (Indiana U. Press, 1995) chronicles the publications mentioned here.

16. Umut Özkirimli, Spyros A. Sofos, Tormented by History: Nationalism in Greece and Turkey (Columbia U. Press, 2008).

17. “Turkey: Nation and tribe the winners”, The Economist, 22 April 1999.

18. Joost Jongerden, The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds (Brill, 2007).

19. Brewda, “Neo-Ottoman trap…” (Note 1) includes eyewitness accounts of the 1992 New York conferences.

20. Mark Burdman, “UNPO plans key role in Transcaucasus blowup”, EIR, 12 Apr. 1996.

21. Joseph Brewda, “Pan-Turks target China’s Xinjiang”, EIR, 12 Apr. 1996.

22. Ajit Singh, “Inside the World Uyghur Congress: The US-backed right-wing regime-change network seeking the ‘fall of China’”, The Grayzone, 5 Mar. 2020.