Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 8)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

Parts 1–7 of this series appeared in the AAS of 18 November, 2 and 9 December 2020; 20 January, 3 and 17 February, and 17 March 2021. References to those instalments, and to subtitled sections within them, are given in parentheses in this concluding article.

After the USSR

All the forces identified in this series of articles became more active after the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. There was a struggle for control of Central Asia’s subsoil resources, and, above all, a push by Anglo-American strategists of the geopolitics tradition (Part 1, “The Great Game and Mackinder’s ‘Heartland’”) to prevent either Russia or China from dominating the region. Under the Wolfowitz Doctrine (Part 3), which said that no country must ever attain as much power as the Soviet Union had possessed, Russia was the initial target of covert destabilisation operations; causing trouble for China became a priority as Beijing began its serious economic rise and launched development of the transcontinental New Silk Road in the late 1990s (Part 3, “Xinjiang becomes a target”).

The activated elements were several.

Outright terrorism. The radical jihadists backed by the USA and UK against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, 1979-88, expanded into a broader movement, generating al-Qaeda and ISIS and affecting dozens of countries (Part 2, “Operation Cyclone—Afghan Mujaheddin”; Part 3, “Mujaheddin fan out”). As we have seen, Uyghur radicals were ultimately recruited into these networks in significant numbers (Parts 5 and 6).

Pan-Turkism. Radical Pan-Turkists from Turkey, who have been a bulwark for Uyghur separatism, also blended together with the internationalised mujaheddin. There had been Turkish fighters in Afghanistan in the 1980s, and their presence in Afghanistan and Pakistan in subsequent decades has been plentifully documented.1 The militant Turkish nationalists’ paramilitary arm, the Grey Wolves, with Afghanistan veterans among them, became major players in the trafficking of Afghan heroin as it surged in the 1990s. On the political level, the Pan-Turkist figures who had been active in Turkey and elsewhere in the post-World War II period, including on behalf of the US CIA (Part 7, “The CIA’s Captive Nations”), moved to boost their activity in Russia’s North Caucasus region and the newly independent countries of Central Asia.

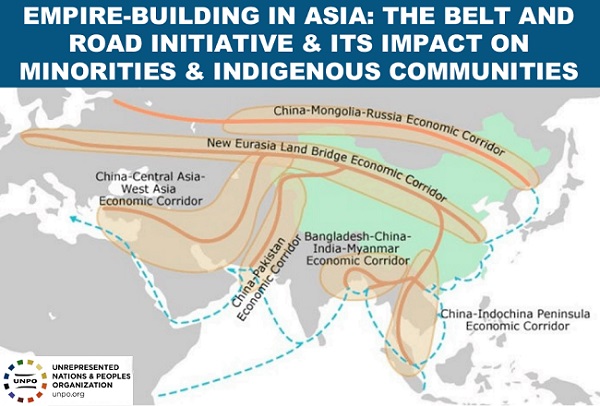

Special-purpose branches of “Project Democracy” (Part 7, “Project Democracy”). Alongside major institutions such as the US National Endowment for Democracy, affiliated projects were launched that are of particular importance for Xinjiang. Those are the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) (Part 4, “Post-Soviet Pan-Turk revival”) and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, which has roots in the Captive Nations groups of the 1950s and later.

Uyghur diaspora. The second and third elements, Pan-Turkism and the specialised Project Democracy institutions, combined in efforts to organise the ethnic Uyghur diaspora into an effective lobbying force. Because it, and they, make up the platform for international agitation related to both Uyghur human rights in Xinjiang and separatism favouring a split-off of Xinjiang from China, we will discuss them further here, before surveying the main Uyghur and “East Turkistan” diaspora groups.

Pan-Turk inroads in Central Asia

The Pan-Turkist Turkish National Intelligence Organisation (MIT) friends of Ruzi Nazar, the Uzbek ethnic CIA officer who for decades had promoted an independent “Turkistan” in Central Asia (Part 4, “Alparslan Turkes and the Grey Wolves”; Part 7, “The CIA’s Captive Nations”), had laid groundwork in Soviet Central Asia long before the USSR disintegrated. Nazar’s acolyte and ex-MIT officer Enver Altayli, in his biography of Nazar, reports that MIT boss (in 1966-71) Fuat Dogu had “launched operations against the Soviet Union”, putting Turkey’s “valuable stock of experience … of subversive and conspiracy-based work inside the borders of the Soviet Union” at the disposal of the United States.2 Already in the late 1960s, Dogu and Nazar organised a secret conference near Istanbul, with attendance “from almost every region of the Turkic world, both from within the Soviet Union and outside it”, to study Soviet vulnerabilities on the “nationalities question”—the status of ethnic minorities. Dogu, according to Altayli, believed that most of the USSR’s natural resources lay in Turkic lands, and that “the destruction of the Soviet Union would only be possible when these lands broke away from it, and that was what one must work for.” Dogu arranged for Nesrin Sipahi, a famous singer of Turkish popular music, to concertise in Baku and Tashkent, which “made the Soviets uncomfortable”.

In May 1992 Ruzi Nazar visited now-independent Uzbekistan, his birthplace. Hundreds of people greeted him at the Tashkent airport. He met with President Islam Karimov, the former Communist Party chief in Soviet Uzbekistan. Nazar was then already 75 years old (he lived to be 98, dying in 2015), but his follower Altayli shortly thereafter was reported in the Turkish press to be acting as “chief advisor” to Karimov. Aydinlik, a Kemalist newspaper opposed to the Pan-Turkists (Part 4, “Central Asia between the Wars”), identified him as not only an MIT officer, but “former chief inspector of the National Movement Party” (MHP) of Pan-Turkist Alparslan Turkes, adding that he was using “MHP militants as a strike force”—that is, the Grey Wolves—and had also begun covert operations in Chechnya, across the Caspian Sea from Uzbekistan in Russia’s North Caucasus.3 Whether or not every detail of the 1993 Turkish media reports is true, the Pan-Turkists in Turkey surely thought that their time had come.

In those years there was a huge expansion of the network of schools run by the Fethullah Gulen movement into the Central Asian countries, becoming a conveyor for ideas from Turkey and influence from Gulen’s CIA friends.4

Cadre of the Turkish Grey Wolves and its youth branch Nizami Alem (“Universal Order” in Arabic) fought on the side of Turkic Azerbaijan against Armenia in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-94). They fought on the side of UK-backed Chechen separatists against Russia in the First and Second Chechen Wars, 1994 and 1999.5 Turkish sources indicated in 1996 that around 1,000 Turkish Nizami Alem fighters were involved in mercenary and volunteer operations in Chechnya, Azerbaijan, Iran, and alongside NATO’s Implementation Force (IFOR) in Bosnia.6 In 2000 CNN reported estimates that another 3,000-5,000 foreign mujaheddin based in Turkey were ready to pour into Chechnya.

The Pan-Turkist movement set up shop across Central Asia. When then-Prime Minister Li Peng of China toured the region in April 1994 to discuss economic cooperation, leader of the Kazakhstan-based United Revolutionary Front of East Turkistan Yusupbek Muglisi (Mukhlis) told journalists there, “We have decided to use all possible means, including terrorism, to bring about revolution in Xinjiang.” Muglisi was a Uyghur who had fled Xinjiang for Kazakhstan in 1960. He was later to meet with State Department officials in 1996, and announced an “armed campaign” against China in 1997.7

A Grey Wolves-linked journalist who frequented Central Asia remarked at that time, “We are now using Kyrgyzstan as a base for operations in Xinjiang, just as we used Turkey as a base for operations in the Caucasus”.8

Abulfaz Elchibey, a former Soviet dissident who openly espoused Pan-Turkism, was elected president of Azerbaijan in 1992. His accomplishments included bringing Azerbaijan into the International Monetary Fund and escalating its war with Armenia. Alparslan Turkes visited President Elchibey and supplied him with Grey Wolves paramilitary security units. Elchibey was ousted in 1993 amid disasters in the war. In 1995 a group of officers attempted to reinstate him, in an event dubbed the “Turkish Coup” in Baku, because of the widespread belief that the MHP and Grey Wolves were behind it; then-PM of Turkey Suleiman Demirel got wind of the plot and forestalled it with warnings to Azerbaijan’s leaders.

The Central Asia-oriented Pan-Turkist networks turned up in force, alongside Uyghurs, at the first East Turkestan World National Congress, held in Istanbul in December 1992. One of its organisers was Gen. Mehmet Riza Bekin, a Uyghur officer in the Turkish Armed Forces. He was the nephew of Meh-met Emin Bugra, a leader of the short-lived East Turkistan Republic in Kashgar in 1933 (Part 4, “Central Asia between the Wars”). Bugra left Xinjiang with Isa Yusuf Alptekin in 1949 and worked with him until his (Bugra’s) death in 1965. Bekin emigrated from Xinjiang with his family as a child in 1934, first to Afghanistan and onwards to Turkey, where he received a high-level military education. He served as an artillery officer in the Korean War, followed by various postings abroad, including in 1973 as a staff officer for military planning at the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO), a Cold War (1955-79) alliance of Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and the UK. Bekin retired from the military in 1977, at the age of 52, as a brigadier general,9 to concentrate on Uyghur issues. The paucity of detail about his overseas military postings lends credibility to the assertion by Turkish investigative journalist Soner Yalcin, in a biography of Turkish political figure Necmettin Erbakan, that Bekin was an operative of the MIT—a colleague of Dogu and Turkes.10

Uyghurs and Pan-Turkists alike, at the December 1992 Istanbul event and in declarations after the death of Uyghur activist Isa Yusuf Alptekin in 1995, went over the top with enthusiastic projections of a triumph of “Turkistan” in Central Asia, against both Russia and China.

Isa Yusuf Alptekin, chairman of the Congress and long-time associate of MHP and Grey Wolves leader Turkes (Part 4, “Post-Soviet Pan-Turk revival”): “The time for collapse and dissolution has arrived for the Chinese empire. We expect help from our beloved Turkey, our new republics [in former Soviet Central Asia], co-religionists, and mankind in general, to put a check on China.”

Alparslan Turkes: “Chinese imperialism’s repression of East Turkestan must not be tolerated.”11

Erkin Alptekin, Isa’s son, at his father’s funeral in 1995: “Ten years ago no one believed that the USSR would fall apart.Now you can see that. Many Turkic countries have their freedom now. Today the same situation applies to China. We believe in the not too distant future we will see the fall of China and the independence of East Turkestan.”12

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then-mayor of Istanbul and now president of Turkey, dedicating a park to the senior Alptekin in 1995: “Eastern Turkestan is not only the home of the Turkic peoples but also the cradle of Turkic history, civilisation and culture. To forget that would lead to the ignorance of our own history, civilisation and culture. The martyrs of Eastern Turkestan are our martyrs”.13

Special-purpose NGOs

We have written previously (Part 4) about the 1991 founding of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO), initiated by British and Dutch politicians. Its first support missions were for separatists in the Russian North Caucasus, but there was an early and constant emphasis on the Uyghurs of “East Turkestan”. As the UNPO’s first president, Erkin Alptekin gained a rostrum for preaching his Pan-Turkist ideas. The younger Alptekin was a veteran of CIA officer Ruzi Nazar’s Central Asia group at Radio Liberty in Munich (Part 4, “The CIA’s Captive Nations”), and had already made a contribution to the Pan-Turkist cause with the publication of a book in Turkish, The Uyghur Turks, in 1978.14

Since 2009, the UNPO has conducted joint seminars on Uyghur issues with the NED.

Additional institutional support for East Turkistan separatism came with the formation of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VCMF) in 1993. Even more so than the NED itself, this NGO was a direct spin-off from the CIA’s Captive Nations projects of the 1950s. Co-chairs of the National Captive Nations Committee, founded in 1959, were two Ukrainians: Lev Dobriansky and pro-Nazi Banderite Yaroslav Stetsko, Ruzi Nazar’s old friend and colleague from the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (Part 4). Dobriansky launched the VCMF, with Arc of Crisis orchestrator Zbigniew Brzezinski (Part 2) on its board.

Today the VCMF is the home base of Adrian Zenz (Part 7, “Intelligence agencies manipulate diasporas”), a leading fabricator of false or exaggerated accounts of Chinese policies in Xinjiang.

The World Uyghur Congress

The 1992 Uyghur conference in Istanbul, with 70 delegates from 14 countries, did not immediately produce a standing institution, but its participants engaged in building organisations throughout that decade. Australia-based Uyghur activist Ahmet Igamberdi, who was elected chairman of a “council” the meeting tried to establish, founded the East Turkistan Australian Association (ETAA) that same year. Erkin Alptekin, from his base at CIA-founded and still US government-funded Radio Liberty in Munich, had already in 1990 founded the East Turkistan Union in Europe (ETUE), the first “East Turkistan” organisation outside Turkey. The ETUE soon spun off the East Turkistan Cultural and Social Association (ETCSA) and an East Turkistan Information Centre (ETIC), both also initially based in Munich. A World Uyghur Youth Congress (WUYC) was established in Munich in November 1996, headed by Dolkun Isa, a former Chinese student activist who had left China in 1994.15

In 1998 an East Turkistan National Centre (ETNC) was formed in Istanbul, at a conference this time with 300 delegates from 18 countries. Its head was Gen. Bekin, and its offices were “on loan” from the Turkish government16—headed at that time by leaders of the deceased former President Turgut Ozal’s Motherland Party, under President Suleiman Demirel. Ozal, during his Presidency from 1989 until his death in 1993, had been bitten by the “neo-Ottoman” bug,17 while Demirel, though not famous for Pan-Turkist views, grew fond of rhapsodising about “the Turkic world from the Adriatic to the Great Wall of China” in the context of Turkey’s changing ambitions after the Soviet break-up. Turkish diplomats believed Demirel had picked up that slogan in the 1980s from former US National Security Advisor and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.18

A second international conference of Uyghur diaspora activists in 1999, this one held in Munich, retroactively declared the 1992 gathering to have been the First East Turke-stan World National Congress, and declared itself the second. It renamed the ETNC as the East Turkistan National Congress. Erkin Alptekin, once again, headed the revamped ETNC.

In 2004 the ETNC and Dolkin Isa’s WUYC merged, at yet another Munich conference, to establish the World Uyghur Congress (WUC). Erkin Alptekin was its inaugural president and Isa the general secretary. Reflecting post-9/11 (2001) sensitivity to the perils of pushing an agenda that could be seen as Islamist, the WUC from the outset focussed more on Uyghurs’ human rights and boosting Xinjiang’s autonomy within China than on independent statehood for “East Turkistan”. Some members of the ETNC, however, refused to drop their separatist demands; from among them arose the East Turkistan Government in Exile (ETGE).

The WUC and its many spinoffs became the primary source of anecdotal “evidence” of human rights abuses of Uyghurs. The major satellite organisations are the Uyghur American Association (UAA), founded at the First Uyghur American Congress in 1998, before the WUC; the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), founded in 2004 as a UAA project; and the Campaign for Uyghurs (CUF), headed by former UAA Vice President Rushan Abbas, who had previously worked at Radio Free Asia (founded on the Radio Liberty model in 1994) when it began Uyghur-language broadcasting in 1998.

The WUC, UAA, UHRP and CUF are the main recipients of Xinjiang-related funding from the NED (Part 7, “Project Democracy”), which has funded the WUC since its inception. In 2019 the WUC received the NED’s annual Democracy Award.

Erkin Alptekin’s successor as WUC president, in 2006, was Rebiya Kadeer. As a recent émigré from China, she was positioned to raise the profile of the Uyghur campaigns. Kadeer had taken advantage of China’s lessening restraints on private businesses in the 1980s to build a small laundry service into a department store, which she then parlayed—taking advantage of the lucrative cross-border trade with former Soviet republics after 1991—into a successful large trading company and became rich. As late as 1995 she was a delegate to top official institutions—the People’s Political Consultative Conference and the National People’s Congress. A second husband, Prof. Sidiq Rouzi, ended Kadeer’s privileged status. He emigrated to the United States in 1996 and worked as a journalist for Radio Free Asia and Voice of America. Kadeer was demoted in 1998 for refusing to denounce his activity. These were years in which serious terrorism was on the upswing in Xinjiang (Part 6, “Terror attacks in China”), making Beijing hyper-sensitive to every whiff of foreign interference. In 1999-2000 she was arrested, tried and sentenced to eight years for passing classified information to foreigners. The charges stemmed from her mailing of local Xinjiang newspaper clippings to Rouzi, at a time when such publications were listed as “internal” and not available for foreign subscription.19

Released in 2005, Kadeer moved to the United States, where she assumed the presidency of the WUC (2006-17) and the UAA (2006-11), and was President George W. Bush’s guest at the White House on several occasions. The NED newsletter Democracy of 24 July 2009 featured Kadeer as the “Mother of the Uyghurs” who “defends rights, deplores violence”.

Dolkun Isa, the WUC’s founding secretary, is its president today. In 2017, the same year as he succeeded Kadeer, he was also elected vice president of the UNPO. In 2016 Isa had received a human rights award from the Victims of Communism organisation.

In May 2009 the WUC, UNPO and NED co-hosted a conference in Washington on “East Turkestan: 60 Years under Communist Chinese Rule”, with a “Uyghur leadership training seminar” attached to the main event. The WUC and UNPO had held similar seminars in Berlin and The Hague the year before, announced as instructing “present and future leaders of the Uyghur community” on “Self-Determination under International Law”.20 That Washington event was followed by the Third General Assembly of the WUC, held on US Capitol premises thanks to friendly members of Congress.

The ‘East Turkistan Government in Exile’

The Uyghur diaspora activists who wanted to campaign more explicitly for an independent “East Turkistan” than the WUC was planning to, made their organisational move a few months later in 2004. They established the East Turkistan Government in Exile (ETGE), at a conference in Washington, DC. The ETGE’s inaugural president was Ahmet Igamberdi, the Australia-based activist who in 1992 had founded the East Turkistan Australian Association (ETAA) and had been a prominent figure at the Istanbul congress that year. The “prime minister” was one Anwar (sometimes “Enver”) Yusuf Turani, head of the non-profit East Turkistan National Freedom Centre (ETNFC) in Washington, which he had established in 1995. Ismael Cengiz, another ETGE leader, boasted in a 2009 interview that the famous Uyghur-Turkish Gen. Bekin had participated in a press conference to celebrate and support the new organisation.

Turani declared his hope “that the United States of America will recognise the just cause of freedom and independence of millions of East Turkistanis”.21 A US State Department spokesman answered a question about the ETGE on 22 November 2004: “The US Government does not recognise any East Turkestan government-in-exile, nor do we provide support for any such entity.” Turani himself claimed, in a 1999 interview, that his ETNFC had received financial support from wealthy patrons in Saudi Arabia.22

The flamboyant Turani currently claims to have been the first Uyghur granted political asylum in the USA, in 1988, although earlier accounts on his own website said that he came to the USA as a student after years of travelling among Uyghur diaspora relatives and other hosts in Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, the Soviet Union, Romania, Bulgaria and other countries, with a brief return to Xinjiang in 1986.

In 1999 Turani represented the ETNFC at a meeting with President Bill Clinton, to advocate for “freedom and independence of Eastern Turkistan”, claiming to speak on behalf of “more than 25 million Eastern Turkestanis”. In 1998 Turani visited Taiwan, accompanied by Erkin Alptekin and Tibetan and Inner Mongolian separatist leaders. They met then-President Chen Shui-bian, as well as Taiwan independence advocates.

The ETGE began regular street actions for publicity, like Turani’s 1996 speech in front of United Nations headquarters in New York, after which he cut a star out of the Chinese flag as a symbolic gesture of his “nation’s yearning to liberate themselves from Chinese occupation”.

The ETGE project has been especially prone to internecine fights and fragmentation, highlighted by an “impeachment” of Turani in 2006, though he persists in operating as the ETGE. There appear to be four ETGEs at present, of which Turani’s high-profile website and media appearances are one of the most visible, while the people who impeached him retain Igamberdi’s imprimatur as the main ETGE. It enjoys various institutional support in Washington.

Mutual accusations of being “Chinese agents” or terrorist-connected are routine among these groups (the main ETGE has banned Turani for being “connected to the jihadist Turkistan Islamic Party”), but they also overlap frequently. As of 2018, Turani’s daughter Aydin Anwar, who is “foreign minister” of his ETGE, was also a “media and press relations officer” for the East Turkistan National Awakening Movement (ETNAM), founded and headed by the current ETGE’s “prime minister”, Salih Hudayar. Anwar and Hudayar appeared together at rallies in December 2018, and ETNAM thanked her in January 2020 for acting in solidarity through her Save Uyghur Campaign.

In 2019 the ETGE intensified its activity, elevating a new generation of the Uyghur diaspora. Hudayar, then 27, was elected “prime minister”. Born in a family that fled Xinjiang in 2000 after accusations of “Islamic extremism”, he grew up in Oklahoma and served in the National Guard.

Before and after assuming leadership of the ETGE, Hudayar has promoted Uyghurs as an asset for the American military. In 2017 he said they could be used “to preserve US interests in Central Asia and the Asia-Pacific in the long run”, just as the Kurds have been exploited in the Middle East (his comparison). In 2019 Hudayar found hosts eager to give him a platform at the freshly minted, war-mongering Committee on the Present Danger-China (CPDC),23 where he spoke on 9 April. Frank Gaffney, who had chaired the CPDC’s inaugural conference two weeks earlier, invited Hudayar to speak about China’s alleged persecution of Uyghur and other Turkic peoples the next month at an event hosted by Save the Persecuted Christians—quite an irony, considering that Gaffney is a long-established rabid anti-Islam propagandist and his Centre for Security Policy (CSP) has received large contributions from Robert Mercer, the hedge-fund billionaire who heavily funds the white-supremacist alt-right movement.

The advisory team of Hudayar’s ETNAM includes other “war party” luminaries, such as Muslim Republican activist Zuhdi Jasser, a person highly praised by CPDC participant and former CIA Director James Woolsey and honoured by Gaffney’s CSP. Another ETNAM advisor is Dru Gladney, a China hawk who participated in Graham Fuller’s Xinjiang Project back in 1998-2003 (Part 3).

‘Peaceable’ groups whitewash terrorism

The WUC and its spinoffs maintain a pacific façade, opposing terrorism, but frequently whitewash or apologise for it. The ETGE, which though explicitly for breaking Xinjiang away from China also proclaims a “peaceful struggle for independence”, has an even dodgier track record, replete with threats of violence. ETGE co-founder Turani’s current website displays a 1947 “East Turkistan” separatist pamphlet, calling for the formation of “National Freedom Groups”, whose members pledged to achieve independence “by legal and illegal means … by words and by force of arms” and fight in the interests of people of all races “except the Chinese”. (The Chinese government at that time was not yet Communist.)

The EGTE’s 2004 constitution claimed that the “East Turkistan Republic” has been invaded by “Communist China”, and threatened punishment of “those who have collaborated with the invaders” (the wording has since been updated, but not changed in substance).

When US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a November 2020 parting shot at China, removed the official “terrorist organisation” designation from the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, which with its successor the Turkistan Islamic Party was responsible for major terrorism in the past two decades (Part 6, “Terror attacks in China”), the WUC and the ETGE cheered. WUC President Isa hailed the “historic significance” of Pompeo’s action. ETGE and ETNAM leader Hudayar, Voice of America reported, “said the State Department decision is equally important for Uighur Americans who have been afraid of using their preferred term ‘East Turkistan’ instead of Xinjiang lest they be associated with this ETIM group.”

There have been many incidents of individual “peaceful” Uyghur activists surfacing with explicit support for or collaboration with terrorists.

Mehmet Emin Hazret, another prominent figure at the 1992 Uyghur Congress in Istanbul, would go on to found the East Turkistan Liberation Organisation (ETLO), which in its active phase up to 2005 was designated a terrorist organisation not only by China, but also Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. In a 2003 interview with Radio Free Asia, Hazret stated that the ETLO would “inevitably” form a military wing to target the Chinese government.

In an undated video-recorded speech, posted to YouTube in 2019, the irrepressible original leader of the ETGE Anwar Yusuf Turani embraced Uyghur jihadists present in Idlib Province, Syria, as his own: “Ten thousand mujaheddin are gathered in Idlib”, he cried, “We brought them from Russia! Now, in Idlib, I can see in the field are my East Turkistani brothers... my soldiers…. They are much better fighters than the Chechens!”24

Serious incidents involving Thailand and Turkey have been linked with Seyit Tumturk, vice president of the WUC in 2006-16. Tumturk also founded the East Turkestan Culture and Solidarity Association (ETCSA), based in Turkey, in 1989. In 2015 the Thai government deported 109 illegal Uyghur immigrants to their home countries, including China. On the day of the deportation, 200 protesters bearing East Turkestan flags attacked the Thai consulate in Istanbul, smashing windows, in an action attributed to the ETCSA and Grey Wolves units. Tumturk was on the scene, telling Reuters on 9 July that they were protesting “Thailand’s and China’s human rights abuses”. A month later, according to the Thailand newspaper the Nation, the Bangkok police chief blamed a terrorist bombing that killed 20 people, most of them Chinese tourists, on “the same gang that attacked the Chinese consulate in Turkey”.

In March 2018 Tumturk declared that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs from Xinjiang were ready to enlist in the Turkish army and participate in Turkey’s invasion of Syria, if Turkish President Erdogan ordered them to.25

A Belt and Road to the future

National self-determination is one of the world’s most intractable problems. The United Nations Charter enshrines “friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”. Again and again, that principle has collided with fanatical ideologies like that of the influential Ukrainian fascist Dmytro Dontsov, who in his book Nationalism viewed “nations”—different ethnic groups—as biological species, such that “even two of them cannot be accommodated on one patch of ground under the Sun”. The legacy of the British-backed 19th-century Italian radical Giuseppe Mazzini’s national movements based on a “blood and soil” sense of identity (Part 4, “The Young Turks”), poisoned the minds of generations after him.

If the territorial claims of every identifiable ethnic group were drawn on a map, they would overlap as in the classic case of Greater Bulgaria, Greater Serbia, Greater Croatia, etc. in the Balkan Peninsula, with the result being war. Hence nations have agreed to respect post-World War II borders, even if they originated from unjust geopolitics, like the Anglo-French carve-up of the Middle East in 1916. The prospect of changing borders has occasioned great hypocrisy: for Anglo-American geopoliticians, for example, the secession of Kosovo from Serbia in 1991 could be approved, but Crimea’s declaration of independence from Ukraine and adherence to the Russian Federation in 2014 could not.

The history of large, multi-ethnic countries like the United States, the Soviet Union, or Australia show that tensions within them are complicated by real ethnic or racial prejudices, which get aggravated in times of crisis.

The history of large, multi-ethnic countries like the United States, the Soviet Union, or Australia show that tensions within them are complicated by real ethnic or racial prejudices, which get aggravated in times of crisis.

Forty-seven ethnic groups live in Xinjiang. Violence by Uyghur terrorists was directed heavily not only against Han Chinese migrants to the region, but also against the Hui people, another Muslim minority.26 Memories are generations long, and many of the Hui people who as of ten years ago made up around 3 per cent of Xinjiang’s 25 million population fear the prospect of being ruled by the Uyghurs. Fierce fighting in the region during the 19th century involved Uyghur-Hui disputes, as well as clashes between different Naqshbandi Sufi brotherhoods. Furthermore, contrary to a racist Australian Uyghur leader who posted on Facebook this year that “the indigenous people of East Turkistan have called East Turkistan their home for over 10 thousand years [before] Evil China even existed”, there is not a strong tradition of nationhood in Xinjiang; a 2004 study found that fragmented “oasis identities”—loyalty to a much smaller home area within the region—were the most prevalent.27

Yet the problems of the Uyghur population of Xinjiang can and must be solved. The principled basis for that is the 1648 Peace of Westphalia’s principle of acting “for the advantage of the other”, also reflected in 19th-century US President John Quincy Adams’s idea of a community of principle among nations. And a national idea can be based not on blood and soil, but on betterment of life for all—whether among nations, or within multi-ethnic ones. Chinese President Xi Jinping calls this a “win-win” approach.

What is not a solution is promotion from the outside of “national” consciousness by people who don’t really give two hoots about the population of the target area, but only want to exploit them for their own geopolitical and economic aims. Many members of the Eurasian diasporas came through the tumult of the 20th century with deep wounds, whether that be the experience of Australian Uyghur leader Ahmet Igamberdi, who spent six years at forced labour and 10 years in prison at the height of Maoist repressions in China, or the psychological damage obvious in Uzbek émigré Ruzi Nazar, who ten years after the Nuremberg Trials of the Nazis still found it appropriate to advertise his rank in the Nazis’ Turkestan Legion as a reputation-boosting element of his biography (Part 7). The diaspora has been cruelly exploited as well.

Anglo-American geopolitician and father of the neocons Bernard Lewis (Part 2) argued in an influential 1976 article for Commentary, “The Return of Islam”, that the western, Westphalian concept of a nation-state did not apply in Islam, because “Islam from the lifetime of its founder was the state, and the identity of religion and government is indelibly stamped” in the minds of the faithful. With that, Lewis was justifying his own hostility towards the legacy of Kemal Ataturk’s statecraft in Turkey, and his preference for a world of clashing non-nations that could be dominated by Anglo-American power centres.

Bernard Lewis’s way leads to permanent war. Under circumstances where the whole world is threatened with descent into a new dark age, yet China has been its sole engine of economic growth in the past decade and a half, while cultivating scientific optimism in its education policies and a commitment to promoting classical culture, a strategic posture that exploits the Uyghurs of Xinjiang for attacking China is nothing short of insane.

Was Beijing’s tough program for stopping terrorism perfect? Of course not. Even people well-disposed towards China criticise the treatment of Uyghurs after the Urumqi ethnic riots of 2009, comparing it to the ethnic profiling of people of Middle Eastern origin by US law enforcement after the 9/11 attacks. A Russian Sinologist, one of the first to argue that Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road policy is positive for Russia, explains: “Beijing’s policy in Xinjiang has more than one side to it, as we say. The excessive harshness towards Muslims is a fact, which has become particularly evident in very recent years. But it has an explanation, and I believe that is China’s overall mobilisation in the face of the Cold War with America that has started.”

Alongside Beijing’s anti-poverty programs, Belt and Road infrastructure-building is transforming life in Xinjiang for the better, but the Uyghur diaspora and “East Turkistan” organisations consistently condemn it as a mechanism of “occupation”.

As for the alleged defenders of human rights, it should be clear that one does not help the Uyghur people by attacking China.

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. Brian Glynn Williams, “On the Trail of the ‘Lions of Islam’: Foreign Fighters in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 1980-2010”, Orbis, Spring 2011.

3. “Asil Nadir Said Trading in Russian Uranium”, Aydinlik, 25 May 1993, translated by the Joint Publications Research Service.

4. Discussion of Fethullah Gulen and his Hizmet movement is beyond the scope of this article. A widely circulated analysis of radical Turkish nationalism and Islamist organisations holds that because former CIA official Graham E. Fuller (the Turcologist and Xinjiang expert) and former Ambassador Morton Abramowitz intervened to help Gulen obtain permanent residency in the United States, he and his movement should be understood purely as CIA assets. This is an oversimplification. Gulen’s influence since the 1960s on the desecularisation of Turkish society, clearing the way for Islamists to enter politics, has deeper roots—in the Nurcu tendency that stemmed from the Naqshbandi Order of Sufism (Islamic mysticism). Svante Cornell of the Johns Hopkins Central Asia-Caucasus Institute (CACI), Fuller’s publisher, analysed in a 2015 article “The Naqshbandi-Khalidi Order and Political Islam in Turkey”, how Gulen and most of the modern Turkish politicians mentioned in our articles arose from various Naqshbandi sub-orders. Despite Gulen’s role in his rise to power, current President Erdogan ultimately declared him a “terrorist” and blames much that goes wrong in Turkey on Gulen. Enver Altayli was arrested in 2016, charged with being a Gulenist.

5. “Russia’s North Caucasus republics: flashpoint for world war”, EIR, 10 Sept. 1999.

6. Joseph Brewda, “The neo-Ottoman trap for Turkey”, EIR, 12 Apr. 1996.

7. J. Todd Reed, Diana Raschke, The ETIM: China’s Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat (Praeger, 2010).

8. Joseph Brewda, “Pan-Turks target China’s Xinjiang”, EIR, 12 Apr. 1996.

9. “Uyghur Leader Dead at 85”, Radio Free Asia, 18 Feb. 2010.

10. Soner Yalcin, Erbakan (Kirmizi Kedi Yayinevi, 2012).

11. Note 8.

12. Ajit Singh, “Inside the World Uyghur Congress: The US-backed right-wing regime-change network seeking the ‘fall of China’”, The Grayzone (thegrayzone.com), 5 Mar. 2020.

14. Yitzhak Shichor, “Changing the Guard at the World Uyghur Congress”, Jamestown Foundation China Brief, 19 Dec. 2006.

15. Yitzhak Shichor, “Nuisance Value: Uyghur activism in Germany and Beijing–Berlin Relations”, Journal of Contemporary China, July 2013.

16. Yitzhak Shichor, Ethno-Diplomacy: The Uyghur Hitch in Sino-Turkish Relations, East-West Centre, 2009.

17. Ozgur Tufekci, “Turkish Eurasianism: Roots and Discourses”, in Eurasian Politics and Society: Issues and Challenges (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017).

18. Guven Sak, “From the Adriatic Sea to the Great Wall of China”, Hurriyet (hurriyetdailynews.com), 12 Aug. 2017.

20. “UNPO & WUC Spearheading Uyghur Leadership Training Seminar”, UNPO (unpo.org), 7 Apr. 2008.

21. J. Todd Reed, Diana Raschke, The ETIM: China’s Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat (Praeger, 2010).

22. S. Frederick Starr, ed., Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland (Routledge: 2004).

23. “Neocons declare war on China”, AAS, 3 Apr. 2019; “Anti-China crazies rampage on Capitol Hill and Wall Street”, AAS, 15 May 2019.

24. Dogu Turkistan Bulteni Haber Ajansi YouTube channel, translated from Turkish for AAS.

25. Abdullah Bozkurt (@abdbozkurt), Twitter, 11 Mar. 2018.

26. Isabelle Cote, “The enemies within: targeting Han Chinese and Hui minorities in Xinjiang”, Asian Ethnicity, 2015.

27. Note 22, article by J. Rudelson.