Xinjiang: China’s western frontier in the heart of Eurasia (Part 7)

By Melissa Harrison and Rachel Douglas

Parts 1 – 6 of this series appeared in the AAS of 18 November, 2 and 9 December 2020; 20 January, 3 and 17 February 2021. References to those articles are given in parentheses in this one.

China moves to stop terrorism

The terrorist attacks in Xinjiang, especially in 1997-2014, were deadly serious (Part 6, section “Terror attacks in China”). The Chinese government estimated in 2019 that more than 1,000 people had been killed by “East Turkistan”-related groups during the previous three decades. The Global Terrorism Database tally for that time period is approximately the same.1 Moreover, with a 2013 suicide car-bomb attack in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, for which the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) claimed responsibility, and the deaths of 33 people in the Kunming Railway Station stabbings of March 2014, Uyghur or “East Turkistan” separatist terrorism was no longer confined within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Chinese government response to the attacks had been a series of “Strike Hard” campaigns, aimed against “religious extremist forces”, “hardcore ethnic separatists”, and “violent terrorists”. There were widespread arrests and trials, prison terms handed down, and executions of terrorist leaders like those convicted of planning the Tiananmen car attack. At the same time, the leaders in Beijing evidently hoped that economic improvements under China’s Western Development guidelines, issued in 1999, would dampen unrest in Xinjiang.

When Xi Jinping came to power in 2012-13, it was already clear that these measures, even the significant investment of the Western Development program, were insufficient for ending the attacks in and from Xinjiang. The crescendo of terrorist acts up through 2014, as well as a different type of disturbance, the Han vs Uyghur ethnic clash that killed 184 people in Xinjiang’s capital city Urumqi in 2009, made it clear that economic development would not deter the instigators.

The new approach adopted under Xi should be contrasted to the so-called Global War on Terror, launched by the US Administration of President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, joined and supplemented by the Tony Blair and subsequent UK governments. Those regime-change efforts, such as in Iraq, Libya and Syria, and aerial bombardment campaigns have destroyed entire nations and fostered the emergence of more terrorists than existed before.

The new Chinese programs were designed to provide participants with job skills and employment opportunities, because poverty is recognised as a risk factor for radicalisation. “The development process was accelerated”, Schiller Institute analyst Mike Billington summarised in a 2020 article, “while the young people who were being subjected to Wahhabi indoctrination [Part 5, “Wahhabite education, jihadist training”] were brought into education centres, to provide vocational training, civics classes in Chinese law, improvement in the national language where needed, and religious education led by Islamic scholars. They were detained for an average of eight months. As of [December] 2019, all those detained have ‘graduated’, and the camps are now being transformed into public education facilities. There has not been a terrorist incident in China for the past three years. The Chinese didn’t bomb anybody. They arrested and incarcerated the actual terrorists, and they educated the rest of the population, succeeding in ending the terrorist threat within China.”2

In July 2019 an open letter issued by 37 UN member countries, influential Muslim-majority nations among them, supported Beijing’s “counter-terrorism and deradicalisation measures in Xinjiang” undertaken in the face of “the grave challenge of terrorism and extremism”. Responding to a complaint earlier that month by a UK- and USA-led group based on unsubstantiated characterisations of the Chinese measures, the governments demanded an end to the “practice of politicising human rights issues”.3

Eyewitnesses have described dramatic improvements in life in Xinjiang in the past decade, including a reduction of the fear of terrorism. Such reports will not be detailed in this article, but are well worth reading or watching, instead of accepting the mainstream media’s depiction of the region as a gigantic network of concentration camps.4

Despite the calming of the situation in Xinjiang, China still has reason for concern, as scenarios for Xinjiang-born terrorists to return home should signal (Part 6, “‘Foreign fighters’ from Xinjiang”). The American authors of a 2017 report for the Netherlands-based International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) observed that returning Uyghur Islamist veterans of the Syrian civil war “could be envisioned as shock troops” in a “simmering insurgency” in Xinjiang. They cited remarks by Chinese Maj. Gen. Jin Yinan, a national security and crisis management expert who today is a professor at China’s National Defence University, as evidence of Beijing’s awareness of this danger already in 2012; Jin warned that the TIP had joined the Syrian conflict not only to raise TIP’s international profile, but also “to gain operational experience in order to return to China and breathe new life into the insurgency back home.”5

Intelligence agencies manipulate diasporas

The American, British and allied geopolitical strategists who are bent on conflict with China, and their helpers in the media, seized on China’s counterterror efforts, which involved increased surveillance and security measures, to drive a narrative of indiscriminate oppression of Xinjiang’s Uyghur Muslim population. Even as the situation within Xinjiang calmed down and living standards began to rise, the “East Turkistan” issue was exploited more and more loudly.

Disinformation about Xinjiang is ever more extravagant, as the AAS and others have documented.6 Most recently Gareth Porter and Max Blumenthal, writing on the Grayzone website, dissected the work of anti-China zealot Adrian Zenz, who testified several times before the US Congress in 2018-19 during the run-up to passage of the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020, authorising sanctions against individual Chinese leaders accused of human rights violations. They found “flagrant data abuse, fraudulent claims, cherry-picking of source material, and propagandistic misrepresentations”.7

The same Anglo-American institutions that are leading the anti-China campaign, based on false accounts of repressions in Xinjiang, weaponised “human rights” issues long ago, for regime-change goals. The leading ones are Amnesty International, founded in the UK in 1961; Human Rights Watch, created in 1978 to support dissidents in the Soviet Union; and the US quasi-governmental National Endowment for Democracy, the flagship of funding and support for colour revolutions abroad.8

In a pattern carried forward from Cold War times, for Xinjiang-related propaganda these agencies utilise a support base within the Uyghur diaspora. The aim is not only to destabilise or even fragment a given country, but also to set “thought rules” for public opinion and political circles elsewhere—for example, in the USA or Australia.

One of the deadliest examples of this dynamic is Ukraine, a case not only parallel to that of Uyghur émigrés after World War II, but intertwined with it. When the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, millions of Ukrainian citizens—ethnic Ukrainians, Russians, and those of mixed or other ethnicity—advocated preserving close, cooperative relations with post-Soviet Russia. The dominant belief in official Washington, however, was that no true Ukrainian patriot would have that attitude. That myth stemmed from the radical ideology of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), founded in 1929 in Vienna with a base in Ukraine’s far western Galicia region as an insurgency against Polish rule (Galicia had been under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was assigned to Poland at the end of World War I). The OUN’s organisers held that Ukraine must become ethnically pure and that war against not only Poland, but ultimately Russia was inevitable. OUN leaders Stefan Bandera and Yaroslav Stetsko allied with Hitler in 1941, and near the end of World War II their Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), even as its Nazi erstwhile allies faced defeat, slaughtered tens of thousands of Jews and Poles in the name of ethnic cleansing.

Bandera remained a hero for many post-war Ukrainian émigrés to the USA and Canada. A cohort of Ukrainian diaspora members, sometimes two or three generations removed from immigration, came to hold influential posts in Washington, from which they preached the Banderite hard line of hostility towards Russia. They helped resuscitate the Bandera cult in Ukraine in the 1990s; it then formed the leadership of the 2013-14 US-backed coup against the country’s elected President. In the years that followed, Banderite activists and Ukrainian media under their influence have inculcated in an entire new generation the notion that to be a patriot of Ukraine, one must hate Russia.

Even American academic S. Frederick Starr and career Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer Graham Fuller, in their 2003 pamphlet The Xinjiang Problem,9 which projected worsening difficulties for China in the region, acknowledged that only a small minority of the Xinjiang Muslim population is pro-separatist. Furthermore, some of the other ethnic groups, like Kazakhs and Hui Muslims (native speakers of Chinese) fear Uyghur domination as much or more than rule from Beijing. Starr and Fuller estimated that separatists were “probably a distant third” behind “assimilationists” desiring to blend fully into Han Chinese culture and “autonomists” seeking more power within Xinjiang, but their evaluation didn’t stop the build-up of separatist campaigning within the Uyghur diaspora under the flag of “East Turkistan”. One result is the creation of a false impression among the uninformed public abroad that the population of Xinjiang, or at least a majority of the Uyghurs, are yearning to set up a separate state.

During the Cold War, political groups of émigrés from the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and Central Asia were labelled representatives of “captive nations”. Lobby groups such as the National Captive Nations Committee (in the USA) gained inordinate influence over politicians and the public. Some of their leaders were people who had collaborated with the Nazi armies invading the Soviet Union in 1941, either guided by their own racist, “blood and soil” ideologies or in search of escape from the brutality of Soviet policies of the 1930s, while others had suffered under Communist regimes and fled from native areas ravaged by the two World Wars.

Anglo-American strategists who anticipated fighting against their World War II ally the Soviet Union in the not too distant future sought to co-opt Nazi and fascist networks after the war. There was a paramilitary side to these intelligence-agency recruitment programs, as seen in Operation Gladio in Italy (Part 4, “The ‘Gladio’ template”) or British MI6’s backing of the OUN in subversive activity in Ukraine well beyond the end of the western Ukraine civil war between Soviet authorities and the remnants of the UPA in 1954.

The CIA’s Captive Nations

There was also a “civilian” side to CIA and MI6 network-building among ex-Nazis and their allies, which fed into covert operations in South America, the Middle East, and Europe, as well as affecting public opinion in the UK and the USA. For example, US Army Counterintelligence attempted in 1952 to block entry into the USA by Gen. Mykola Lebed, the OUN’s wartime security police chief, terming him “a well-known sadist and collaborator of the Germans”, but was overridden by CIA Director Allen Dulles on grounds that Lebed was of “inestimable value to this Agency in its operations”.10 The CIA went on to establish and fund the Prolog Research Corporation in New York City as Lebed’s base of operations, for intelligence-gathering and the distribution of nationalist and other literature inside the USSR. Prolog lasted until 1990, and supplied personnel who headed the Ukrainian section of Munich-based, CIA-funded Radio Liberty, broadcasting into the Soviet Union, in 1978-2003.

For Central Asia and, eventually, Xinjiang, one of the most important post-war CIA Captive Nations recruits was Ruzi Nazar, an Uzbek born in the Soviet Union in 1917 in a family with roots in the Central Asian Khanate of Kokand (17th-18th centuries).11 Conscripted into the Red Army (Soviet armed forces) in World War II, he was wounded, escaped in Ukraine, and joined the German forces. Nazar became an organiser of the Nazis’ Turkestan Legion (Part 4, “Central Asia between the wars”), which was deployed in northern Italy. He was on assignment in Germany when the war ended, but avoided the fate of many Turkestan Legion veterans—being handed over to the Soviets—and gradually began to offer his services to the Americans.

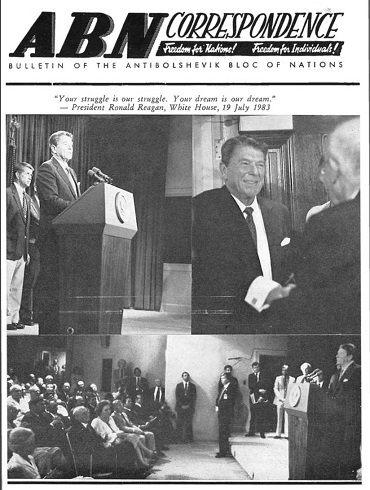

In 1948 the Truman Administration secretly initiated a program of covert operations against the Soviet Union. Plans were made for starting up Radio Free Europe (broadcasting to Eastern Europe) and Radio Liberty (to the USSR)—together, the RFE/RL complex. Inaugural CIA Director Allen Dulles coordinated establishment of the Free Europe Committee and the American Committee for Liberation from Bolshevism. A group of non-Russian émigrés from the Soviet Union refused to join in Russian émigré-dominated umbrella groups in Europe, which would not endorse the future independence of their native areas from Russia. Already in 1946 Stetsko, who as Prime Minister of a self-proclaimed Ukrainian state in 1941 had pledged to “work closely with the National-Socialist Greater Germany, under the leadership of its leader Adolf Hitler, which is forming a new order in Europe and the world”,12 revived the Committee of Subjugated Nations his OUN had run for the Nazis13, as a new Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) in Munich for non-Russian émigré activists. Initially backed by British MI614 and subsequently by the Americans, the ABN was soon joined by the head of the Azerbaijani National Committee and by Ruzi Nazar.

Asia against Russia and China.

Nazar was sought out in Munich and recruited to the CIA in 1951 by Archibald Bulloch (“Archie”) Roosevelt Jr, a grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt and now an officer of the CIA with particular interest in the Middle East and Central Asia. Archie Roosevelt describes in his memoirs, arguing with more Europe-oriented American officials that the United States should do more against the Soviet Union in Central Asia. At the very outset of the Cold War, three decades before Zbigniew Brzezinski would launch massive support for mujaheddin fighters in Afghanistan (Part 2, “Operation Cyclone—Afghan Mujaheddin”), Archie envisioned the strategy of undermining the USSR on its southern perimeter. In a chapter of his memoirs titled “Turan”, referring to the idea of uniting all the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, Roosevelt lamented that American policy-makers had failed to exploit “the subject races of Russia’s Asian empire [who] have continued to languish without any encouragement from us.”15

Roosevelt had already conducted semi-covert reconnaissance in Central Asia right after the war, entering through Xinjiang when the Soviets would not allow him access through Moscow. He convinced Nazar to cross the Atlantic, setting him up in a position at Columbia University in New York City, from where he would provide Central Asia analysis for the CIA. Nazar moonlighted as an analyst and scriptwriter for the Uzbek-language broadcast service of Voice of America.

In 1955 the Asian-African Conference of independent, newly decolonialised nations, not attached to either the Soviet or the Anglo-American-NATO bloc, took place in Indonesia, going down in history as the Bandung Conference. It laid the foundations for what would soon become the Non-Aligned Movement, led by Presidents Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, and India’s PM Jawaharlal Nehru. Ruzi Nazar, with covert backing from his CIA employers, wangled an invitation to attend as an observer from “Turkestan” (a country that did not exist). His goal was to push the “non-aligned” countries to denounce the Soviet Union and China as colonial powers. Nazar gave a press conference on the sidelines of the conference, billing himself as a former officer of the (Nazi) Turkestan Legion. At the last moment, he was joined by one Seyit Shamil, who arrived from Turkey representing anti-Soviet people from Russia’s North Caucasus.

Shamil had hoped that accompanying him to Bandung would be Isa Yusuf Alptekin, a Uyghur politician who had fled Xinjiang upon the Communist victory in 1949 and lived in Turkey (Part 4, “Post-Soviet Pan-Turk revival”). Alptekin could not travel closer to Bandung than Karachi, Pakistan, being unable to obtain an Indonesian visa. On his return trip, Ruzi Nazar stopped off in Karachi for talks with Alptekin, whom he urged to ally with Tibetans against the Chinese central government.

Alptekin began to identify with the international “captive nations” network. In 1969 he wrote an effusive letter to thank then-President Richard Nixon for continuing to celebrate Captive Nations Week in the USA, and to request the inclusion of “East Turkestan”.16

Back in the USA in 1956, Nazar made many contacts among Central Asian émigrés and Turks, including Col. Alparslan Turkes (Part 4, “Alparslan Turkes and the Grey Wolves”), then serving as Turkish General Staff liaison to the NATO Standing Group in Washington. Nazar would continue his friendship with Turkes during his (Nazar’s) 1959-71 posting in Ankara under diplomatic cover. During that time Turkes was a leader of the 1960 military coup in Turkey, and in the second half of that decade founded the ultra-nationalist National Movement Party (MHP) and its Grey Wolves terrorist arm—both patronised by Turkes’s colleagues in the military intelligence agency MIT. Turkes had introduced Nazar to Fuat Dogu, the future head of MIT, already in the USA.

Nazar also maintained close ties with Central Asian staffers at Radio Liberty in Munich and its associated Munich Institute for the Study of the USSR. Isa Alptekin’s son, Erkin Alptekin, would work at RFE/RL in 1971-95.

In 1961, right after the coup, Turkes launched a think tank called the Institute for Research on Turkish Culture (known by its Turkish acronym TKAE), roughly modelled on the CIA’s Munich Institute. Enver Altayli, an ex-MIT officer who is the biographer of Nazar, asserts that TKAE was funded for years by MIT, to implement Fuat Dogu’s scheme to weaken the Soviet Union—“What Turkey could do was to aggravate the nationalities problem.” The historian of TKAE agrees with Altayli that this idea may have come largely from Nazar, for “Nazar was of the opinion that the Soviet Union, despite its ostensible strength, had a soft belly, and that was the nationalities question.”17

Altayli reports that after his Turkey posting, Nazar became friends with Zbigniew Brzezinski and collaborated with him on The Soviet System and Democratic Society: A Comparative Encyclopedia (published in German, 1972). This was five years before Brzezinski would enter government and begin to carry out the Arc of Crisis policy (Part 2).

Project Democracy

In 1975 a US Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, named the Church Committee after its chairman, brought to light CIA involvement in assassinations of foreign leaders and other secret activity. An array of CIA covert operations were halted. In their place came a reorganisation, begun by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger during the Nixon and Ford Administrations (1969-75), in which traditional functions of intelligence agencies were replaced with operations centred in the National Security Council (NSC) (like the “Iran-Contra” scandal of the next decade) or other government departments. Under the Jimmy Carter Administration, with Brzezinski assuming Kissinger’s job at the NSC, these were cloaked as promoting “democracy” worldwide. Support for democracy—often measured by such criteria as economic deregulation and extreme free-market programs, which ravage the populations that are supposedly being democratised—became an axiom of US foreign policy.

The new orientation was formalised in 1983 during the Reagan Administration, with the inauguration of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and its two affiliated think tanks, one for each of the major US political parties: the International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute. Chartered as a quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation (QUANGO), the NED is funded by an annual grant from the US Congress—ranging US$170-180 million in recent years—and distributes money via its own grants to foreign activist groups and NGOs. It functions in parallel with the US Agency for International Development (USAID), a two-decades-older organisation for dispensing foreign aid, which itself also has “democracy offices” as part of its overseas missions. Additional funding to the USAID’s “democracy” programs and the State Department’s own Human Rights Democracy Fund is upwards of US$200 million annually.

Allen Weinstein, the American academic who co-founded the NED, declared in September 1991, “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA”. He argued that interference in other countries was more effective if done in the open.18 In a 2006 report on negative reactions to its meddling around the world, the NED denied that “democracy assistance” was equivalent to “regime change”, but insisted that democracy—defined as they see fit—“has acquired the status of the only broadly legitimate form of government”.19

Project Democracy, as the 1970s-80s policy shift became known, co-opted personnel from the Captive Nations networks. At a Washington conference of East European émigré groups in 1983, for example, participants were in a state of high excitement over large sums of money they anticipated coming to them from the new NED. In another 1983 incident, the aged Hitler-admirer Stetsko’s wheelchair was pushed into the vicinity of President Ronald Reagan at a White House Captive Nations Week function, just long enough for a photographer to snap a picture of their handshake for publication in the ABN bulletin.

The NED has funnelled US$8.76 million dollars since 2004 to activist groups campaigning against China’s policies in Xinjiang; all the publicly identified recipients are Uyghur diaspora groups. According to its published Asia Program and Annual Reports, the NED in 2010 prioritised “the rights of ethnic minorities” in projects focused on “Xinjiang/East Turkistan”. In December 2020, the NED’s Twitter account posted a map on which Xinjiang was labelled as “East Turkistan” and coloured with the East Turkistan flag.

Working side by side with the NED on Xinjiang-related propaganda are Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. Both have long records of selectively targeting their human rights campaigns in alignment with British and American foreign policy. Amnesty’s founder Peter Benenson, who had served in the UK’s Intelligence Corps in World War II, spoke of “its ultimate objectives … being those of Her Majesty’s Governments”.20 Amnesty’s covert support by the British Foreign Office was exposed in the 1960s. In 2014 more than 100 scholars, including two Nobel Peace Prize laureates and a UN Special Rapporteur on human rights, publicly called on Human Rights Watch to close the “revolving door” through which it shares personnel with the US Government.21

Amnesty International also has a record of dubious claims based on unverified reports. Most notorious is the “Kuwaiti babies” scandal during the First Gulf War (1990-91). Amnesty’s December 1990 false accusation, attributed to eyewitness doctors, that Iraqi soldiers had ripped hundreds of premature infants from their incubators, helped to motivate Operation Desert Storm, the move of US forces into Iraq in January 1991. Amnesty retracted the claims in April.

Amnesty has issued two reports on Xinjiang, one in September 2018 and a follow-up in February 2020. Both focus on allegations that ethnic minorities are being arbitrarily detained in the province. The first report was compiled from interviews with residents of Kazakhstan, who said they were unable to contact their relatives who live in Xinjiang. A Kazakh activist group named Atajurt, whose Xinjiang-born leader is known for fiery statements like “If my brother works for the Chinese, if my brother sells himself to the Chinese, I would kill him”, arranged the interviews. The author of the second report was Patrick Poon, Amnesty’s Hong Kong-based China researcher, based on mostly anonymous interviews and a questionnaire “circulated among a closed pool of trusted Uyghur contacts”.

A September 2018 Human Rights Watch report against China’s “campaign of repression” in Xinjiang likewise relied on interviews, arranged by the same Kazakhstan-based activists, with anonymous ethnic Kazakhs who had left Xinjiang.

The Henry Jackson Society, a London think tank named for the late American hawk Henry “Scoop” Jackson, has aggressively engaged on the Uyghur issue to bash China. (It was HJS President Brendan Simms who infamously hailed the “success” of the 2011 US/NATO intervention in Libya, saying: “Democracy can be dropped from 10,000 feet”.) The HJS has hosted several events discussing the Uyghurs, including a January 2019 meeting featuring Enver Tohti, who claimed to have been forced as a surgeon to perform organ-harvesting from Uyghur prisoners in China. His story was heavily publicised in the international media, but two months later Tohti admitted the claim was a hoax.

In Australia, the primary disseminator of reports and allegations of Chinese government human rights abuses against Uyghurs in Xinjiang is the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), a government-funded think tank which also gets funding from the US State Department, the UK government and NATO. We analysed the fraudulent arguments in ASPI’s March 2020 report, Uyghurs for Sale, in a previous article.22

Final instalment: The 'East Turkistan' narrative (conclusion)

Footnotes: (Click on footnote number to return to text)

1. The GTD, maintained by the National Consortium for the study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, University of Maryland, is online at www.start.umd.edu/gtd/. Its total of 978 deaths in terrorist incidents in China, 1990-2019, omits casualties in the Baren Riot of 1990 (Part 6), but includes some attacks that may not have been separatist-related, as well as incidents of clashes between ethnic groups.

2. Mike Billington, “British Creation and Control of Islamic Terror: Background to China’s Defeat of Terror in Xinjiang”, EIR, 10 Jan. 2020; “China Chooses Development and Education, Not War, to Combat Terrorism”, 9 Aug. 2019.

3. Richard Bardon, “Muslim countries reject claims of ‘cultural genocide’ against Xinjiang Uighurs”, AAS, 24 July 2019.

4. For example, “Is China committing genocide against Uyghur Muslims? A British-Aussie’s eyewitness report”, Citizens Insight (www.youtube.com/c/CitizensPartyAU/videos), 28 Oct. 2020, an interview with Jerry Grey, who lives in China and has bicycled through Xinjiang.

6. Richard Bardon, “Uighur ‘mass detention’ reports fabricated by US, British propagandists”, AAS, 26 Sept. 2018; “ASPI doubles down on Xinjiang ‘detention centre’ fakery”, AAS, 30 Sept. 2020.

7. Gareth Porter, Max Blumenthal, “US State Department accusation of China ‘genocide’ relied on data abuse and baseless claims by far-right ideologue”, thegrayzone.com, 18 Feb. 2021.

8. Rachel Douglas, “Destabilising Russia: The ‘Democracy’ Agenda of McFaul and His Oxford Masters”, EIR, 3 Feb. 2012, uncovers the late Gene Sharp’s US Defence Department-funded development of colour revolutions—allegedly non-violent projects which are a form of irregular warfare.

10. Richard Breitman, Norman J.W. Goda, Hitler’s Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, US Intelligence, and the Cold War (National Archives, 2012).

11. Enver Altayli, A Dark Path to Freedom: Ruzi Nazar, from the Red Army to the CIA (London: Hurst & Company, 2017).

12. “Ukraine: Violent Coup, Fascist Axioms, Neo-Nazis”", EIR, 16 May 2014.

13. Paul Rosenberg, “Seven Decades of Nazi Collaboration: America’s Dirty Little Ukraine Secret”, The Nation, 28 Mar. 2014.

14. Stephen Dorril, MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service (The Free Press, 2000).

15. Archie Roosevelt, For Lust of Knowing: Memoirs of an Intelligence Officer (Little. Brown, 1988).

16. Isa Yusuf Alptekin, “Memorandum sent to Richard Nixon, President of the United States of America”, 12 July 1969, on file at digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org.

17. Ilker Ayturk, “The Flagship Institute of Cold War Turcology”, European Journal of Turkish Studies, 2017.

18. David Ignatius, “Innocence abroad: The new world of spyless coups”, Washington Post, 22 Dec. 1991.

19. The Backlash Against Democracy Assistance (NED, 2006).

20. Tom Buchanan, “‘The Truth Will Set You Free’: The Making of Amnesty International”, Journal of Contemporary History, Oct. 2002.

21. “Debate: Is Human Rights Watch Too Close to US Gov’t to Criticise Its Foreign Policy?”, democracynow.org, 11 June 2014.

22. Melissa Harrison, “ASPI: forced labour hypocrites and academic fraudsters”, AAS, 14 Oct. 2020.