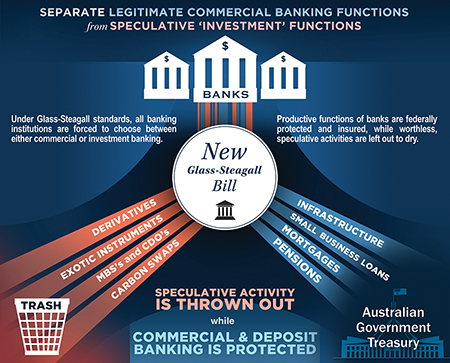

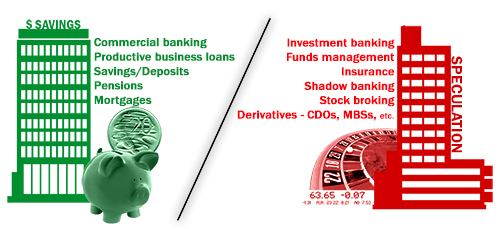

Australia must break up its banks, so that traditional commercial banking of taking deposits and making loans is kept separate from all other financial activities, including speculative, risky investment banking, as well as insurance, stock broking, financial advice, wealth management and superannuation.

This policy is based on the US Glass-Steagall Act (Banking Act of 1933), which successfully protected Americans from banking crises for nearly 70 years, until its fateful repeal in 1999 led to an explosion in financial speculation and the 2008 global financial crisis. The Citizens Party’s draft legislation, the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2019, was first introduced into Parliament in June 2018 by Bob Katter and then into the Senate in February 2019 by Pauline Hanson.

What is “Glass-Steagall”?

The original US Glass-Steagall Act (named for its co-sponsors, Senator Carter Glass and Representative Henry Steagall) was enacted in 1933 in response to the Great Depression, and protected the American banking system from systemic financial crises for the next 66 years until its ill-fated repeal in 1999. Specifically, under the Glass-Steagall Act, commercial banks which held deposits protected by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)—the savings accounts, chequing accounts, and business trading accounts—were forbidden from owning, or being owned by, Wall Street investment banks. It didn’t stop speculation, but it severely curtailed it, because it denied Wall Street investment banks any access to the enormous deposit base of the American people. It was when Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999, that Wall Street finally got access to the commercial banks and their deposits, and all forms of speculation expanded exponentially.

Although Australia never had formal Glass-Steagall legislation, we did maintain a highly regulated financial system to the same effect: protecting and fostering the physical economy. That system was destroyed by the waves of deregulation unleashed by the 1981 Campbell Report, which allowed the present concentration of the financial system in the “Big Four” TBTF banks plus Macquarie, and the mixing of normal commercial banking with speculation-ridden investment banking.

The Citizens Party (then CEC) drafted the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2018, which Bob Katter MP introduced in Parliament in June 2018 and again by Senator Pauline Hanson in February 2019. The bill adapts Glass-Steagall for the Australian banking system: it forbids the banks from engaging in investment-banking activities such as trading in securities and derivatives, and ends the vertical integration that has enabled the banks to fleece their customers. It brings the bank regulator APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) under strict Parliamentary control, and stops APRA from coordinating with the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) to bail in deposits. While Glass-Steagall doesn’t immediately solve all of the problems in the banking system—for instance, the $1.7 trillion in largely unpayable mortgage debt—the structural separation Glass-Steagall imposes will provide a stable framework within which such problems can be addressed, through the indispensable institution of a new national bank.

Read Why Australia urgently needs a Glass-Steagall banking separation

Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2019

Need for this bill

It is obvious that Australia’s Big Four banks and Macquarie are devoted solely to their own usurious profits at the expense of the population as a whole. We must therefore break up these “vertically integrated”, self-centred and crime-ridden behemoths and return to the sort of tightly regulated banking system which existed under our original Commonwealth Bank, which was dedicated to the Common Good. Towards that end, the Citizens Party (then Citizens Electoral Council) drafted the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2018 which was first tabled in the House of Representatives by Bob Katter on 25 June 2018 and more recently tabled in the Senate by Pauline Hanson on 12 February 2019.

General outline

Given the onrushing global financial crisis, this present legislation is proposed for immediate implementation within the current Australian banking structures and institutions. It mandates the separation of normal retail commercial banking activities involving the holding of deposits, from wholesale and investment banking, which are rife with risky activities; and, whilst guaranteeing deposits in commercial banks, removes explicit and implicit government guarantees for any such activities outside of the core business of normal commercial banking. It also proposes to provide strict accountability and Parliamentary oversight of the activities of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) as the banking regulator, which since its establishment in 1998 has not only overseen, but actually fostered the growth of Australia’s present, speculation-centred, crime-ridden financial system.

Australia’s present financial system, particularly those aspects introduced during the waves of deregulation that followed from the 1981 Campbell Report, which allowed its present concentration in the “Big Four” too-big-to-fail (TBTF) banks plus Macquarie and the mixing of normal commercial banking with speculation-ridden investment banking and other financial services within the same institutions, is recognised to be a disaster which fosters financial speculation at the expense of the real, physical economy and the majority of the population. Moreover, the City of London/Wall Street-centred global financial system, of which Australia’s banks are an integral part, itself now faces a new collapse.

Background

The Australian and international media have featured repeated warnings from present and former officials of the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the US Federal Reserve System, as well as former leading bankers and other prominent commentators, that the world is headed towards a far greater financial crash than that of 2007-08.

This inevitable prospect has been caused by the waves of “free market reforms” enacted since the breakup of the fixed-exchange-rate Bretton Woods system in 1971. These reforms include privatisation, deregulation, manipulations of fluctuations in currency exchange rates, and the creation of over US$1 quadrillion in speculative instruments known as derivatives, such as the mortgage-backed securities that provoked the 2007-08 crash and are once again soaring in number.

This new global bubble in the trans-Atlantic system, including Australia, is not simply a bubble in one part of “the market”, such as mortgages. Rather, the relentless “quantitative easing” by central banks, totalling an estimated minimum of US$12 trillion since 2008, has created an “everything bubble”, including car loans, student loans, corporate loans, the US stock market which has exceeded US$30 trillion, the bitcoin bubble, and others.

This post-2008 system is centred upon a handful of TBTF banks, typified by those in the City of London, on Wall Street, and in the European Union, and Australia’s Big Four plus Macquarie, all of which have looted the population in favour of speculative profits.

The creation of this TBTF system was enabled by the 1986 “Big Bang” deregulation of the City of London and the repeal of the US Glass-Steagall Act in 1999.

From the time Glass-Steagall legislation was passed in 1933 until it was repealed in 1999, there had been no such systemic crisis in the US banking system.

Australia has never had Glass-Steagall-style banking separation, but the domestic banking system was not always exposed to the level of risk it is today, because until the 1980s a system of regulatory controls effectively implemented separation.

Australia’s Government-owned Commonwealth Bank was intended by its promoter King O’Malley to be a national bank, but, instead, a watered-down version was legislated in 1911. Nevertheless, it exercised a degree of control over the banking system, and in 1911-1959 the Commonwealth Bank strengthened the banking system, stopping runs on private banks: no Australian banks failed during the Great Depression, compared with the more than 4,000 American banks that permanently closed their doors between 1929 and the 1933 passage of the Glass-Steagall Act. Prior to the Commonwealth Bank, banking in Australia had been very volatile, 22 Australian banks having failed in the 1891-93 economic crisis.

Labor leaders John Curtin and Ben Chifley gave the Commonwealth Bank even greater powers over the private banks during and after WWII. The Commonwealth Bank regulated what the private banks could charge for loans and pay for deposits, and the extent, and nature, of bank lending, but this regulation did not prevent private banks from remaining profitable. Bank regulation was based on the principle of the common good: the financial system must serve the needs of the people. To do that, the banking system had to be structured to ensure that credit was available for the government to build infrastructure and invest in national economic development, and for essential primary and secondary industries, the productivity of which generated the tangible wealth that underpinned the living standard of the population. Banking controls minimised the ability of the private banks to speculate, and encouraged investments in the production of physical infrastructure, goods and essential services.

Chifley’s successor, Liberal Party Prime Minister Robert Menzies, stripped the Commonwealth Bank of its regulatory powers over the private banks in 1959, and vested those powers in a new central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia—the bankers’ bank.

The global financial system changed dramatically on 15 August 1971, when US President Richard Nixon ended the Bretton Woods system of fixing the US dollar to gold. This unleashed a global push for financial deregulation, masterminded by the powerful banking houses of the City of London. The post-1971 system constituted a new form of British imperialism—not territorial as of old, but as an “informal financial empire”, in the words of its own proponents.

In 1979 the Liberal Party established the Financial System Inquiry headed by Sir Keith Campbell. The resulting 1981 Campbell Report demanded the wholesale elimination of Australia’s regulated financial system, including the abolition of government controls over bank lending, by which the government had instructed the banks to give preference to farmers, small businesses, and home-buyers; the sale of all government-owned financial institutions that existed to provide cheaper finance to farms and small businesses, such as the Australian Industry Development Corporation, the Primary Industry Bank of Australia, the Commonwealth Development Bank, and the Housing Loans Insurance Corporation; the abolition of the “30/20 Rule” and other ratios that had obliged the savings banks, trading banks, life offices and superannuation funds to invest a fixed percentage of their assets in government bonds, thus providing security for the financial institution and ensuring the government could borrow readily; the removal of government controls over all interest rates charged by banks; the abolition of government controls over the amount of lending by banks; the lifting of all controls over capital flows in and out of Australia and the floating of the dollar; and the admission of foreign banks into Australia. Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser opposed many of these demands, so his government implemented only the recommended entry of foreign banks into Australia.

But the subsequent Hawke-Keating Labor Government initiated the 1983-1984 Vic Martin inquiry, which simply rubber-stamped the demands of the Campbell Report. Treasurer Paul Keating had already condemned the senior executives of Australia’s banks as smug fat cats, protected by regulation from real competition, and stripped away Australia’s banking regulations beginning with the December 1983 float of the Australian dollar.

Liberal Party Treasurer Peter Costello took the process still further by initiating the 1996 Wallis Inquiry, which demanded the removal of restrictions on mergers between the banks and big life insurance offices; stripped the Reserve Bank of its remaining powers to regulate the banks; and established a new, “independent” banking regulator—APRA. Costello publicly confirmed for the first time that there was no formal guarantee for bank deposits in Australia.

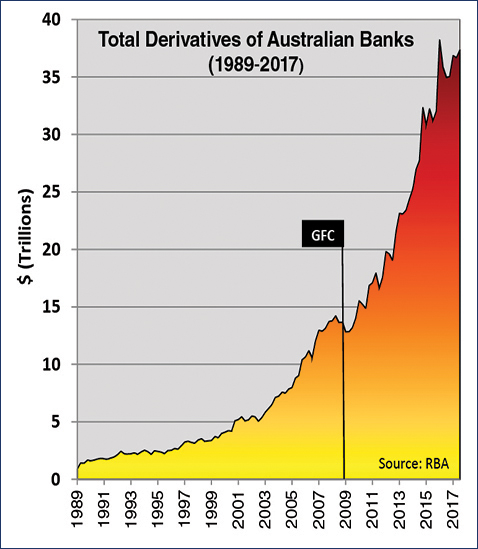

From these two periods of banking reform has emerged Australia’s highly concentrated, TBTF banking system, with its almost $38 trillion exposure to toxic derivatives and hundreds of billions of dollars of short-term debt. But even the architects of deregulation are well aware that they have exposed the Australian public to enormous risk. Interviewed in the 2008 book Unfinished Business: Paul Keating’s Interrupted Revolution, Keating admitted to author David Love a “minor” detail kept from the public in the 1980s—that at least two of Australia’s Big Four banks would have collapsed at that time, had the government not propped them up because they were already “too big to fail”. Reflecting the results effected by the Campbell Report, Keating recalled, “The old domestic banks went like charging bulls into credit expansion from 1985 on.... Eventually, they had us in a position where we dared not check them lest they failed. Westpac and the ANZ virtually did fail: the government and the Reserve Bank had to hold them together until they got back on their feet.”

The speculation became even worse following the 1998 establishment of APRA, which supervised the creation of today’s mortgage bubble—generally acknowledged as the first or second worst in the world—by rigging prudential regulation to favour speculation in mortgages, much of which was financed by overseas borrowing. Thus, in 2008 the Rudd government had to guarantee the banks’ huge foreign borrowings as well as their deposits; without these guarantees, they would have collapsed. All the while, the government was assuring the public that the banks were “sound”. Under the benevolent eye of APRA—which is funded by the banks themselves and, while formally responsible to Parliament, takes its direction from the Bank for International Settlements in Switzerland, which insists the government must not “interfere” with APRA’s operations—the Big Four’s holdings of mortgage-centred, ultra-risky derivatives have soared from $14 trillion in 2008 to over $37 trillion today. Australia’s TBTF banks now hold 60 per cent of their assets in mortgages, compared with 30 per cent in the USA and just over 20 per cent in London. This property bubble has been financed by massive foreign borrowing. And, contrary to the endlessly repeated mantra that Australia has the “safest financial system in the world”, its mortgage bubble is a mortal threat not only to Australia, but to the entire City of London/Wall Street-centred Western financial system, a reality reported in the 5 February 2018 Australian Financial Review article, “Australian banks may pose global systemic threat”.

Thanks to this relentless deregulatory process, initiated with the 1981 Campbell Report and supervised since 1998 by APRA, Australia’s “financial sector” now constitutes an astounding 9 per cent of Australia’s economy, as opposed to the City of London’s “mere” 7 per cent of the UK economy and Wall Street’s 6 per cent of the US economy. It has been created at the expense of our real physical economy, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which have been devastated, with family farms almost obliterated and our manufacturing sector at only 6 per cent of GDP—the lowest level in the Western world. Indeed, this is precisely what Paul Keating intended when he proclaimed in 1985 that Australia should be the “Wall Street of the South” and, in terms of industry, concentrate on its “long suit” of exporting primary products; in other words, that the proud Australia of the post-war years, with its vibrant new factories and family farm-centred agricultural sector, should devolve into a typical “Third World” economy under foreign imperialist rule.

This deregulation and privatisation process has enriched speculators and the TBTF banks at the expense of the general population, which suffers soaring prices for food, housing, energy and other basic necessities. Moreover, Australia’s TBTF banks have been repeatedly caught in criminal activity such as drug money laundering, terror financing, interest rate rigging, stealing from their depositors, and other crimes, committed during the period of APRA’s oversight of them since 1998. In short, Australian governments no longer control and direct the financial system, but now operate at the behest of the financial system.

Summary of legislation

The legislation:

- Prohibits banks from any affiliation with an entity that is not a bank. (Sections 7, 8, 9)

- Prohibits any entity that is not a bank to engage in the business of receiving deposits. (Section 10(1))

- Prohibits banks from investing in structured or synthetic products and products such as derivatives and speculative ventures. (Section 10(4))

- Limits the business of banking to retail banking and associated loans and activities. (Section 11)

- Brings the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (“APRA”), as the licensing and regulatory Authority, and its prudential standards and actions and decisions generally, under the oversight of Parliament. (Section 14)

- Limits the Financial Claims Scheme to deposits with banks whose activities do not include any prohibited activities. (Section 13)

Effect of legislation

The effect of the legislation will be:

- To re-establish public confidence in the banking system;

- To reduce risks to the Australian financial system by limiting the ability of banks to engage in activities other than socially valuable core banking activities;

- To limit conflicts of interest that arise from banks engaging in activities from which their profits are earned at the expense of their customers and the national interest;

- To remove explicit and implicit government guarantees for high-risk activities outside of the core business of banking;

- To regulate Australian banks and any foreign bank operating within Australia;

- To provide Parliamentary oversight of the activities of APRA as the banking regulator;

- To separate retail commercial banking activities involving the holding of deposits, from wholesale and investment banking involving risky activities.

Further financial system reforms

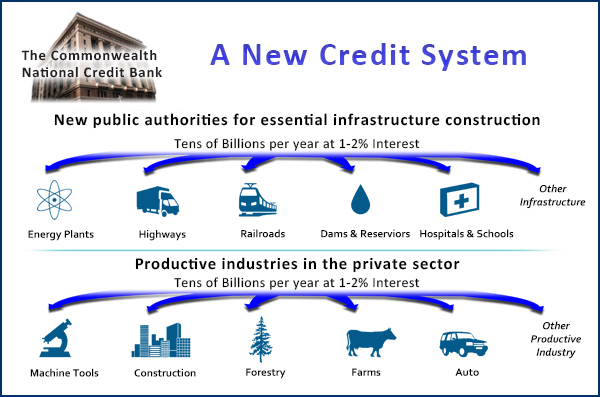

Such urgently required separation is merely the first step. The full reform of Australia’s banking system requires a more comprehensive package of legislation that overturns the current monetarist philosophies and policies and returns Australia to a public credit-based system implemented through a system of national banking. Such a system must be anchored upon the re-establishment of a new, government-owned and directed national bank to regulate Australia’s national credit, to provide such credit for urgently needed infrastructure projects, and to drive a renaissance of Australia’s agro-industrial, physical economy. Legislation for this new national bank is to be modelled principally upon our original Commonwealth Bank as it functioned under its founding director Sir Denison Miller from 1912 to 1920 (before private banking interests seized control of it), and the Australian banking system as it was regulated under Prime Minister John Curtin and Treasurer Ben Chifley and functioned so magnificently during World War II and even up until 1959 when the Reserve Bank was established. The new Commonwealth National Credit Bank would replace the Reserve Bank, and the new bank’s Reserve Division would be mandated to licence and regulate Australia’s private banks and foreign banks operating in Australia, as did the original Commonwealth Bank, thereby replacing APRA, which would be abolished. In the meantime, APRA must be placed under the strict supervision of Parliament, which is, in turn, responsible to the population as a whole.

The creation of a true national bank would restore to the Australian Parliament the Constitutional power to regulate Australia’s economy. It will act in Australia’s national interest, through ensuring an orderly flow of credit and currency to public infrastructure and utilities, and to private enterprise engaged in the production and transportation of tangible economic wealth, including manufacturing, agriculture, construction, and mining. Successive governments have been deficient in this regard by abrogating this power, relinquishing it to private banking interests operating in a regulatory framework run by APRA and ultimately directed by APRA’s masters in the Bank of England and the BoE-established, supranational Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland. Thus, foreign and Australian private banking interests have exercised arbitrary judgments on monetary policies, in violation of Australia’s national economic interest.

The new national bank would finance nationwide infrastructure projects in water, high-speed rail, and energy among other vital aspects of the economy, to act as science-drivers of real economic development, and to increase Australia’s physical-economic productivity and therefore the standard of living of all Australians.

Further legislation required

Separate legislation will be required for the regulation of credit unions, building societies, insurance companies and superannuation fund managers, to either supplement, qualify or replace the legislation at the state level that currently governs such institutions and persons.

US banking expert Nomi Prins on Glass-Steagall

Nomi Prins delivers remarks to the Schiller Institute’s 30th anniversary conference, discussing her latest book All The Presidents’ Bankers, which details the “historical alignment of the White House and Wall Street” from Teddy Roosevelt to Barack Obama.